Expert Review

5 Most Common Skin Diseases in Primary Care

Chapter 1: Urticaria

Guest Editors

Jaggi Rao, MD, FRCPC

Kaushik Venkatesh, BS

Question & Answer from an Allergist’s Perspective

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

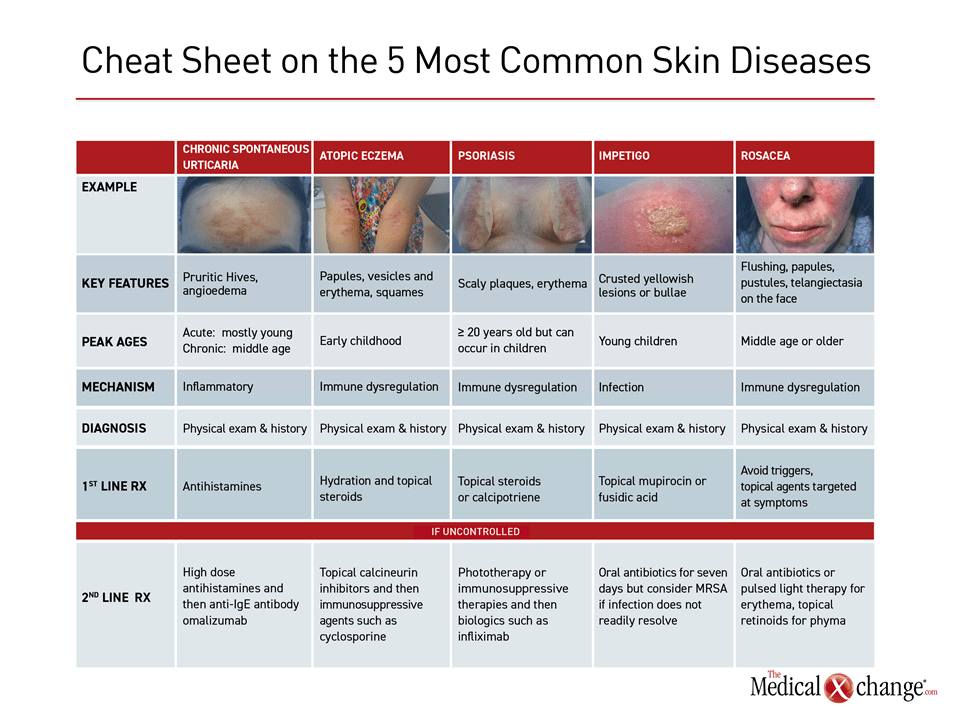

Urticaria is characterized by hives, which typically develop over a short period of time and are accompanied by pruritus. Angioedema, which can be painful, accompanies the wheals in approximately half of cases. Angioedema typically occurs in rich neurovascular areas such as fingers, lips, and around the eyes. The erythematous hives typically appear as raised pale often plaque-like lesions on an erythematous background. They can appear on essentially any part of the skin and in patients of any age.

The lifetime prevalence of all urticaria is 20%, but this skin disease is classified into two major types by duration. Chronic urticaria, which has a much lower prevalence and is more common in adults of middle age or older, refers to persistent lesions for periods of more than six weeks. Acute urticaria refers to a presentation of a shorter duration. Acute urticaria which denotes hives occurring for under 6 weeks may be triggered by medications, infections, insect stings, food allergies, and other acute factors. Chronic spontaneous urticaria is typically idiopathic without known or consistent triggers but can co-exist with inducible triggers such as physical triggers. For example, in physical pressure induced urticaria, it typically occurs in areas of increased pressure due to clothing.

Pathophysiology

Degranulation of mast cells in the skin is the primary driver of urticaria. Mast cells and basophils release histamine and other mediators, such as cytokines and lipid mediators, to induce an inflammatory reaction that underlies the characteristic rash and pruritus. Immunoglobulin E through the FcERI receptor is one mediator of activation and degranulation of mast cells, but non-IgE activation also commonly occurs to physical triggers, tachykinins, complements, toll like receptors, and autoimmune mechanisms.3 Angioedema accompanies the hives when degranulation includes mast cells deeper in the dermis. The inflammatory activity excites sensory nerves, promotes vasodilation, and increases the permeability of postcapillary venules.

For an eLearning program with Dr. Jaggi Rao on the impact to clinical practice, click here

On histology, wheals demonstrate an inflammatory perivascular infiltrate that might include neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, macrophages and T cells. Endothelial cell adhesion molecules, neuropeptides, and T cells are also often present. Although skin adjacent to lesions may also contain upregulation of cytokines, eosinophils, and adhesion molecules, urticaria is a condition localized to the skin without systemic involvement (Fig. 1). Rarely, urticaria may be a symptom of serious anaphylaxis or a major underlying disease.

Diagnosis

Neither acute nor chronic urticaria requires an extensive diagnostic workup. Rather, the diagnosis of urticaria is one of exclusion that is reached with history to rule out alternative pathologies, particularly systemic diseases.4 At initial examination, the history should document the time o0f onset as well as the location, severity, and impact of the symptoms. Other important aspects of history include potential environmental triggers, medication use such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications and allergies. A diagnosis of urticaria is appropriate in those with characteristic features and no systemic or vasculitic symptoms, such as fever, gastrointestinal complaints, arthralgias or myalgias. Extensive laboratory testing or biopsies in the absence of such symptoms are not recommended. Many dermatologic conditions can be confused with urticaria; it crucial to rule out anaphylaxis which has systemic consequences and involves other organ systems.2

For acute urticaria, there is a long list of potential triggers, including heat, cold, sun exposure, foods, alcohol, drugs, stress, pressure on the skin, and prescription drugs. Repeated episodes of urticaria that occur in a temporal relationship to triggers provide both a diagnosis and a potential strategy for removing the cause. Although the identification of triggers is helpful in the diagnosis of acute urticaria, urticaria remains idiopathic in more half of patients who meet the definition of chronic disease.

When chronic urticaria is idiopathic, which accounts for 80% to 90% of cases,1 an entity now commonly referred to as chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), autoantibodies for IgE can be commonly identified, but the absence of autoantibodies does not rule out CSU or guide therapy, so it is not considered a routine diagnostic procedure. Although the presence of angioedema should increase attention to potential drug triggers, such as antihypertensive medications, it does not necessarily justify biopsy or more extensive laboratory studies when symptoms remain localized to the skin.

Treatment

The single most important goal of treatment for urticaria, which imposes a large adverse impact on quality of life through its symptoms and appearance, is to improve quality of life. Urticaria poses a low risk of serious complications. In cases of acute urticaria, trigger avoidance may adequately address symptoms. In cases where avoidance is problematic, tolerance induction should be considered.

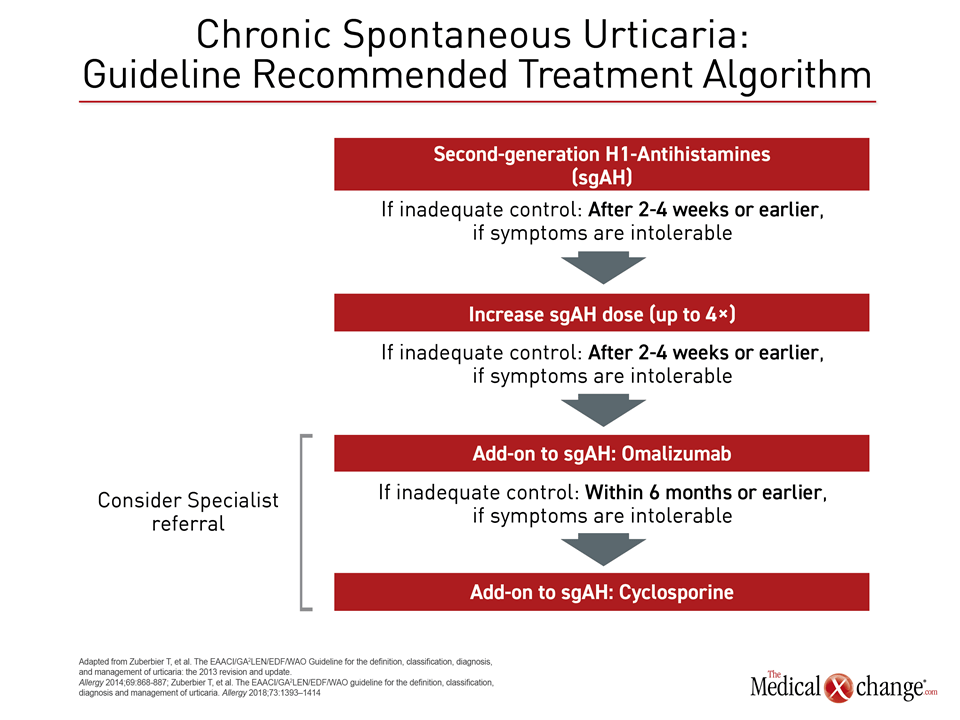

Second generation antihistamines represent the first-line of pharmacologic therapy for acute or chronic urticaria (Fig. 2). Recent guidelines specifically recommend avoiding first-line antihistamines due to their sedative effects and adverse impact on sleep.4 When selecting among agents, relative risk for drug-drug interactions should be considered for patients taking antibiotics or other drugs with a potential to compete on pathways of drug metabolism.

For acute urticaria, symptom control with antihistamines can be expected with a short course of therapy. H2 antihistamines such as cimetidine, famotidine, and ranitidine may be added if symptoms continue, and corticosteroids such as prednisone may be added for a three to ten days in severe cases.2 For chronic urticaria, recent guidelines recommend a stepwise care approach, moving from a conventional dose of a second-generation antihistamine as a first-line therapy to high doses of antihistamines as the next step when adequate symptoms control is not achieved. Escalations up to four times the conventional dose are recommended. With these two steps, more than 50% of patients can anticipate adequate symptom control.

For those still uncontrolled, the next step in treatment is to add anti-IgE antibody omalizumab to the antihistamines. The phase 3 trial found omalizumab resulted in a high degree of efficacy for the primary endpoint of pruritus control as well as for key secondary endpoints involving control of angioedema and resolution of lesions. The drug was well tolerated with low rates of serious adverse events.

In those who remain uncontrolled, alternative agents are appropriate, but cyclosporine is listed first among alternatives in the current guidelines, which delisted H2-receptor antagonists and leukotriene receptor antagonists due to the weak quality of available evidence. The guidelines do acknowledge corticosteroids as efficacious but conclude that cyclosporine has a better benefit-to-risk ratio despite the concern for potential side effects.

In an outline of therapies specifically for children, the guidelines reemphasized the importance of relying on second- rather than first-generation antihistamines due to a more favourable side effect profile. The authors further recommended second-generation antihistamines that have been tested in children. The agents on this list are cetirizine desloratadine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine, rupatadine, bilastine, and loratadine.

Summary

Urticaria is a common condition characterized by hives and itching and can be accompanied by angioedema. It is non-life-threatening with a low risk of significant complications, but it imposes a major adverse impact on quality of life. In the majority of cases, the diagnosis is easily reached by a careful history that rules out systemic involvement. Laboratory testing and biopsy are not routinely employed in patients without alarm features of symptoms that suggest an alternative diagnosis. Consistent with a pathophysiology that is characterized by mast cell degranulation and histamine release, antihistamines are the main stay of pharmacologic therapy. In those with chronic urticaria, which is typically spontaneous, additional steps may be required to achieve adequate symptom control. Initial workup and first-line therapies for urticaria are appropriate at the level of primary care. The simple goal is relief of symptoms in order to improve quality of life.

Urticaria: The Allergist’s Perspective:

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Internal Medicine

Toronto Allergy and Asthma Clinic

Toronto, Ontario

1. Should urticaria be considered an allergic or dermatologic disease?

Short answer is both. Urticaria can be a dermatologic manifestation of a type I Gell and Coombs hypersensitivity reaction, which defines an allergic process. However, the manifestations primarily by definition are occurring in the skin terminally differentiated mast cells which are distinct from GI mast cells and other visceral mast cells in the body. Due to the recent evolution of the understanding of CSU having an underlying type I or type II autoimmune mechanism (anti-IgG to FcERI or IgE vs an autologous allergen) it simply represents the degranulation of mast cells irrespective of the trigger. In fact, the most common form of chronic inducible urticaria (CINDU) is triggered through baroreceptors that sense pressure on the mast cell. While it shares some pathophysiology to atopic conditions such as atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis it is mediated by a different population of mast cells as mast cells are terminal organ differentiators. There is some recent thought that CSU really represents another type II inflammatory condition due to the prevalence of autoimmune mechanism as an etiology

2. When is it appropriate to refer a patient with urticaria to a specialist?

A specialist consult is not normally required either to make the diagnosis or to initiate treatment. Adequate symptom control can be achieved in the majority of cases with secondary antihistamines and trigger avoidance where found Contrary to popular misconception, CSU is not caused by food allergies or inhalant allergies. This risk of serious complications is low. A specialist consultation becomes appropriate when an adequate quality of life cannot be achieved with up titration of antihistamines to four times the dose. Anyone requiring omalizumab or cyclosporine should be referred to an experienced specialist familiar with biologics and or cytotoxic immunosuppressants that require monitoring.

3. If patients do not respond to first- or second-line treatment for urticaria, what is the most appropriate specialist referral, a dermatologist or an allergist?

In cases where the response to antihistamines is inadequate, the anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab has been shown to be effective. Although this drug is typically well tolerated, clinicians experienced with this agent, which requires in some cases reconstitution of the medication with subcutaneous dosing, might be more comfortable with administration. In patients who no response to high doses of antihistamines, a detailed workup for an alternative diagnosis might be appropriate. Either a dermatologist or an allergist are reasonable choices provided they are experienced with cytotoxic immunosuppressants that require monitoring for cyclosporine or have critical number of experience using biologics In addition, rarely a patient does not respond to omalizumab or cyclosporine and a specialist familiar with adjunct therapies is helpful.

Additional Slide

(Fig. 3)References

1. Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:1270-7.

2. Schaefer P. Acute and Chronic Urticaria: Evaluation and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2017;95:717-24.

3. Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:1527-34.

4. Jain S. Pathogenesis of chronic urticaria: an overview. Dermatol Res Pract 2014;2014:674709.

5. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy 2018;73:1393-414.