Expert Review

5 Most Common Skin Diseases in Primary Care

Chapter 2: Eczema

Guest Editors

Jaggi Rao, MD, FRCPC

Kaushik Venkatesh, BS

Question & Answer from an Allergist’s Perspective

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

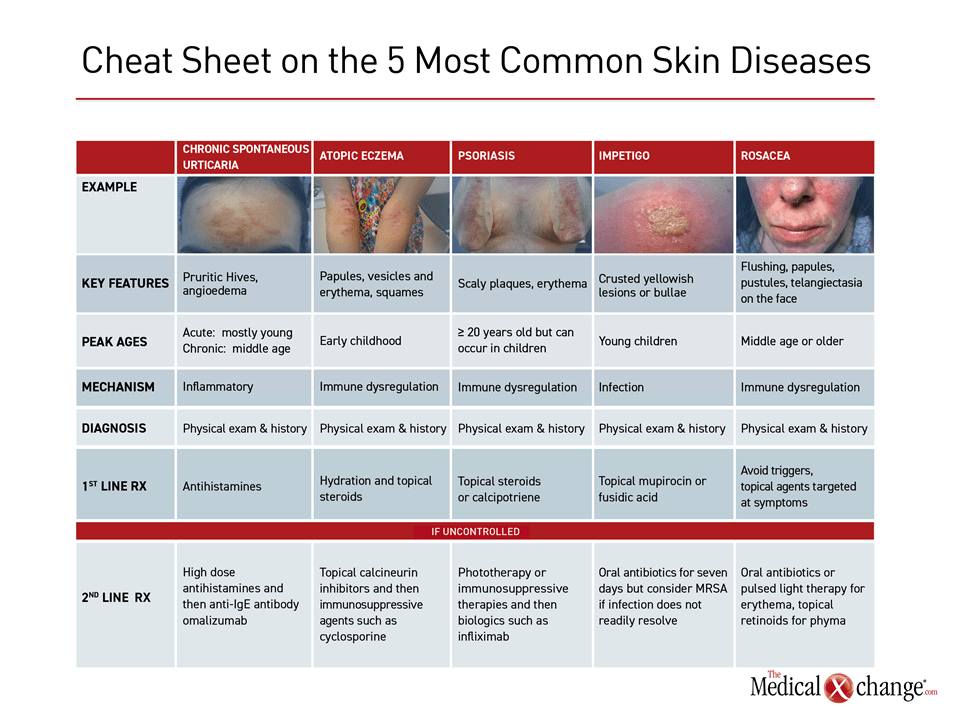

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is an inflammatory and pruritic condition of the skin with a variable presentation frequently involving some combination of vesicles, papules, and oedema. Guidelines differ on the necessity of a history of atopy as prerequisite for a diagnosis of eczema but agree that the diagnosis is made clinically. Most cases of eczema involve childhood onset with up to 60% of cases developing within the first year of life. In Canada, approximately 10% of children develop atopic dermatitis during childhood, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere. Adult cases are less common but not rare. In the event of childhood onset, spontaneous remissions prior to adolescence are observed in up to 70% of cases but can re-emerge in some patients.

Eczema, often first observed on the scalp, face, or flexure areas of the limbs, is characterized by a relapsing course. Most cases are of mild to moderate involvement, but approximately 10% are severe, involving frequent flares and an extensive lesion burden. Other atopic conditions, such as bronchial asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, are common in those who develop eczema at an early age. Although infection can complicate eczema, the largest burden of this condition is physical and psychological discomfort.

Pathophysiology

Immune dysregulation and defects in skin barrier function are both implicated in the pathogenesis of eczema, but this interaction is not completely understood. Although the concordance rate for atopic dermatitis among monozygotic twins is 77%, suggesting a high degree of heritability, studies of genetic variants suggest that environmental triggers may be important for disease development in at least some patients.7 Both immune dysregulation and disturbances in skin barrier function are implicated in disease expression, but it is unclear which comes first. On histopathology, eczematous skin includes a perivascular infiltrate of T cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and eosinophils, which might be a driver of disease or an immunologic response to a loss of the epidermal barrier function (Fig. 1).

Although IgE-mediated sensitization is a common feature of many patients with atopic dermatitis, this is not uniformly observed and it is uncommon in the early stages of disease.6,10 Overall, the factors involved in the pathogenesis of eczema are likely to include genetic susceptibility, environmental allergens, infectious agents, and resident skin bacteria, initiating and then driving inflammation. Pruritic-driven scratching of the skin is also a factor in formation of lesion inflammatory activity. It has been argued that non-atopic eczema might be a useful term to distinguish non-IgE-mediated disease from a true atopic form,11 but others have rejected this as an unhelpful division that does not account for transient IgE upregulation.7 Although anti- inflammatory therapy is a cornerstone of eczema treatment, treatments designed to augment epidermal barrier function through topical moisturization also have a potential role in mitigating and attenuating disease processes.

Diagnosis

There is no biomarker or single test to establish a diagnosis of eczema.12 Rather, the diagnosis is made on the basis of multiple criteria. The set of Hanifin and Rajka criteria, published in 1980, remain widely cited.13 These include pruritic chronic or relapsing dermatitis and a family history of atopy without other known aetiology. Accompanying characteristics, such as erythema, cheilitis, recurrent conjunctivitis, and frequent cutaneous infections may be helpful in supporting a diagnosis of eczema. There is general agreement that face and neck involvement is more common in infants and young children while lesions on flexural surfaces of the extremities and on the hands and feet are more common in adolescents and adults.14

History or presentation plays a critical role when differentiating eczema from other types of dermatitis or other skin conditions. In the absence of a family or personal history of atopy, scabies, impetigo, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and lichen simplex are among alternative diagnoses to consider.15 However, these differ in general appearance and are not typically expressed in the same areas as eczema. Diagnostic work-ups utilize patient history, skin and blood tests, and challenge tests to investigate exacerbating factors as well as to prescribe treatment regimens and avoidance recommendations.

Treatment

Guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD),2 the joint task force (JTF) of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology and American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology,3 and a panel of European organizations12 identify non-pharmacologic therapies as the first-line intervention for mild eczema. This basic therapy should comprise optimal skin care, addressing the skin barrier dysfunction and avoiding triggering factors. This includes bathing to remove irritants and bacteria followed by moisturizers to maintain skin hydration. Hydrophilic ointments without fragrance and preservatives are preferred in AAD and JTF guidelines. Although food allergies are more common in patients with eczema, food allergies are not the driver of eczema. Moreover, although dust mite and mould sensitization is common and dust mites have protease activity, it is a minor contributor to eczema flares.

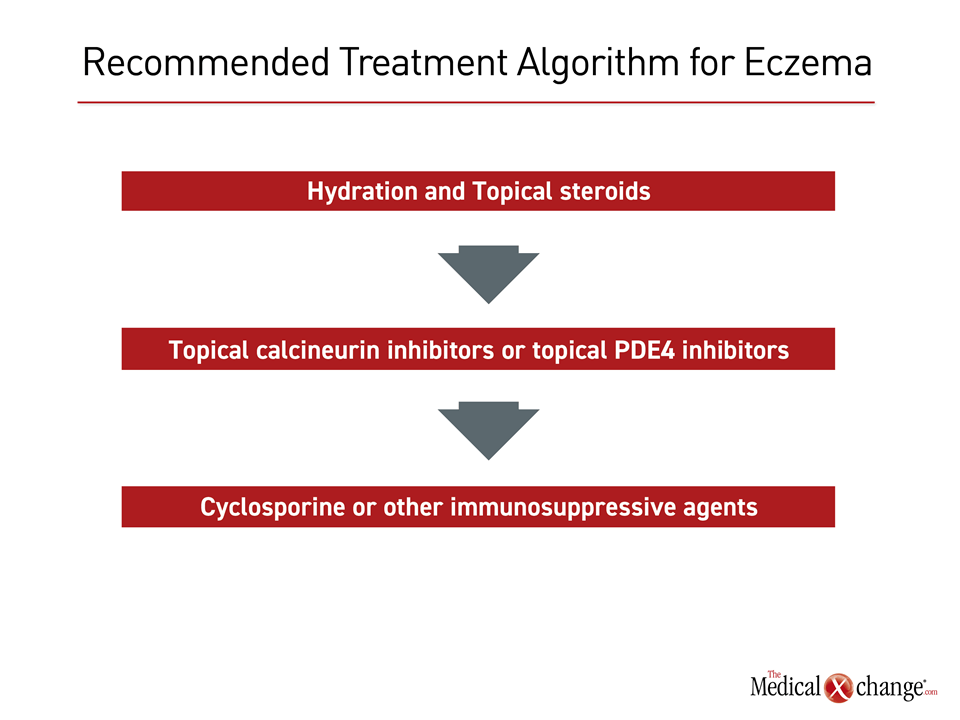

In the European guidelines, treatment recommendations are listed separately for adults and children, but are compatible. For both, topical class II steroids are considered first-line for those with mild disease inadequately controlled with non-pharmacologic interventions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are listed as an alternative. Wet wrap therapy and ultraviolet light were identified as adjunctive therapies to topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors for those with moderate to severe disease. In severe disease, systemic immunosuppression with such therapies as cyclosporine A, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil are recommended in children and are off label in adults. In adults, dupilumab, an anti-IL-4 and IL-13 monoclonal antibody, is currently the only approved systemic therapy specifically for eczema (Fig. 2).

The AAD and JTF guidelines discuss the same pharmacologic interventions in the same order. Relative to the European guidelines, which offer limited advice on how to identify provocation factors, the JTF and AAD guidelines encourage control of atopic-related triggers, such as food and contact allergens. The JTF guidelines, in particular, endorse steps such as avoiding clothing with irritating fabrics and washing clothes with non-allergenic soaps.

Even though all of the guidelines acknowledge that randomized trials of eczema treatments are limited, recognizing that current guidelines are largely guided by expert opinion, the treatment strategies are largely compatible among the published guidelines. For optimal disease management, consistent medical supervision, education of the patient or the person who provides care to the patient, and a strong psychological support system are needed.16

Summary

Eczema is a common relapsing pruritic dermatitis associated with atopy. Face and neck involvement is more common in infants and young children while involvement of the flexures, hands, and feet is more common in adolescents and adults. There is no definitive diagnostic test, but an adequate history and examination is sufficient to reach a diagnosis of eczema in most cases. By reducing skin damage from scratching, moisturizers are an important, non-pharmacological first step to control of lesions. Topical steroids are regarded as a first-line pharmacologic therapy. Eczema resolves before adolescence in the majority of patients who develop eczema in early childhood.

Eczema: The Allergist’s Perspective:

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Internal Medicine

Toronto Allergy and Asthma Clinic

Toronto, Ontario

1. What is the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis?

Eczema, which is interchangeable with AD, is a type II inflammatory condition and as such other atopic comorbidities are often observed in patients such as allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, and asthma. The underlying cascade of release of inflammatory mediators is a similar but not identical process related to Gell and Coombs type I hypersensitivity. Patients with AD are at increased risk of having contact dermatitis which is a type IV Gell and Coombs hypersensitivity. Although commonly mistakenly identified as “allergens” these are in fact technically antigens that trigger a T cell initiated response with different effectors than mast cells. IL-33 (found mainly in the skin on keratinocytes and not in other organs), IL-4, and IL 13 are important in the start and propagation of the itch, scratch, and lichenification cycle. Contact dermatitis testing requires patch testing and not skin prick testing, as it is not an IgE mediated reaction.

2. When is it appropriate to refer a patient with eczema to a specialist?

Patients with eczema or other atopic diseases can typically be diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and history. There is an extensive differential but careful examination for typical patterns and signs such as lichenification and xerosis in areas typical for AD points one in the right direction. Control of mild involvement is often achieved with topical treatments, but a specialist consultation becomes appropriate if the symptoms do not respond to first-line therapies. Both a dermatologist and clinical immunologist and allergist are typically familiar with non-steroidal topical therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors and PDE inhibitors.

3. If patients do not respond to first- or second-line treatment for eczema, what is the most appropriate specialist referral, a dermatologist or an allergist?

Primary care physicians who have limited experience with administration of potent systemic immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine and topical and systemic calcineurin inhibitors might prefer to refer patients with atopic dermatitis who do not respond to topical agents. Likewise, not all specialists in dermatology or allergy are familiar or experienced with the use of biologics such as dupilumab and a referral should be made in severe atopic dermatitis. For a patient with atopic comorbid conditions, including those affecting the respiratory tract, an allergist might be a better first choice.

Additional Slide

(Fig. 3)References

1. Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, Borok J, Udkoff J, Boguniewicz M. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: A comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:S49-S57.

2. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:338-51.

3. Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:295-9 e1-27.

4. Barbeau M, Bpharm HL. Burden of Atopic dermatitis in Canada. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:31-6.

5. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:209-13.

6. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:925-31.

7. Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1483-94.

8. McAlister RO, Tofte SJ, Doyle JJ, Jackson A, Hanifin JM. Patient and physician perspectives vary on atopic dermatitis. Cutis 2002;69:461-6.

9. Lowe AJ, Carlin JB, Bennett CM, et al. Do boys do the atopic march while girls dawdle? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:1190-5.

10. Novak N, Bieber T. Allergic and nonallergic forms of atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:252-62.

11. Brown S, Reynolds NJ. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. BMJ 2006;332:584-8.

12. Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32:657-82.

13. Rothe MJ, Grant-Kels JM. Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. Lancet 1996;348:769-70.

14. Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, et al. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994;131:383-96.

15. Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2018;14:52.

16. Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:152-69.

Chapter 2: Eczema

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is an inflammatory and pruritic condition of the skin with a variable presentation frequently involving some combination of vesicles, papules, and oedema. Guidelines differ on the necessity of a history of atopy as prerequisite for a diagnosis of eczema but agree that the diagnosis is made clinically. Most cases of eczema involve childhood onset with up to 60% of cases developing within the first year of life. In Canada, approximately 10% of children develop atopic dermatitis during childhood, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere. Adult cases are less common but not rare. In the event of childhood onset, spontaneous remissions prior to adolescence are observed in up to 70% of cases but can re-emerge in some patients.

Eczema, often first observed on the scalp, face, or flexure areas of the limbs, is characterized by a relapsing course. Most cases are of mild to moderate involvement, but approximately 10% are severe, involving frequent flares and an extensive lesion burden. Other atopic conditions, such as bronchial asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, are common in those who develop eczema at an early age. Although infection can complicate eczema, the largest burden of this condition is physical and psychological discomfort.

Show review