Expert Review

5 Most Common Skin Diseases in Primary Care

Chapter 3: Psoriasis

Guest Editors

Jaggi Rao, MD, FRCPC

Kaushik Venkatesh, BS

Question & Answer from an Allergist’s Perspective

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

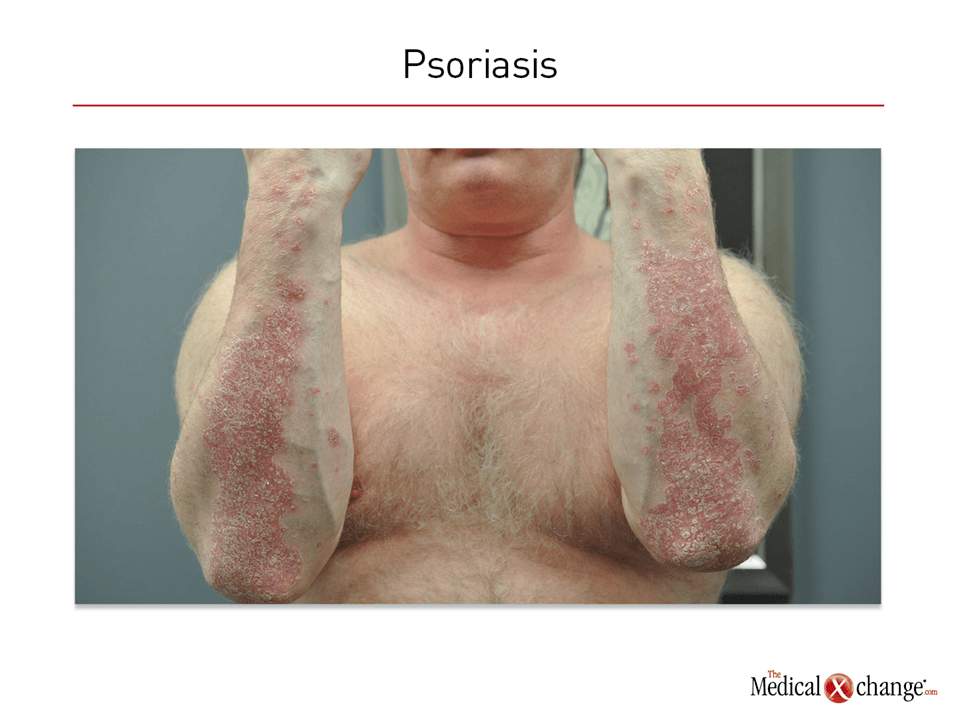

Psoriasis is a chronic disease characterized by well-demarcated scaly plaques driven by a hyperproliferative epidermis. Although it most commonly involves the scalp, elbows, and knees, it can develop on most skin surfaces, including the palms, soles, and genitalia. Nail involvement is observed in nearly 50% of patients. Total body involvement provides an objective measure of psoriasis severity, but it may not reflect the disease burden for patients self-conscious about lesions or who have persistent pruritus. Common phenotypes include guttate, pustular, annular, erythematous, and palmoplantar forms. The adverse impact of psoriasis on quality of life, including diminished self-esteem, is a well-documented feature.

In Canada, the estimated prevalence of psoriasis is 1.7%, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere. Psoriasis is considered an autoimmune inflammatory process. The most common age of onset is between the ages of 20 and 30 years, although psoriasis can develop in children. Up to 30% of patients also develop inflammation of the joints. Although many of the anti-inflammatory medications effective for psoriasis also reduce disease activity in the joints, psoriatic arthritis is typically managed separately. A variety of disease phenotypes classified by appearance or predominant site of involvement have been described, but psoriasis vulgaris is the most common form of the skin disease.

Pathophysiology

Psoriasis is driven by a dysregulated immune system. Based on the frequency with which psoriasis occurs in related individuals, genetic susceptibility appears to be important. Association studies suggest that the PSORS1 gene may account for up to half of psoriasis heritability, although other genes have been implicated in linkage studies.1 Genetic heterogeneity among psoriasis subtypes supports the involvement of multiple pathways. For many patients, this might involve a disturbance in the sentinel function of dendritic cells, altering the innate immune defense mechanisms and inducing proliferation of T cells and proinflammatory cytokines.7

On histopathology, the macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells are prominently represented in the dermis. The erythematous appearance is attributed to capillaries reaching close to the surface of the skin due to a thinned epithelium (Fig. 1). The efficacy of anti-inflammatory drugs including biologics targeted at inflammatory cytokines has provided an important demonstration that an upregulated immune system drives disease and an important target of therapy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is made on the basis of clinical examination and history. This should include a characterization of lesion distribution and appearance during an examination that includes the scalp and nails. Although there is no definitive test or biomarker for psoriasis, suspicion should increase in those with a family history of psoriasis. The Auspitz sign, which is pinpoint bleeding when psoriatic scales are removed, and the Koebner phenomenon, which is the appearance of new lesions at sites of trauma, may provide additional confidence in the diagnosis but have limited independent sensitivity.8 From the Canadian Psoriasis Guidelines Committee, disease severity is judged to be mild, moderate, or severe based on body surface area coverage and effect on quality of life. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index similarly measures the disease severity using body surface area affected, erythema, induration, and scaling.4

There are different clinical types of psoriasis, but the most common is chronic plaque psoriasis, which affects 80% to 90% of psoriasis patients.4 The differential diagnosis of psoriasis includes seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, and mycosis fungoides.9 The risk of confusion with other skin diseases is low when psoriasis includes involvement of the trunk, but skin biopsies are useful when features overlap with other conditions. Diagnosis may be particularly challenging in cases when psoriatic lesions are confined to the scalp or hands. KOH examination is useful for ruling out dermatophyte infection masquerading as psoriasis in these locations.

Treatment

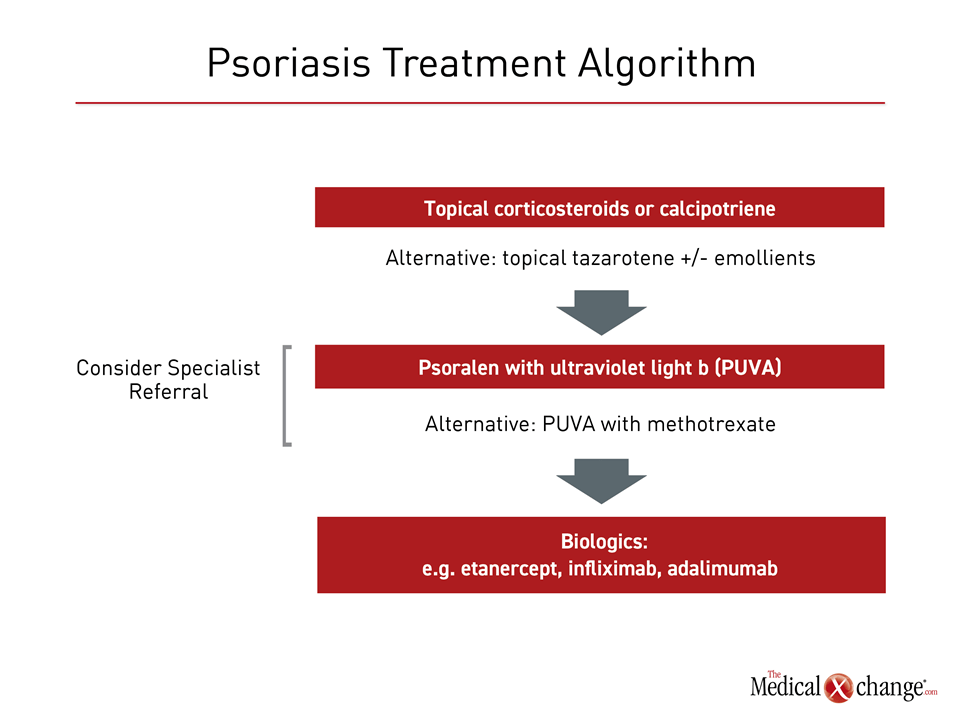

Although there is no cure for psoriasis, there are several effective treatment options. In patients with mild psoriasis, topical corticosteroids, topical calcipotriene, or calcipotriol-steroid combination products may be sufficient as a first-line therapy to reduce lesion burden and pruritus. Topical tazarotene, a retinoid, has also demonstrated efficacy in mild disease.10 Emollients might be useful as adjunctive therapy. For more severe disease, systemic therapies or ultraviolet (UV) light are appropriate. Of systemic therapies, once-weekly methotrexate, alone or combined with UVB or photochemotherapy (PUVA), has been in use for decades. However, concern about side effects has reduced the clinical application of other once commonly used immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine (Fig. 2).

Biologics, such as etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, are now commonly introduced relatively early in the course in patients with moderate to severe disease because of their relative efficacy in lesion clearing. However, referral to specialists is appropriate. Biologics, which are expensive, pose significant clinical risks, including increased propensity for malignancy. Despite these risks, biologics are perceived to have a favourable risk-to-benefit ratio when lesions are inadequately controlled with alternative treatment strategies. Non-biologics such as acitetrin and apremilast have also been used, but are not considered the mainstream treatment from the current literature.4

Overall, the goal of therapy in psoriasis is to control disease activity to improve quality of life. Even severe psoriasis is rarely life threatening, but the physical distress induced by lesions is complicated by the psychological burden of visible lesions, which can cause patients to limit activities of daily living. These can include constraints on social interaction and employment.

Summary

Psoriasis is a chronic, multisystem, autoimmune disorder characterized by pruritic plaques. Nail and scalp involvement are common. Apart from skin and joint involvement, the disease is associated with various psychiatrics and medical comorbidities. Topical therapies are a first-line therapy in patients with mild disease, particularly when control of pruritus can limit skin damage from excoriation. Many of the most effective therapies, including ultraviolet light and immunosuppressants, are associated with significant risks, including malignancy, when utilized chronically. Primary caregivers are uniquely positioned to offer timely diagnosis and treatment of mild to moderate cases. In cases of extensive involvement on visible skin surfaces, patients should participate in a detailed discussion with specialists of the risk-to-benefit ratio regarding available therapies.

Psoriasis: The Allergist’s Perspective:

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Internal Medicine

Toronto Allergy and Asthma Clinic

Toronto, Ontario

1. Should psoriasis be considered an allergic or dermatologic disease?

Psoriasis is a type I autoimmune inflammatory disorder affecting the skin with systemic symptoms that involve joints or other organs (rarely the lungs). No strong associations have been made between development of psoriatic lesions and hypersensitivity reactions. In some patients with psoriasis they do have some type II atopic conditions and it has been found that there is a regulatory T cell (Treg) that may be the culprit.

2. When is it appropriate to refer a patient with psoriasis to a specialist?

Except in mild cases, suspected psoriasis should be referred to a dermatologist for evaluation and the initiation of treatment. Psoriasis is a chronic and often challenging condition for which a comprehensive treatment plan may be important for an optimal outcome. An experienced dermatologist will likely screen for systemic involvement.

3. If patients do not respond to first- or second-line treatment for psoriasis, what is the most appropriate specialist referral, a dermatologist or an allergist?

Psoriasis that is inadequately controlled with topical therapies and appropriate skin care can be challenging. Second- and third-line therapies, such as PUVA and biologics, are associated with significant risks that are best administered by physicians familiar with the benefit-to-risk ratio of these treatments. In most cases, this will be a dermatologist.

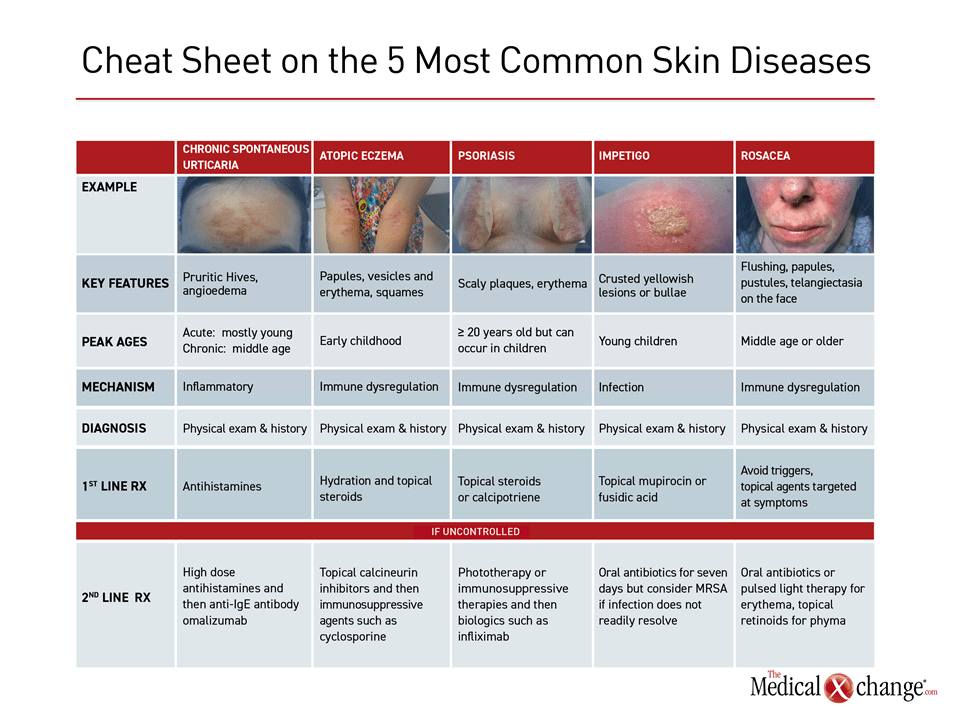

Additional Slide

(Fig. 3)References

1. Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:496-509.

2. Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:1029-72.

3. Sobolewski P, Walecka I, Dopytalska K. Nail involvement in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatologia 2017;55:131-5.

4. Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:278-85.

5. Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:512-6.

6. Boehncke WH, Schon MP. Psoriasis. Lancet 2015;386:983-94.

7. Lowes MA, Chamian F, Abello MV, et al. Increase in TNF-alpha and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressing dendritic cells in psoriasis and reduction with efalizumab (anti-CD11a). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:19057-62.

8. Bernhard JD. Clinical pearl: Auspitz sign in psoriasis scale. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:621.

9. Young M, Aldredge L, Parker P. Psoriasis for the primary care practitioner. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017;29:157-78.

10. Angelo JS, Kar BR, Thomas J. Comparison of clinical efficacy of topical tazarotene 0.1% cream with topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream in chronic plaque psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, right-left comparison study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:65.

Chapter 3: Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic disease characterized by well-demarcated scaly plaques driven by a hyperproliferative epidermis. Although it most commonly involves the scalp, elbows, and knees, it can develop on most skin surfaces, including the palms, soles, and genitalia. Nail involvement is observed in nearly 50% of patients. Total body involvement provides an objective measure of psoriasis severity, but it may not reflect the disease burden for patients self-conscious about lesions or who have persistent pruritus. Common phenotypes include guttate, pustular, annular, erythematous, and palmoplantar forms. The adverse impact of psoriasis on quality of life, including diminished self-esteem, is a well-documented feature.

In Canada, the estimated prevalence of psoriasis is 1.7%, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere. Psoriasis is considered an autoimmune inflammatory process. The most common age of onset is between the ages of 20 and 30 years, although psoriasis can develop in children. Up to 30% of patients also develop inflammation of the joints. Although many of the anti-inflammatory medications effective for psoriasis also reduce disease activity in the joints, psoriatic arthritis is typically managed separately. A variety of disease phenotypes classified by appearance or predominant site of involvement have been described, but psoriasis vulgaris is the most common form of the skin disease.

Show review