Expert Review

5 Most Common Skin Diseases in Primary Care

Chapter 5: Rosacea

Guest Editors

Jaggi Rao, MD, FRCPC

Kaushik Venkatesh, BS

Question & Answer from an Allergist’s Perspective

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

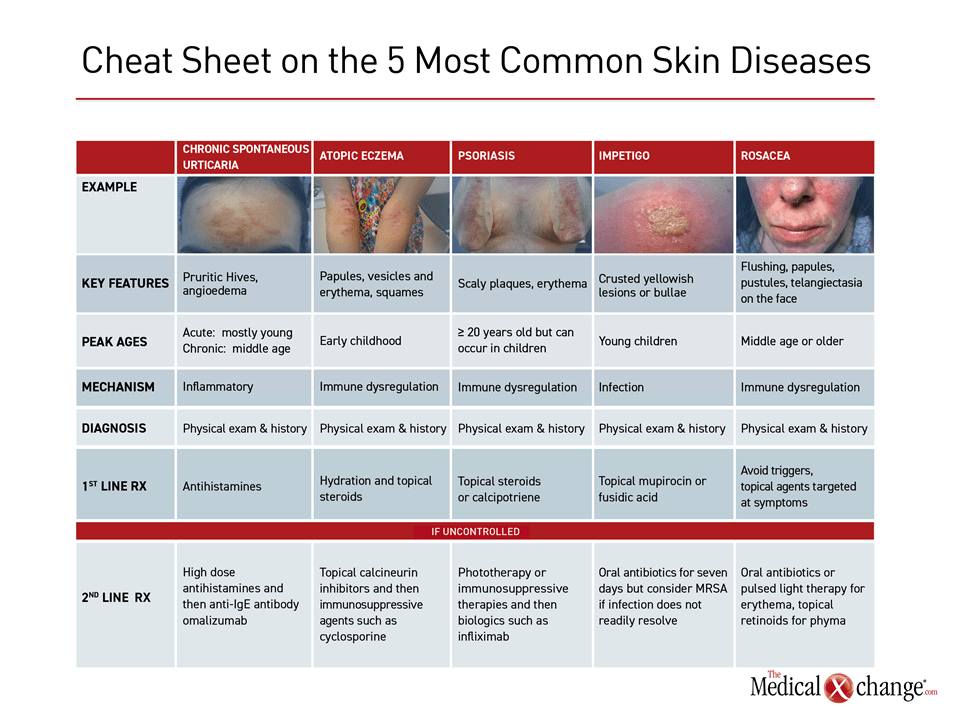

Rosacea is a chronic erythematous inflammatory condition with a relapsing-remitting course that primarily involves facial skin. Generalized flushing often accompanies the papules, pustules, telangiectasia, coarse skin, and hyperplasia that are characteristic of this condition. These episodes of pimply red rash may be transient, but chronic hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands, called phyma, can produce persistent sometimes irreversible skin changes, such as a bulbous nose in rhinophymatous rosacea. Burning, stinging, and facial edema often accompany active lesions. Vision impairment can occur in those with ocular involvement, but serious complications are uncommon. Rather, the disease burden derives largely from psychosocial consequences of facial lesions, which have been associated with negative effects on quality of life due to depression and anxiety.

The variable estimated prevalence of rosacea, which typically first develops in individuals between 30 and 50 years of age, ranges from 2% to 22% in predominantly fair-skinned populations. It is more common in women than in men. It has been estimated that more than three million Canadians have rosacea when extrapolated from an expected prevalence rate of 10%. The underlying causes of rosacea are unclear, but many patients associate the onset of flares with triggers such as stress, spicy food, hot beverages, ultraviolet light, and alcohol. Avoidance of triggers is a foundation of intervention. Although a long list of medications offer potential benefit based on empiric reports of efficacy, controlled trials with pharmacologic agents remain limited.

Pathophysiology

The U.S. National Rosacea Society has identified erythematotelangiectatic, papulo-pustular, phymatous, and ocular subtypes of rosacea.8 These may be useful for predicting course and guiding therapy, but it is unclear whether they differ by underlying mechanisms, and more than one type can occur in the same individual.2 The underlying inflammatory component of all forms of rosacea are most often attributed to alterations in innate immune function,9 but changes in adaptive immunity have also been reported.10 There is a variety of evidence supporting a genetic predisposition for rosacea.11 The importance of this predisposition relative to environmental factors remains incompletely defined. Overall, several factors may influence the development of rosacea, including facial vasculature traits, microbial organisms, exposure to chemical agents, dermal matrix degeneration, environmental trauma, physiology of nerve innervation, high density of facial sebaceous glands, reactive oxygen species, and under- or overexpression of certain signaling factors and proteins.12

Several comorbidities have been associated with risk of rosacea as well. Rosacea has been associated with other inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), suggesting a link to other types of immunologic dysfunction.12 It is also more common in patients with neurologic disorders, including migraine and complex regional pain syndrome.13 An upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which has been seen in both rosacea and neurologic disorders, is a potential link.14 Increased colonization of facial skin by Demodex folliculorum mites has been reported, which alone or association with genetic susceptibility might provoke an immune response leading to rosacea. Once the immune function is disturbed, triggers, such as heat or sun exposure, may drive disease through alterations in the skin’s microenvironment.15 Skin peeling and increased skin sensitivity may be due to water loss when scratching impairs the skin barrier function.16

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of rosacea is based on clinical features and history alone.7 Although a skin biopsy might be helpful to exclude differential diagnoses when clinical signs are ambiguous, the histopathology of rosacea is not unique and can be similar to that of other inflammatory skin diseases.1 When accompanied by transient flushing, a history of episodic rash in the central part of the face with papules, pustules, and/or telangiectasia supports a diagnosis of rosacea in the absence of another explanation for these symptoms (Fig. 1). Involvement can include the eyes and the neck in some individuals. Other features, such as burning or stinging and enlargement of the sebaceous glands are also consistent with the diagnosis.

The conditions most likely to be confused with rosacea include acne vulgaris, any of several forms of dermatitis affecting the face, such as contact dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis, and steroid-induced acneiform eruption.17 Potentially more serious but less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, drug reactions, and dermatomyositis. A family history of skin rash associated with the common triggers of rosacea, such as exposure to sunlight or alcohol, is common. The diagnosis may be easier to reach in those with long-standing symptoms because of the phymatous changes and more extensive erythema that develop when persistent rosacea is poorly controlled. Rosacea presents in a multitude of ways, and has been subclassified into four categories: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular.

Treatment

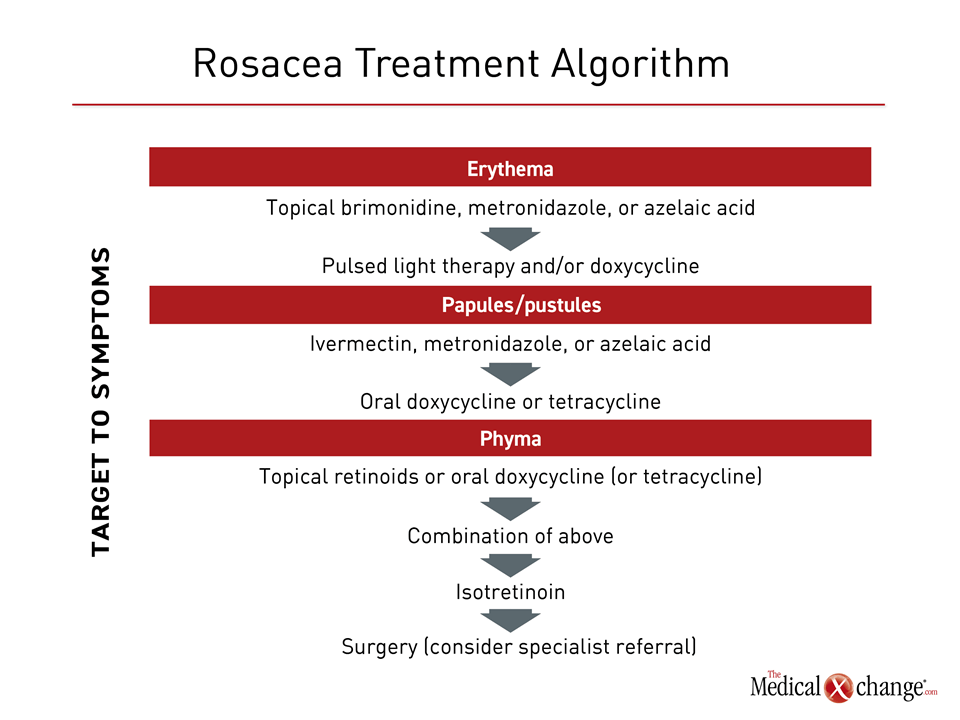

Avoidance of dietary, medicinal, and environmental triggers from is reasonably considered the first-line therapy for rosacea. Common triggering factors include extreme temperatures, spicy food, caffeine, physical exertion, emotions, and topical irritants, and medications that cause flushing.19 To identify triggers, patients are advised to journalize/document exposures, diet consumption, and activities leading up to flare-ups. According to guidelines issued by an expert panel of Canadian dermatologists, available pharmacologic therapies are best directed at individual symptoms. There is no pharmacologic therapy that addresses the underlying pathophysiology. For most symptoms, the Canadian guidelines make recommendations stratified by mild versus moderate-to-severe involvement. For example, the options for mild erythema are listed as topical brimonidine, metronidazole, and azelaic acid. Response should be evaluated after eight weeks. For severe erythema, intense pulsed light therapy or oral doxycycline can be added to the first-line agents, but specialist care might be appropriate. For papules and pustules, the options listed for mild involvement are topical ivermectin, metronidazole, or azelaic acid. Oral doxycycline or tetracycline can be added for moderate to severe disease if topical agents provide inadequate relief (Fig. 2).

For phyma, topical retinoids or an oral antibiotic (doxycycline or tetracycline) are recommended as a first step for mild involvement followed by the combination if adequate control is not achieved after at least eight weeks. Isotretinoin is an additional second-line option. For severe phyma, some form of surgery may be required. Ocular involvement, which typically requires some combination of lid care and artificial tears, should be referred to a specialist. In general, patients should also use daily broad-spectrum sunscreen to protect against UV-A and UV-B light, ideally with protective silicones and green-tinted for erythema.

Due to the chronicity of rosacea, patients should be considered for maintenance therapy and re-evaluated regularly in order to adjust treatment. When used for maintenance, several of the topical agents recommended for acute control, including metronidazole,18 ivermectin,19 and brimonidine,20 have been associated with a reduced risk of relapse.

Summary

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease most often involving the cheeks, nose, chin, and forehead. The relapsing-remitting features, which include erythema, papules, pustules, and telangiectasia, are often associated with triggers, such as exposure to UV light, spicy foods, psychological stress, and alcohol consumption. Avoidance of triggers is the first step to reduce risk and severity of flares. The same topical therapies used to control acute symptoms can be considered in maintenance regimens to reduce risk of relapses. For severe or ocular involvement, specialist care is appropriate. Due to the risk of irreversible skin changes from persistent erythema and phyma, early diagnosis and aggressive symptom control is appropriate. Although serious complications are uncommon, the facial involvement that is typical of rosacea imposes psychological distress and reduces quality of life for many affected individuals.

Rosacea: The Allergist’s Perspective:

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Internal Medicine

Toronto Allergy and Asthma Clinic

Toronto, Ontario

1. Should rosacea be considered an allergic or dermatologic disease?

Rosacea is an inflammatory condition, but its relationship to hypersensitivity is uncertain. Although skin mite colonization is considered a potential etiologic factor, the inflammatory pathways typically upregulated in an atopic response are not closely associated with rosacea. It is therefore largely regarded as a dermatologic condition. There is some connection to immune dysregulation and a microbiome imbalance that causes an aberrant immune shift to commensal organisms such as Malassezia furfur but these are typically not type II inflammatory issues.

2. When is it appropriate to refer a patient with rosacea to a specialist?

As the underlying pathophysiology of rosacea remains incompletely understood, current treatments focus on avoiding known triggers and topical therapies that ameliorate the skin manifestations. Patients with significant and persistent phyma are at risk of permanent skin changes. Such patients and those with ocular involvement are candidates for specialist care. Although some foods such as chocolate and alcohol are known to flare up rosacea, these are not mediated through an IgE reaction and as such as not allergies. Patients with rosacea can get flares of contact dermatitis like anyone else which sometimes causes diagnostic confusion.

3. If patients do not respond to first- or second-line treatment for rosacea, what is the most appropriate specialist referral, a dermatologist or an allergist?

In cases of rosacea refractory to first-line therapies, particularly in cases of progressive phyma, dermatologists typically have more experience with third-line interventions, such as retinoids or phototherapy, than other specialists. Although demodex mites are among suspected triggers, in suggesting an inflammatory, allergic-like underlying pathophysiology, dermatologists are generally consulted before allergists for difficult cases.

Additional Slide

(Fig. 3)References

1. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:749-58; quiz 59-60.

2. van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1754-64.

3. Egeberg A, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, Thyssen JP. Patients with Rosacea Have Increased Risk of Depression and Anxiety Disorders: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Dermatology 2016;232:208-13.

4. Halioua B, Cribier B, Frey M, Tan J. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:163-8.

5. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, Jansen T, Layton A, Picardo M. Rosacea – global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:188-200.

6. Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:S27-35.

7. Asai Y, Tan J, Baibergenova A, et al. Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rosacea. J Cutan Med Surg 2016;20:432-45.

8. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:584-7.

9. Bevins CL, Liu FT. Rosacea: skin innate immunity gone awry? Nat Med 2007;13:904-6.

10. Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and Morphological Characterization of Inflammatory Infiltrate in Rosacea Reveals Activation of Th1/Th17 Pathways. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:2198-208.

11. Awosika O, Oussedik E. Genetic Predisposition to Rosacea. Dermatol Clin 2018;36:87-92.

12. Laquer V, Hoang V, Nguyen A, Kelly KM. Angiogenesis in cutaneous disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:945-58; quiz 59-60.

13. Spoendlin J, Karatas G, Furlano RI, Jick SS, Meier CR. Rosacea in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: A Population-based Case-control Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:680-7.

14. Spoendlin J, Voegel JJ, Jick SS, Meier CR. Migraine, triptans, and the risk of developing rosacea: a population-based study within the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:399-406.

15. Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases and their multiple roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:205-16.

16. Woo YR, Lim JH, Cho DH, Park HJ. Rosacea: Molecular Mechanisms and Management of a Chronic Cutaneous Inflammatory Condition. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17.

17. Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis 2013;92:234-40.

18. Oge LK, Muncie HL, Phillips-Savoy AR. Rosacea: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2015;92:187-96.

19. M.W. G, Burova EP. Flushing: causes, investigation, and clinical consequences. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 1997;8:91-100.

20. Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:679-83.

21. Stein Gold L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Long-term safety of ivermectin 1% cream vs azelaic acid 15% gel in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: results of two 40-week controlled, investigator-blinded trials. J Drugs Dermatol 2014;13:1380-6.

22. Moore A, Kempers S, Murakawa G, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of a 1-year open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol 2014;13:56-61.

Chapter 5: Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic erythematous inflammatory condition with a relapsing-remitting course that primarily involves facial skin. Generalized flushing often accompanies the papules, pustules, telangiectasia, coarse skin, and hyperplasia that are characteristic of this condition. These episodes of pimply red rash may be transient, but chronic hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands, called phyma, can produce persistent sometimes irreversible skin changes, such as a bulbous nose in rhinophymatous rosacea. Burning, stinging, and facial edema often accompany active lesions. Vision impairment can occur in those with ocular involvement, but serious complications are uncommon. Rather, the disease burden derives largely from psychosocial consequences of facial lesions, which have been associated with negative effects on quality of life due to depression and anxiety.

The variable estimated prevalence of rosacea, which typically first develops in individuals between 30 and 50 years of age, ranges from 2% to 22% in predominantly fair-skinned populations. It is more common in women than in men. It has been estimated that more than three million Canadians have rosacea when extrapolated from an expected prevalence rate of 10%. The underlying causes of rosacea are unclear, but many patients associate the onset of flares with triggers such as stress, spicy food, hot beverages, ultraviolet light, and alcohol. Avoidance of triggers is a foundation of intervention. Although a long list of medications offer potential benefit based on empiric reports of efficacy, controlled trials with pharmacologic agents remain limited.

Show review