Expert Review

Proper Use of Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation

Chapter 2: Strokes in an Era of Effective Prevention

Theodore Wein, MD

Assistant Professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery

McGill University

Montreal, Quebec

In Canada, about one fifth of ischemic strokes are attributed to atrial fibrillation (AF). Of stroke causes, AF-associated stroke is considered one of the most preventable. The benefit of the vitamin K antagonist warfarin has been clearly established in multiple large clinical trials and subsequent trials with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have shown a similar benefit associated with a lower risk of bleeding. The problem is that these drugs are underutilized at least in part due to fear of inducing bleeding. The guidelines for use of oral anticoagulants are relatively simple and evidence-based, but studies show that these agents are frequently withheld or NOACs are used in reduced dosages to avoid risk of bleeding. Modified dosing is appropriate in a few well-defined subgroups, but due to the devastating consequences of major strokes, the benefit-to-risk ratio favors full doses of NOACs in the majority of AF patients who are candidates for stroke prevention.

The Persistent Problem of No or Inadequate Anticoagulation

In randomized trials, oral anticoagulation in patients with AF reduces the risk of stroke by up to 85% relative to no treatment and by 50% relative to aspirin alone.1-3 The benefit-to-risk ratio of stroke prevention favors oral anticoagulation in almost all patients because the risk of serious debilitating and life-threatening strokes is high, typically overwhelming the relatively modest risk of clinically significant bleeding, according to the evidence-based guidelines.4-6 In a population-based net-benefit calculation of 182,678 subjects in Sweden, it was estimated that only 3.9% of AF patients would not benefit.7 These were AF patients at lowest risk, defined as a score of 0 on the CHA2DS2-VASc calculator. Such patients are already excluded from oral anticoagulation in current guidelines.

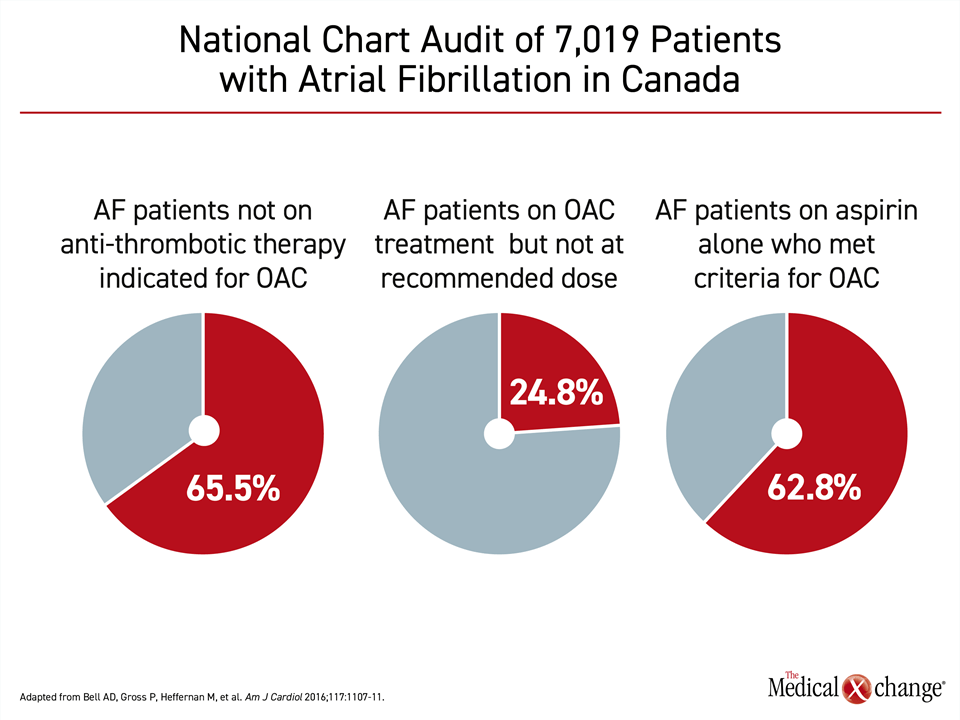

In recommending routine stroke prevention with oral anticoagulation in all AF patients, except those younger than 65 years of age with no vascular risk factors, such as hypertension or diabetes, the major guidelines are consistent.5,6,8 Yet, there are numerous sets of data suggesting that a substantial proportion of AF candidates for oral anticoagulation are being undertreated. In a national chart review of more than 7000 patients with nonvalvular AF undertaken in Canada, 65.5% of those not taking any oral anticoagulant were candidates by guideline criteria, while 24.8% of those receiving oral anticoagulation were not on the recommended dose9 (Fig. 1).

In AF patients on oral anticoagulation who have a stroke, inadequate dosing has been documented repeatedly. In one study of 60 patients on a NOAC, more than one third (34.1%) were prescribed a subtherapeutic dose and 25% were not adherent to their treatment.10 In a study undertaken in Canada, an analysis of 24 patients who had an ischemic stroke while on a NOAC found that only 10 (42%) were taking an appropriate dose.11 Of the remaining, seven were on long-term therapy with a lower-than-recommended dose and six did not receive recommended NOAC treatment when undergoing surgery.

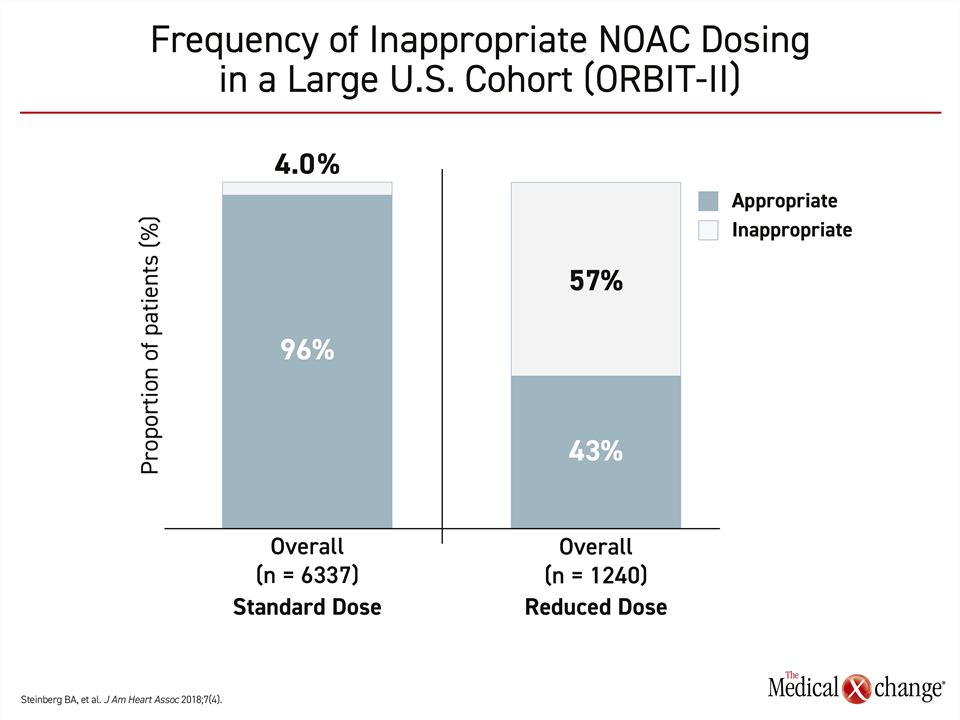

When inappropriate doses of oral anticoagulation are prescribed, the problem by far is too little therapy rather than too much. In the ORBIT-II trial, which evaluated NOAC use in nearly 8000 patients, 57% of those taking a reduced dose were undertreated by guideline criteria.12 Of those on standard doses, just 4% were overdosed (Fig. 2)). When compared, those on a reduced dose had a 50% increased likelihood of a thromboembolic event (HR 1.56) and a more than two-fold increased likelihood of death (HR 2.61) relative to those on a standard dose. After risk adjustment, these risks were no longer significant, but the authors maintained that this does not negate the finding that most patients on reduced doses of NOACs are not being treated according to product monograph recommendations.

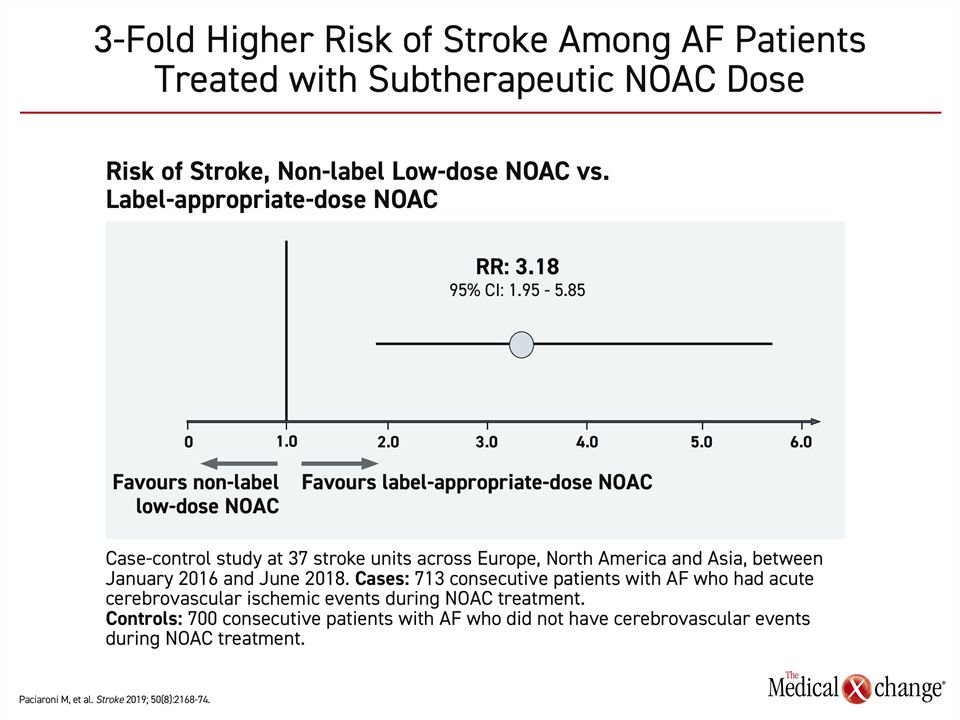

In a multinational case-control study that compared 713 consecutive AF patients with an ischemic stroke to 700 consecutive AF patients without a cerebrovascular event, low doses of NOACs were associated with a more than three-fold increased odds ratio (OR 3.18; 95% CI, 1.95 – 5.85) of ischemic events on a multivariate analysis.13 This increase was statistically significant (Fig. 3). Many patients on low doses of NOACs had a history of bleeding or were on concomitant antiplatelet therapy, which were cited as reasons for a fear of bleeding and the justification for a low-dose regimen.

Presumably, many patients are prescribed reduced doses of NOACs in an effort to lower bleeding risk, but this practice is not consistent with guideline recommendations. In a study of 14,865 AF patients, 1,473 (9.9%) were on a reduced NOAC dose due to renal dysfunction. However, 13.3% of the remaining 13,392 were also on a lower dose with no clear indication although advanced age was associated with underdosing.14 In these patients, the risk of stroke was increased almost five-fold (HR 4.87; 95% CI, 1.30 – 18.26). Yet, the lower dose was not associated with significant protection from major bleeding. In a trial that showed significantly greater adherence to once-daily NOAC than twice-daily NOAC therapy, there was no significant increase in minor or major bleeding in the group on once-daily therapy.15

Many of the risk factors for AF and stroke associated with AF, such as advancing age, are also risk factors for bleeding. The guidelines recommend full doses of oral anticoagulation even in patients with risk factors for bleeding on the basis of benefit-to-risk calculations that favor stroke prophylaxis when these competing risks are calculated together. Although many guidelines recommend bleeding risk assessment with the goal of correcting those that are modifiable, low risk of stroke rather than high risk of bleeding is the major reason for exempting patients from long-term oral anticoagulation.

The Health and Financial Cost of Non-Adherence

When compared to vitamin K antagonists, NOACs have several advantages that have led them to be granted preferred status in major guidelines. In one large analysis of randomized trials, NOACs were at least as effective as warfarin for prevention of stroke but were associated with a significantly lower risk of hemorrhagic strokes and other major bleeding events.16 In addition, NOACs provide an antithrombotic effect on the first day, accelerating the time to protection when compared to the two to four days typically required after initiation of warfarin to reach therapeutic levels. NOACs, by circumventing the need for therapeutic monitoring, are also easier to administer. In one study of AF patients admitted for ischemic stroke while taking an oral anticoagulant, the dose at admission was subtherapeutic in 91.7% of those on a vitamin K antagonist (international normalized ratio [INR] <2.0) versus 43% of those on a NOAC.10

Of the obstacles to stroke prevention with oral anticoagulation in patients with AF, none are likely to be more important than adherence. In a recent population-based cohort study, more than 40% of AF patients initiating oral anticoagulation were not fully adherent whether receiving warfarin or a NOAC 12 months after initiating therapy.17 For a group of therapies with a low risk of side effects, intolerance is an unlikely explanation for diminishing adherence over time. Rather, simple regimens that are easy to remember and to take appear to improve adherence to oral anticoagulants as they have for other conditions requiring chronic therapy, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or hypertension.18,19

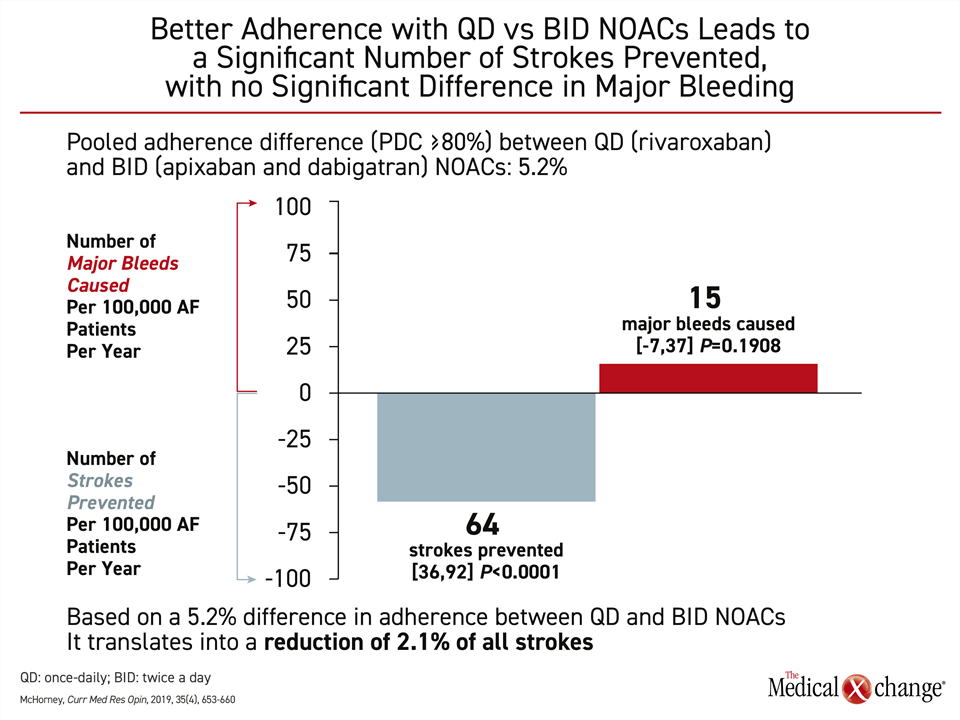

In one multicenter cross-sectional study of 2214 AF patients taking NOACs for at least three months, a once-daily NOAC increased the likelihood of adherence by more than 10% (P=0.001).15 Speculation that twice daily dosing might better compensate for missed doses is not supported by a study that addressed this question. When AF patients with suboptimal adherence to once- versus twice-daily oral anticoagulation were compared, stroke rates were nearly identical.20 In another study assessing once-versus twice-daily dosing, a substantially improved benefit-to-risk ratio was identified in real-world data. In a claims database of more than 50,000 patients, a non-significant increase of 15 major bleeds (P<0.191) among those taking once- versus twice-daily NOAC was counterbalanced by 64 fewer strokes (P<0.001)21 (Fig. 4). The reduction in strokes was associated with a large cost saving.

Sustaining Benefits of Anticoagulation

Due to the important protection afforded by oral anticoagulation against stroke in patients with AF, strategies to sustain optimal protection have been developed for specific situations in which the benefit-to-risk of this therapy might be altered. This includes those undergoing a surgical procedure, those who have a first ischemic stroke, and those who have had a hemorrhagic stroke. In a retrospective study conducted at McGill, six of 14 strokes in AF patients attributed to inappropriate NOAC use involved inappropriate discontinuation or an unnecessarily prolonged discontinuation of the anticoagulant for a surgical procedure.11

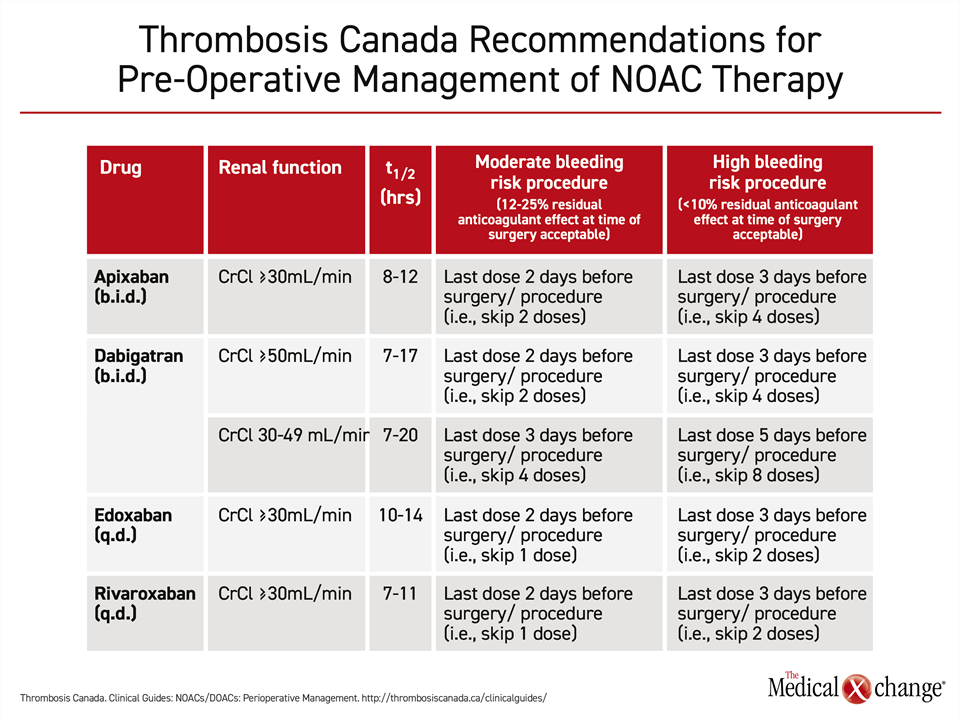

For perioperative risk management, Thrombosis Canada offers specific although similar recommendations for each of the available NOACs: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.22 In all cases, discontinuation of oral anticoagulants, whether NOACs or warfarin, is not recommended for minor surgery, such as root canals, cataract procedures, coronary angiography, or pacemaker insertion. For surgery associated with moderate risk of bleeding, such as orthopedic, vascular, or laparoscopic surgery, discontinuation of the NOAC two days before the surgery is recommended for those with normal renal function but three days prior in those with impaired renal function taking dabigatran. Withholding NOACs three days prior to surgery is also recommended for high-risk procedures, such as neurosurgery, major cardiac surgery, or extensive cancer resections. The exception is for those on dabigatran with renal impairment in which drug discontinuation is recommended five days in advance (Table 1).

Following surgery with moderate bleeding risk, all of the oral anticoagulants should be resumed the day after the procedure. Following surgery with a high bleeding risk, resumption should take place 48 to 72 hours after surgery, although an earlier prophylactic dose can be considered.

For episodes of bleeding unrelated to surgery, oral anticoagulants should be continued if bleeding is expected to be self-limited, such as bruising, according to Thrombosis Canada.23 For major bleeding requiring medical attention, it is reasonable to consider withholding oral anticoagulation until the bleeding has stopped. This decision should be made within the context of bleeding severity and the expected duration of anticoagulant effect, which relates to such factors as timing of the last dose and drug half-life. If the risk posed by uncontrolled bleeding is considered to exceed the risk of a thromboembolism, additional steps, such as the introduction of an anticoagulation drug reversal agent, if available, might be appropriate. Oral anticoagulation should be resumed as quickly as possible after bleeding has been controlled and the risk of rebleeding is low.

In AF patients who have had a stroke, oral anticoagulation should be started or resumed as quickly as possible for secondary prevention. In this case, as in primary prevention, NOACs are preferred.24 The exceptions are those who have a mechanical heart valve, for whom warfarin with tight INR monitoring is preferred. All patients with a stroke should be screened for the presence of AF and placed on oral anticoagulation for secondary prevention if this arrhythmia is found.

In AF patients who have had a cerebrovascular event, the optimal timing for resuming oral anticoagulation is not evidence-based. According to one expert consensus, starting or resuming treatment on the same day or within one day of a TIA, three days of a mild stroke, six days of a moderate stroke, and 12 days of a severe stroke is reasonable.24 Several large randomized trials evaluating early and late start of NOACs to prevent recurrent stroke are in progress, three of which will yield data before the end of 2021.

Similarly, the optimal time to resume oral anticoagulation in AF patients following an intracranial hemorrhage is unknown.25 In a review, modifiable risks were identified for stroke and recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage. The authors counseled individualizing the decision to resume anticoagulation based on both. More guidance is expected from the ongoing trial that will randomize patients at different time intervals following intracranial hemorrhage to a low- or high-dose NOAC regimen.26 Outcomes will be compared at 24 months.

Summary

Appropriate use of oral anticoagulation presents a major opportunity to reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity associated with stroke. Approximately one in five strokes are associated with AF, patients with AF are five times more likely to have a stroke than matched patients without AF, and AF-associated strokes are more likely to lead to disability than strokes of other types.27 Based on data that support the premise that most strokes related to AF can be prevented with oral anticoagulation, it is essential for clinicians to screen aging patients for AF and to initiate oral anticoagulation in all but those under the age of 65 without other stroke risk factors, such as vascular disease or congestive heart failure.

The frequency with which patients with known AF are not receiving oral anticoagulation or are receiving subtherapeutic doses emphasizes a need to reevaluate obstacles. For providers, concern about bleeding in patients who are elderly, have a history of bleeding, or are considered to be at high risk of bleeding has been identified as a source of hesitation or uncertainty regarding full-dose therapy. Similarly, failure to resume anticoagulation after surgery, after a significant bleeding event, or after a first stroke, might represent missed opportunities for stroke prevention. Guidelines outline evidence-based strategies for most of these scenarios. All of the obstacles to stroke prevention in AF patients, including inadequate adherence, are readily addressed by a more rigorous and systematic approach.

References

- Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation I, Singer DE, Hughes RA, et al. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1505-11.

- Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, James KE, et al. Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Veterans Affairs Stroke Prevention in Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1406-12.

- Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. Final results. Circulation 1991;84:527-39.

- Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res 2014;114:1453-68.

- Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893-962.

- January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2019;140:e125-e51.

- Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation 2012;125:2298-307.

- Andrade JG, Verma A, Mitchell LB, et al. 2018 Focused Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:1371-92.

- Bell AD, Gross P, Heffernan M, et al. Appropriate Use of Antithrombotic Medication in Canadian Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1107-11.

- Fernandes L, Sargento-Freitas J, Milner J, et al. Ischemic stroke in patients previously anticoagulated for non-valvular atrial fibrillation: Why does it happen? Rev Port Cardiol 2019;38:117-24.

- Wein T. Strokes in atrial fibrillation patients already on oral anticoagulation. Int J Stroke 2017;12(4_suppl):Abstract.

- Steinberg BA, Shrader P, Pieper K, et al. Frequency and Outcomes of Reduced Dose Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Anticoagulants: Results From ORBIT-AF II (The Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation II). J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7.

- Paciaroni M, Agnelli G, Caso V, et al. Causes and Risk Factors of Cerebral Ischemic Events in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Treated With Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention. Stroke 2019;50:2168-74.

- Yao X, Shah ND, Sangaralingham LR, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant Dosing in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Renal Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:2779-90.

- Emren SV, Zoghi M, Berilgen R, et al. Safety of once- or twice-daily dosing of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A NOAC-TR study. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2018;18:185-90.

- Salazar CA, del Aguila D, Cordova EG. Direct thrombin inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD009893.

- Chen N, Brooks MM, Hernandez I. Latent Classes of Adherence to Oral Anticoagulation Therapy Among Patients With a New Diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1921357.

- Toy EL, Beaulieu NU, McHale JM, et al. Treatment of COPD: relationships between daily dosing frequency, adherence, resource use, and costs. Respir Med 2011;105:435-41.

- Flack JM, Nasser SA. Benefits of once-daily therapies in the treatment of hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2011;7:777-87.

- Alberts MJ, Peacock WF, Fields LE, et al. Association between once- and twice-daily direct oral anticoagulant adherence in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients and rates of ischemic stroke. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:11-3.

- McHorney CA, Peterson ED, Ashton V, et al. Modeling the impact of real-world adherence to once-daily (QD) versus twice-daily (BID) non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants on stroke and major bleeding events among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2019;35:653-60.

- ThrombosisCanada. NOACs/DOACs: Perioperative Management. Thrombosis Canada 2018.

- ThrombosisCanada. NOACs/DOACs: Management of Bleeding. Thrombosis Canada 2019.

- Wein T, Lindsay MP, Cote R, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: Secondary prevention of stroke, sixth edition practice guidelines, update 2017. Int J Stroke 2018;13:420-43.

- Li YG, Lip GYH. Anticoagulation Resumption After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2018;20:32.

- clinicaltrials.gov. Edoxaban for intracranial hemorrhage survivors with atrial fibrillation (ENRICH-AF). Clinical Trials, US National Library of Medicine 2020:Access June 12, 2020.

- European Heart Rhythm A, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Camm AJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-429.

Chapter 2: Strokes in an Era of Effective Prevention

In Canada, about one fifth of ischemic strokes are attributed to atrial fibrillation (AF). Of stroke causes, AF-associated stroke is considered one of the most preventable. The benefit of the vitamin K antagonist warfarin has been clearly established in multiple large clinical trials and subsequent trials with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have shown a similar benefit associated with a lower risk of bleeding. The problem is that these drugs are underutilized at least in part due to fear of inducing bleeding. The guidelines for use of oral anticoagulants are relatively simple and evidence-based, but studies show that these agents are frequently withheld or NOACs are used in reduced dosages to avoid risk of bleeding. Modified dosing is appropriate in a few well-defined subgroups, but due to the devastating consequences of major strokes, the benefit-to-risk ratio favors full doses of NOACs in the majority of AF patients who are candidates for stroke prevention.

Show review