Expert Review

Management of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Women: Awareness & Treatments

Chapter 2: Treatments – Psychology

Lori A. Brotto PhD, R Psych

Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, The University of British Columbia,

Executive Director, Women's Health Research Institute

Canada Research Chair in Women's Sexual Health

Vancouver, BC

Atlanta – Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder is a condition that is estimated to affect 10% of adult women.1 Psychological treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness can be employed to treat these women. Clinicians need to recognize cultural or religious factors that influence the patient, as well as mental health conditions that may need to be addressed in women who present with reduced sexual desire.

Introduction

As mentioned in Chapter 1, a complex interplay of biopsychosocial and cultural factors influence sexual desire.2 Although the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) replaced hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) with sexual interest/arousal disorder (SIAD) in 2013,3 there are no validated instruments available to make a diagnosis of SIAD at the present time. A diagnosis of HSDD can be made using a variety of instruments. The Decreased Sexual Desire Screener,4 which can identify generalized and acquired HSDD in women, is a validated tool to detect persistent loss of sexual desire marked by personal distress (Fig. 1). Some of the challenges that clinicians face when making a diagnosis of HSDD or SIAD can include separating other commonly co-occurring conditions (such as stress, anxiety, or depression from reduced desire5) or identifying life experiences (such as past sexual trauma, or pinpointing cultural beliefs) that can affect sexual desire.5 It may be necessary to treat co-occurring conditions to effectively improve women’s low or absent sexual desire. Often, psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or mindfulness-based therapy can be implemented to address both long-standing reduced sexual desire that causes personal distress or a fairly new phenomenon of decreased sexual desire that causes personal distress, as well as these psychological comorbidities.

The Impact of Low Desire

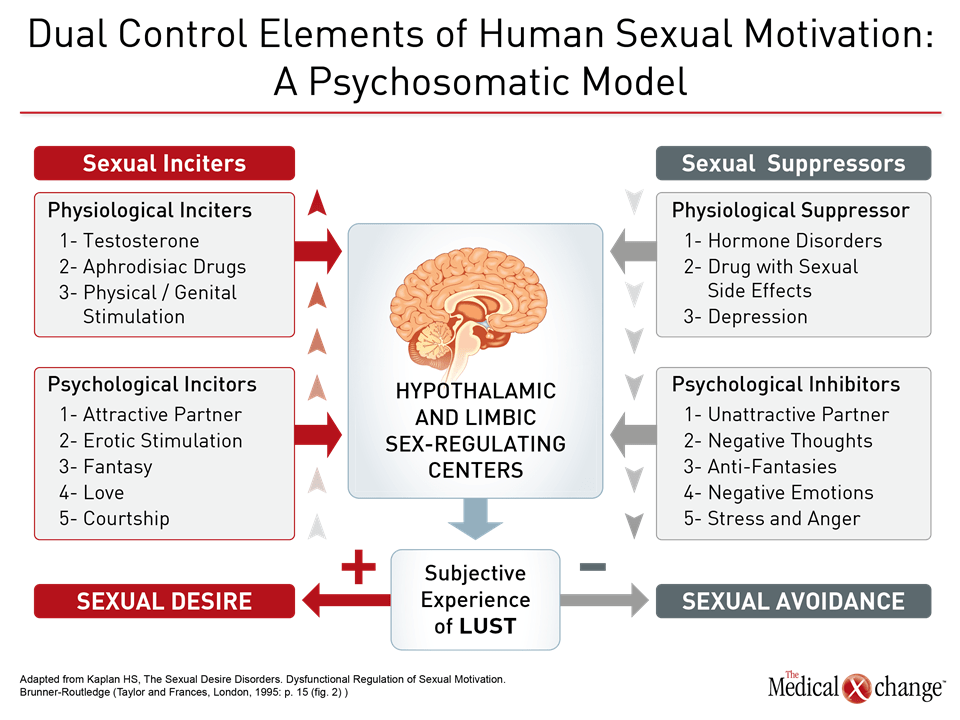

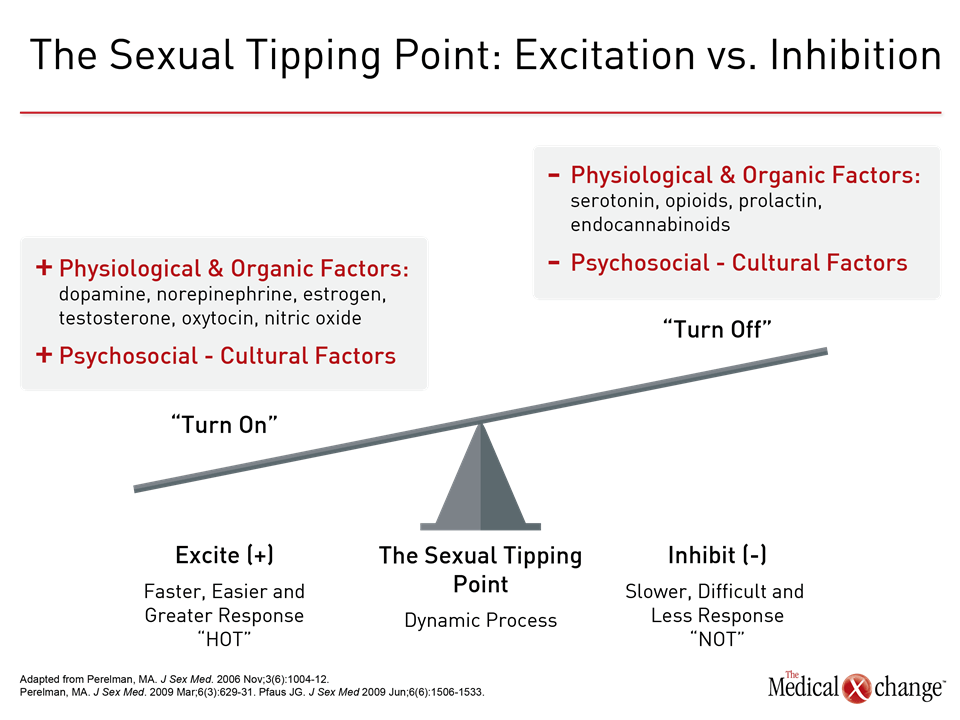

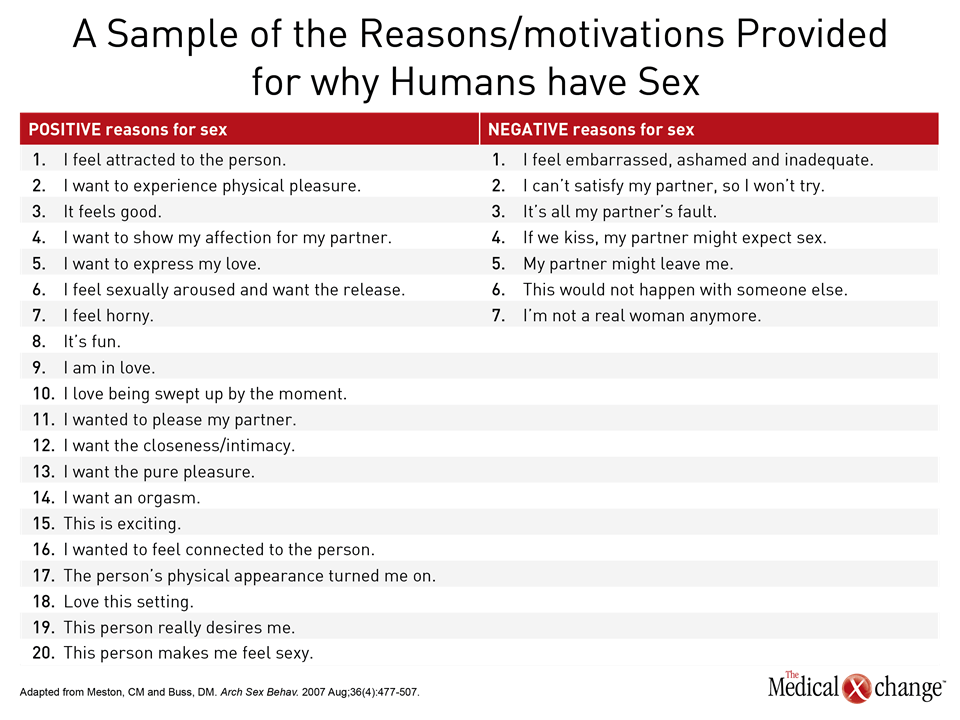

Diminished sexual desire is the most frequent sexual complaint that women have.6,1 There is no one cause for reduced sexual desire. Research suggests that sexual response, and by extension sexual problems, can arise from an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory neurobiological pathways regulating the sexual response in mammals, known as the Dual Control Model.7 Helen Singer Kaplan, a pioneer in the field of sex therapy, depicted this as sexual inciters and sexual suppressors (Fig. 2). Dr. Michael Perelman, Co-director, Human Sexuality Program, Clinical Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, Reproductive Medicine and Urology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, has depicted this imbalance in the Sexual Tipping Point® model,8 which puts forth that positive physical and mental factors increase sexual response while negative physical and mental factors inhibit sexual response. Speaking at an instructional course on psychological approaches to female sexual dysfunction at this year’s ISSWSH, Dr. Perelman has suggested that an integrated method can address the etiology and management of female sexual dysfunction (Fig. 3).8 Diminished desire can affect a woman’s sense of self, according to Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg, Chief, Division of Behavioral Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Ohio. “Women who have a loss of desire are much more negative in many aspects of their lives,” explained Dr. Kingsberg. “HSDD has a downstream effect on how women see themselves.”

“HSDD has a downstream effect on how women see themselves.”

Indeed, findings from a survey that Dr. Kingsberg conducted support the contention that HSDD has “a reach far outside the bedroom”. The survey, based on 450 women aged 20 to 60, found more than 70% of women attributed negative impacts on body image and self-confidence.9 Interestingly, respondents to the survey did not view distressing reduced sexual desire as a medical condition that could be treated and did not report their reduced sexual desire to their healthcare providers.9 The findings from the survey also suggest that healthcare providers may need to introduce the topic of sexual functioning and sexual desire in their interaction with their patients, since patients may not raise the topic of their decreased desire without being prompted to do so. The PLISSIT model outlines possible ideas for office-based counseling and education, and suggests that primary care physicians with even limited training in sexual health should, at a minimum, give their patients permission to discuss sexual concerns, and provide limited information such as accurate information about the nature of sexual response and common predictors of sexual problems.10 Of note, there is scant literature examining the frequency of HSDD in women in same-sex relationships or women seeking same-sex intimate interactions. There is also the possibility that with psychotherapy, a woman may come to realize that she is no longer attracted to men and that she has sexual desire and attraction for other women, noted Dr. Althof. There remains a need for exploration of psychological treatments within the framework of clinical studies to provide robust data on the efficacy of psychological interventions and to identify predictors of success that will permit clinicians to better match specific psychological therapies to the needs of women seeking treatment for low or absent sexual desire.

The Patient Interview

It is paramount that clinicians conduct a thorough patient interview to try and identify all the possible factors that may be contributing to decreased desire or to evaluate whether diminished desire has given rise to other conditions, including poor body image and decreased self-confidence. By asking a series of focused questions and taking a quick sex status,11 a healthcare provider can determine what factors are affecting sexual desire, according to Dr. Perelman. He spoke recently at ISSWSH about the value of taking a sex status, noting one of the key components of taking a sex status is asking about a patient’s last sexual experience and aspects of that experience. At this year’s ISSWSH, Dr. Perelman gave an example of an interaction with a patient in which deep-seated cultural beliefs can affect a woman’s sexual desire. If a woman is ultra-Orthodox Jewish, for instance, a psychotherapist may have to reach out to a religious authority, such as a rabbi, who would grant permission for a couple to be exposed to sources of eroticism in an effort to stimulate desire and have the couple enjoy a mutually-satisfying sexual experience. Among the many different physical contributors to low sexual desire is pelvic floor dysfunction. For example, a woman’s pelvic floor tightness associated with a fear of penetration may lead her to eventually lose desire for sex12 and, in such cases, pelvic floor physiotherapy to address the pelvic floor tone, combined with psychosocial approaches to address the anxiety, may be necessary in order to improve the woman’s sexual desire. Depression is a very common condition, and research has found considerable comorbidity between reduced desire and major depressive disorder.13 Each condition can ultimately worsen the other. Furthermore, there may be a negative impact of anti-depressant medication on sexual response.13 It is vital that clinicians keep the relationship between depression and sexual function top of mind when assessing a woman presenting with low or absent sexual desire. Mindfulness has been an approach that has demonstrated success in treating depressed mood in women with low sexual interest.14 The patient interview may serve as an opportunity to investigate relationship dynamics and how they are affecting sexual desire and sexual functioning in a way that brief screeners cannot. Reduced sexual desire can be the result of an unsatisfying relationship or decreased sexual desire can result in partner avoidance in addition to hostility and antagonism in a relationship. Communication skills training may be a helpful strategy to improve intimacy and may prove to have a positive impact on sexual desire.

Sex Therapy

Several types of psychological interventions can be initiated to address low or absent sexual desire, noted Dr. Stanley Althof, Professor Emeritus of Psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, and Executive Director of the Center for Marital and Sexual Health of South Florida in West Palm Beach, Florida, addressing attendees at an instructional course on psychological approaches to female sexual dysfunction at this year’s ISSWSH. One of the most long-standing psychological approaches is sex therapy, which targets issues such as sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain. It can be conducted on an individual basis, between a couple, or in a group setting, and typically lasts for a finite amount of time (e.g., three months with weekly sessions). Sex therapy can consist of exercises such as sensate focus, which includes non-demand sensual touching designed to enhance sexual desire in a gradual manner and decrease the avoidance of sexual activity.15 “Sensate focus is a way of having couples touch each other and give each other feedback about what is pleasurable and what is not,” explained Dr. Althof, in an interview following the instructional course. “They can engage in this practice at home. The idea is to not focus on intercourse but to have a woman not feel anxiety about sex.”

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

One of the objectives of CBT is to pinpoint behavior and thoughts (cognitions) that are contributing to decreased sexual desire, and eliciting negative emotions which further drive the unhelpful behaviors and maladaptive thoughts (Fig. 4). A core aspect of CBT involves using a journal or diary to track negative sex-related encounters, and identify the specific thoughts the woman experienced in that situation. Then, using a technique called cognitive restructuring, she is invited to evaluate the evidence for and against that thought, and to consider revising it to a more accurate and adaptive thought. As a result of adjusting maladaptive thoughts, CBT predicts that behavior and emotions improve as a result. CBT can also include an educational component, and involves informing a woman, or both a woman and her sexual partner, about using adequate erotic and physical stimulation to heighten sexual desire and arousal. From a CBT perspective, when the feelings of sexual arousal improve, then associated thoughts and behaviors are also affected.

Mindfulness

Because of the widespread prevalence of cognitive distraction during sexual activity, as well as the vast number of negative and judgmental thoughts that women have about themselves and about sex, mindfulness has arisen as a possible strategy to improve sexual desire. Mindfulness is defined as present moment, non-judgmental, awareness.16 Mindfulness aims to teach the woman skills in remaining focused on a particular target, such as bodily sensations, the breath, and sounds, and to notice but not get caught up in the contents of negative thoughts. There is evidence that mindfulness can strengthen the connection between genital and subjective arousal and therefore improve sexual arousal concordance.17 A number of studies found four sessions of group mindfulness-based therapy to improve sexual desire.18 More recently, however, experts have turned exclusively to 8-session group mindfulness programs, as they simulate the standardized protocols used for individuals with chronic pain, anxiety, and depression. One study found this 8-session group mindfulness-based program, which included mindfulness exercises conducted at home, produced improvements in sexual desire, overall sexual function, and sex-related distress, regardless of the duration of decreased desire.14 One of the benefits that has been observed through using mindfulness is potential improvements in the regulation of attention, emotion, and self-awareness. Indeed, there is evidence suggesting that the practice of mindfulness can lead to neuroplastic alterations in the structure and function of the brain areas that are linked to the regulation of attention, emotion, and self-awareness.18 “There can be a high level of distractibility,” explained Dr. Althof, speaking in an interview at this year’s ISSWSH. “A woman may be pre-occupied with her work, may be thinking about taking care of her kids or a sick parent, and may be thinking about all the things she has scheduled in her life.” Dr. Kingsberg said many women with HSDD are aware that sexual activity can offer pleasure but no longer have a motivation to seek out this pleasure on an ongoing basis. “There is a lack of wanting,” she said, agreeing with Dr. Althof that CBT and/or mindfulness can assist women to focus on what is relevant to a sexual encounter and ignore elements that distract from sexual interaction. Part of a therapeutic recommendation may include requesting that a partner avoid making any demands for sexual intercourse, so that a woman does not feel ongoing pressure to have regular intercourse in daily life, explained Dr. Althof.

The Widespread Application of CBT and Mindfulness

Psychological treatments such as CBT and mindfulness are appropriate for women who have decreased desire that is causing them distress after specific medical therapy.2 The feasibility of mindfulness-based programs to improve sexual desire and decrease sexual-related distress, amongst other outcomes, in women with cervical and endometrial cancer has been studied. Brief sessions involving a combination of education, CBT, and mindfulness were found to be able to achieve those outcomes.19 Online, unidirectional adaptations of these programs similarly offer benefit for women cancer survivors in terms of decreasing sex-related distress and improving mood and sexual function.20 A systematic review of the medical literature supports psychological interventions to address sexual difficulties subsequent to cancer treatment.21

Conclusion

Psychotherapy and specific strategies such as mindfulness and CBT have been studied in various populations of women who have expressed reduced sexual desire causing personal distress with outcomes showing varying degrees of success, including significant improvements in sexual desire and sexual response. An advantage of a psychological treatment approach is that it does not pose a risk of adverse events, and is often far more cost-effective to the approved sexual pharmaceuticals to treat low desire. Psychological treatments can be initiated across populations of women who have low desire regardless of the etiology of those concerns. Moreover, they can simultaneously address and improve other common psychological comorbidities such as stress, anxiety, low mood, and body image concerns.

References

1. Mitchell KR, Mercer CH, Ploubidis GB, Jones KG, et al. Sexual function in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet. 2013 Nov 30;382(9907):1817-29. 2. Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2016 Apr;13(3):538-71 3. American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC. Author. 4. Clayton AH, Goldfischer ER, Goldstein I, Derogatis L, Lewis-D’Agostino DJ, Pyke R. Validation of the decreased sexual desire screener (DSDS). J Sex Med. 2009 Mar;6(3):730-8. 5. McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, et al. Risk factors for Sexual Dysfunction Among Women and Men: A Consensus Statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2016 Feb:13 (2):153-167. 6. Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Nov;112(5):970-8. 7. Bancroft J, Graham CA, Janssen E, Sanders SA. The dual control model: current status and future directions. J Sex Res. 2009 Mar-Jun;46(2-3):121-42. 8. Perelman MA. The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2009 Mar;6(3):629-32. 9. Kingsberg SA. Attitudinal survey of women living with low sexual desire. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2014 Oct;23(10):817-23. 10. Annon JS. The PLISSIT Model: A Proposed Conceptual Scheme for the Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems. J Sex Ed & Ther. 1976;2(1):1-15. 11. Perelman MA. Sex coaching for physicians: combination treatment for patient and partner. Int J Impot Res. 2003 Oct;15 Suppl 5: S67-74. 12. Li-Yun-Fong RJ, Larouche M, Hyakutake M, et al. Is Pelvic Floor Dysfunction an Independent Threat to Sexual Function? A Cross-Sectional Study in Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2017 Feb;14(2):226-237. 13. Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012 Jun;9(6):1497-507. 14. Paterson LQ, Handy AB, Brotto LA. A pilot study of Eight-Session Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Adapted for Women’s Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder. J Sex Res. 2016 Aug 15:1-12. 15. Althof SE. Sex therapy and combined (sex and medical) therapy. J Sex Med. 2011 Jun;8(6):1827-8. 16. Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):230-241. 17. Brotto LA, Chivers ML, Millman RD, Albert A. Mindfulness-Based Sex Therapy Improves Genital-Subjective Arousal Concordance in Women With Sexual Desire. Arch Sex Behav. 2016 Nov;45(8):1907-1921. 18. Brotto LA, Goldmeier D. Mindfulness Interventions for Treating Sexual Dysfunctions: The Gentle Science of Finding Focus in a Multitask World. J Sex Med. 2015 Aug;12(8):1687-9. 19. Brotto LA, Heiman JR, Goff B, et al. A psychoeducational intervention for sexual dysfunction in women with gynecologic cancer. Arch Sex Behav. 2008 Apr;37(2):317-29. 20. Brotto LA, Dunkley CR, Breckon E, et al. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Methods to Evaluate an Online Psychoeducational Program for Sexual Difficulties in Colorectal and Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016 Sep 3:1-18. 21. Brotto LA, Yule M, Breckon E. Psychological interventions for the sexual sequelae of cancer: a review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2010 Dec;4(4):346-60.

Chapter 2: Treatments – Psychology

Atlanta – Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder is a condition that is estimated to affect 10% of adult women.1 Psychological treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness can be employed to treat these women. Clinicians need to recognize cultural or religious factors that influence the patient, as well as mental health conditions that may need to be addressed in women who present with reduced sexual desire.

Show review