Expert Review

5 Most Common Skin Diseases in Primary Care

Chapter 4: Impetigo

Guest Editors

Jaggi Rao, MD, FRCPC

Kaushik Venkatesh, BS

Question & Answer from an Allergist’s Perspective

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

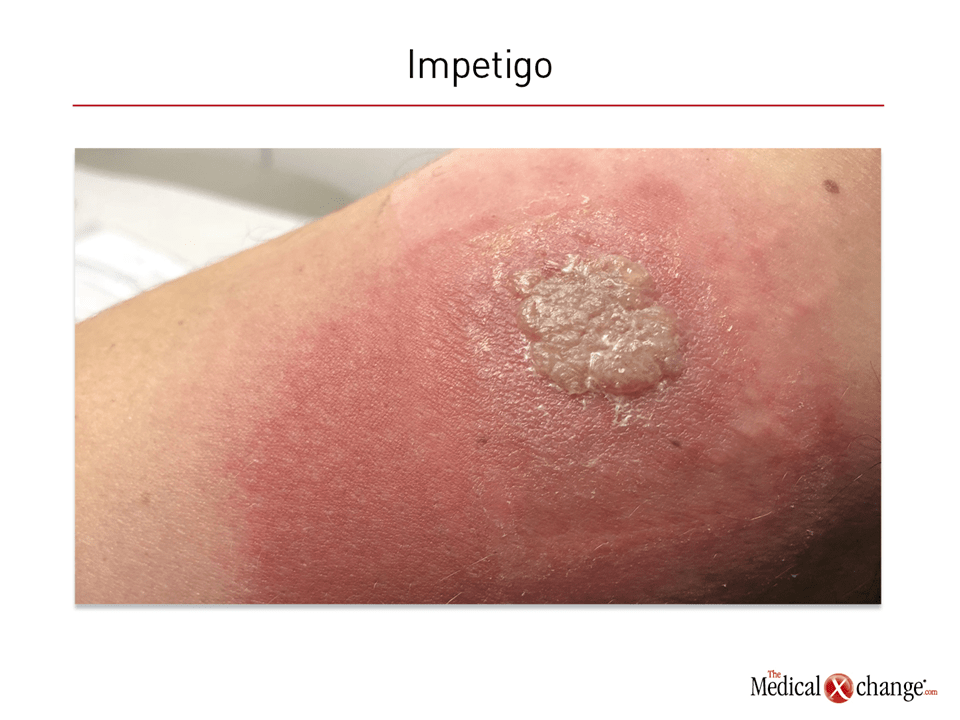

Impetigo is a common bacterial infection of the superficial skin that most commonly occurs among children. Cases in adolescents and adults are commonly observed with some type of skin lesions, such as an abrasion or dermatitis. Non-bullous impetigo, or impetigo contagiosa, is the more common of the two types and is characterized by yellowish crusty lesions. In children, these often include perioral involvement but can appear anywhere on the skin. Bullous impetigo, as the name suggests, is characterized by large, flaccid bullae that are prone to rupture and ooze yellow fluid. These develop most commonly on the trunk, the extremities, or in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla or buttocks.

Impetigo is extremely common in young children, with an average estimated global prevalence of 12.3%. Generally, the prevalence is higher in tropical and low-income areas of the world than in areas with temperate climates, but prevalence rates near 20% have been reported among underprivileged children living in high-income countries, including Canada. Although impetigo readily resolves without scarring even in the absence of treatment, topical antibiotics can speed healing and reduce risk of transmission. In general, systemic involvement and complications are rare, but impetigo caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is potentially serious without prompt intervention.

Pathophysiology

Highly contagious, impetigo is associated with overgrowth of bacteria introduced from the environment which transiently colonize healthy skin. For nonbullous impetigo, Group A streptococcus is the most common pathogen. For bullous impetigo, S. aureus infection accounts for most cases.1,2 There are several risk factors for bacterial overgrowth, including poor hygiene, diminished immune defenses, high temperature or humidity, comorbid dermatoses, and young age. In older individuals, transmission is typically observed only in those with some additional factor compromising the skin barrier function, such as an insect bite or wound, which allows bacterial invasion and overgrowth. In cases where the epidermis is compromised, the condition is known as secondary impetigo.

Nonbullous impetigo, which accounts for approximately 70% of cases,5 is characterized by thin-walled vesicles. The honey-coloured crusting of the nonbullous lesions is produced by the contents of these ruptured vesicles2 (Fig. 1). The lesion formation of the less common bullous impetigo (30% of cases) is attributed to the exfoliative toxins produced by the invading bacteria.6 The pathophysiology of the two subtypes is believed to be similar. In most cases, hygiene plays a role in acquiring and transmitting impetigo.7

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of impetigo is based on clinical examination. Although bacteria are the cause of impetigo, skin swabs are considered unhelpful in diagnosis because they do not reliably distinguish between infectious and resident organisms.8 Based on a probable diagnosis, treatment can be initiated without steps to identify the pathogen. However, if first-line therapy fails, culture of the pus or bullous fluid is a reasonable step to identify the infecting pathogen and its susceptibilities.

The differential diagnosis is specific to the nonbullous and bullous presentations. For nonbullous lesions, the list includes inflammatory conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis, along with other types of infection, including herpes simplex virus, cutaneous candidiasis, and scabies. Of these conditions, scabies, which shares poor hygiene as a risk factor, is the most likely to produce pruritic lesions with a similar distribution and appearance when excoriation has been extensive, but the characteristic mite burrows are pathognomonic.9 For bullous lesions, the list includes various other bullous dermatoses as well as other types of infections or skin wounds, such as insect bites, necrotizing fasciitis, and Stevens’ Johnson syndrome.2

Treatment

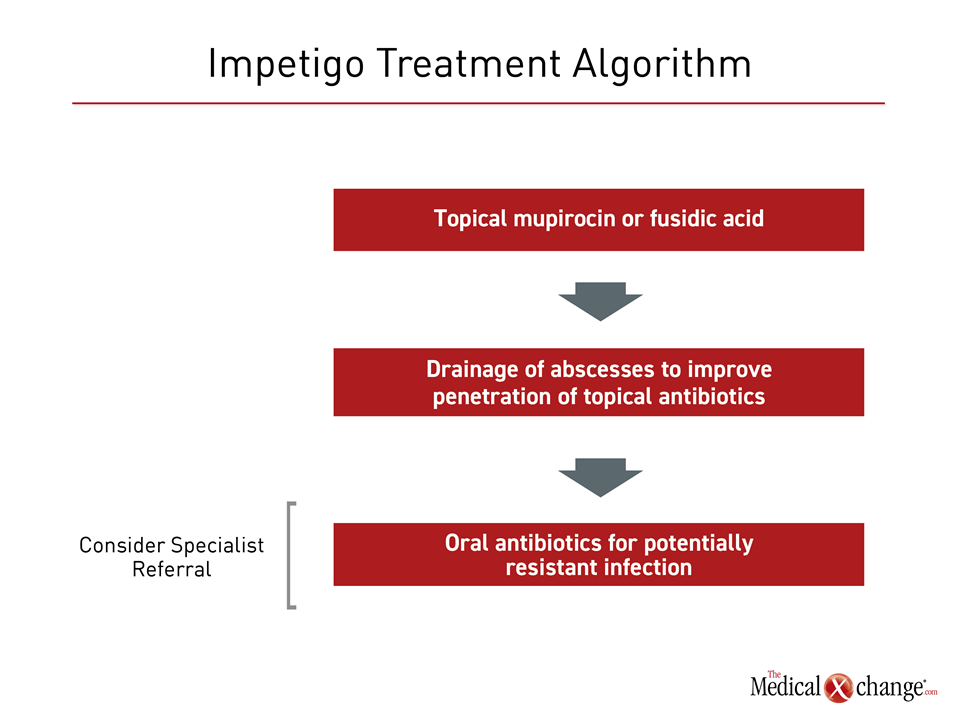

There are no recent guidelines for impetigo management, but the non-profit Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) has published a review of the role of topical antibiotics as first-line therapy.10 Based on a survey of published systematic reviews and meta-analyses, it was concluded that topical mupirocin and fusidic acid are similarly effective in the treatment of impetigo, but that the evidence for the efficacy of bacitracin is insufficient. This review also found topical mupirocin to be at least as effective as erythromycin, dicloxacillin, cephalexin, and ampicillin. A Cochrane Review also concluded that mupirocin and fusidic acid are similarly effective, but more effective than oral antibiotics.11 Although incision and drainage of abscesses is recommended to improve antibiotic penetration in patients with impetigo,12 topical antibiotics have the additional advantage of a low risk of systemic side effects (Fig. 2).

Oral antibiotics appear to be reserved for situations in which topical therapy is impractical or in the event of extensive disease.2 Oral agents or alternatives to first-line topical agents may also be appropriate when the presence of resistant organisms is suspected. Rising rates of MRSA, macrolide-resistant streptococcus, and mupirocin-resistant streptococcus, have been reported.13 In patients who do not respond to first-line antibiotics or who develop fever or other systemic symptoms, agents with relative broad coverage, such as doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), and clindamycin, can be considered.2 All offer at least modest coverage of MRSA, but TMP/SMX has limited efficacy for staphylococcal bacteria. Local antibiotic resistance patterns may be useful for guiding therapeutic decisions when resistance is a concern. Systemic antibiotics may also be used in combination with topical antibiotics for both global and local coverage.

Topical antibiotics, regardless of specific choice, should be applied three times daily for seven to 12 days, but treatment response should be evaluated after three to five days, switching treatments if lesions have not begun to resolve. Oral antibiotics should be offered in their usual doses and schedules for seven days.

Outbreaks of impetigo are common in daycare or other settings where young children are in close contact, and community-acquired MRSA has become widespread in recent years as well.14 Emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis, treatment, and isolation of children with impetigo is an important step for community health professionals for reducing transmission.

Summary

Even though impetigo is a self-limited superficial bacterial infection of the skin in most cases, early diagnosis and treatment facilitate healing and reduce risk of transmission. The nonbullous form of impetigo most commonly involves vesicular lesions with honey-coloured crusts on the face and extremities. It is typically due to overgrowth of S. aureus or S. pyogenes. The less common bullous form of impetigo is more typically caused by streptococcus. In patients with either form, topical antibiotics are the preferred therapy. Oral antibiotics are employed when topical antibiotics are impractical, the disease is extensive, and there is systemic involvement, particularly if an antibiotic-resistant pathogen is suspected.

Impetigo: The Allergist’s Perspective:

Jason K Lee, MD, FRCPC, FAAAAI, FACAAI

Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Internal Medicine

Toronto Allergy and Asthma Clinic

Toronto, Ontario

1. Should impetigo be considered an allergic or dermatologic disease?

Impetigo is caused by bacterial infection. In general, the crusting lesions are not easily confused with pruritic hypersensitivity reactions of the skin. Rather, the differential diagnosis more typically involves other infectious dermatologic diseases, such as herpes. Patients with AD are more at risk for superficial skin infections such as impetigo in general due to a dysregulation of skin immunity.

2. When is it appropriate to refer a patient with impetigo to a specialist?

Topical antibacterial agents are effective for most cases of impetigo, which resolve readily with treatment. Referrals are most appropriate when the diagnosis is uncertain or the lesions do not resolve readily with appropriate treatment.

3. If patients do not respond to first- or second-line treatment for impetigo, what is the most appropriate specialist referral, a dermatologist or an allergist?

Impetigo is an infectious disease readily managed by primary care physicians. Although it is important to consider resistant organisms, including MRSA, in patients who do not respond to first-line therapies, the referral in serious and progressive infections should be made to an infectious disease specialist or a dermatologist or allergist when there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Additional Slide

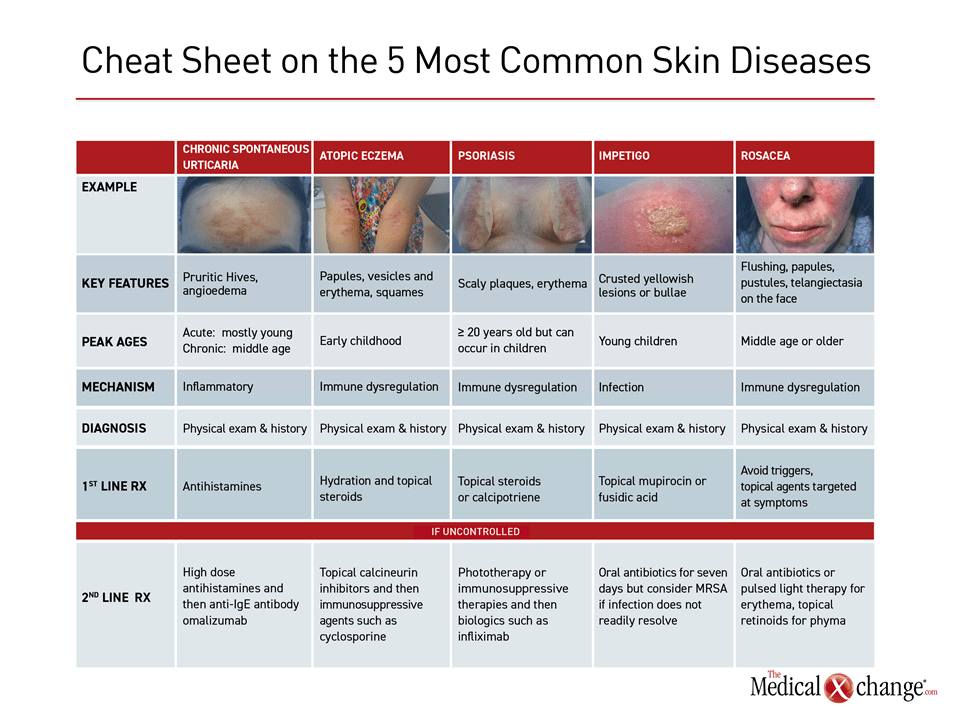

(Fig. 3)References

1. Kosar L, Laubscher T. Management of impetigo and cellulitis: Simple considerations for promoting appropriate antibiotic use in skin infections. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:615-8.

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:229-35.

3. Bowen AC, Mahe A, Hay RJ, et al. The Global Epidemiology of Impetigo: A Systematic Review of the Population Prevalence of Impetigo and Pyoderma. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136789.

4. Peebles E, Morris R, Chafe R. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a pediatric emergency department in Newfoundland and Labrador. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2014;25:13-6.

5. Cole C, Gazewood J. Diagnosis and treatment of impetigo. Am Fam Physician 2007;75:859-64.

6. Amagai M, Yamaguchi T, Hanakawa Y, Nishifuji K, Sugai M, Stanley JR. Staphylococcal exfoliative toxin B specifically cleaves desmoglein 1. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:845-50.

7. Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, et al. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:225-33.

8. George A, Rubin G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of treatments for impetigo. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:480-7.

9. Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A Review of Scabies: An Infestation More than Skin Deep. Dermatology 2019;235:79-90.

10. CADTH. Topical antibiotics for impetigo: a review of the clinical effectiveness and guidelines. https://wwwcadthca/sites/default/files/pdf/htis/2017/RC0851 Topical Antibiotics for Impetigo Finalpdf2017.

11. Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, et al. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD003261.

12. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10-52.

13. Bangert S, Levy M, Hebert AA. Bacterial resistance and impetigo treatment trends: a review. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:243-8.

14. Groner A, Laing-Grayman D, Silverberg NB. Outpatient pediatric community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a polymorphous clinical disease. Cutis 2008;81:115-22.

Chapter 4: Impetigo

Impetigo is a common bacterial infection of the superficial skin that most commonly occurs among children. Cases in adolescents and adults are commonly observed with some type of skin lesions, such as an abrasion or dermatitis. Non-bullous impetigo, or impetigo contagiosa, is the more common of the two types and is characterized by yellowish crusty lesions. In children, these often include perioral involvement but can appear anywhere on the skin. Bullous impetigo, as the name suggests, is characterized by large, flaccid bullae that are prone to rupture and ooze yellow fluid. These develop most commonly on the trunk, the extremities, or in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla or buttocks.

Impetigo is extremely common in young children, with an average estimated global prevalence of 12.3%. Generally, the prevalence is higher in tropical and low-income areas of the world than in areas with temperate climates, but prevalence rates near 20% have been reported among underprivileged children living in high-income countries, including Canada. Although impetigo readily resolves without scarring even in the absence of treatment, topical antibiotics can speed healing and reduce risk of transmission. In general, systemic involvement and complications are rare, but impetigo caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is potentially serious without prompt intervention.

Show review