Expert Review

Severe Asthma: Characterization for Individualized Therapy

Chapter 3: Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: A Clinical Profile

Catherine Lemière, MD, MSc

Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Montreal,

Montreal, Quebec

Eosinophilic asthma has been validated as a clinically relevant phenotype at least in part by the clinical benefit derived from therapies that limit eosinophil activity. Biologics developed for this purpose are currently reserved for patients with severe asthma, a population that by definition is not adequately controlled on standard therapies. As a biomarker for use of biologics in eosinophilic asthma, eosinophilia is a prerequisite, but it is an imperfect predictor of benefit. As asthma is a complex and heterogeneous process, additional biomarkers may further define the patients most likely to respond to agents that downregulate the activity of this pro-inflammatory cell. In the diagnosis and treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma as it is currently defined, treatment with a biologic should be undertaken within a framework of expected benefit, safety and cost. Strategies for patient selection are likely to evolve as additional clinical data become available.

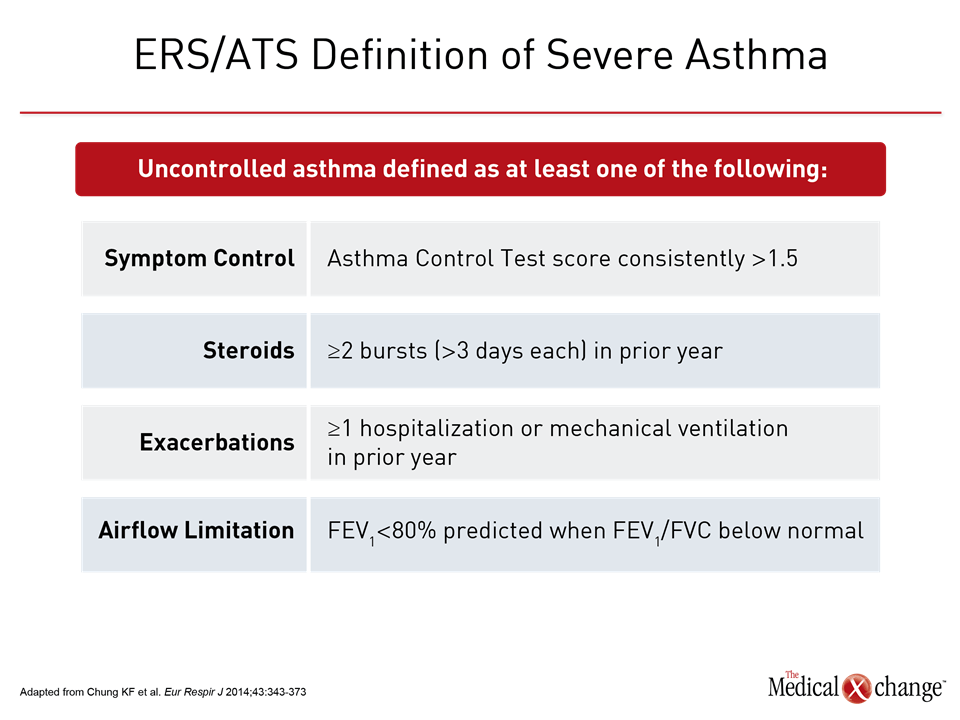

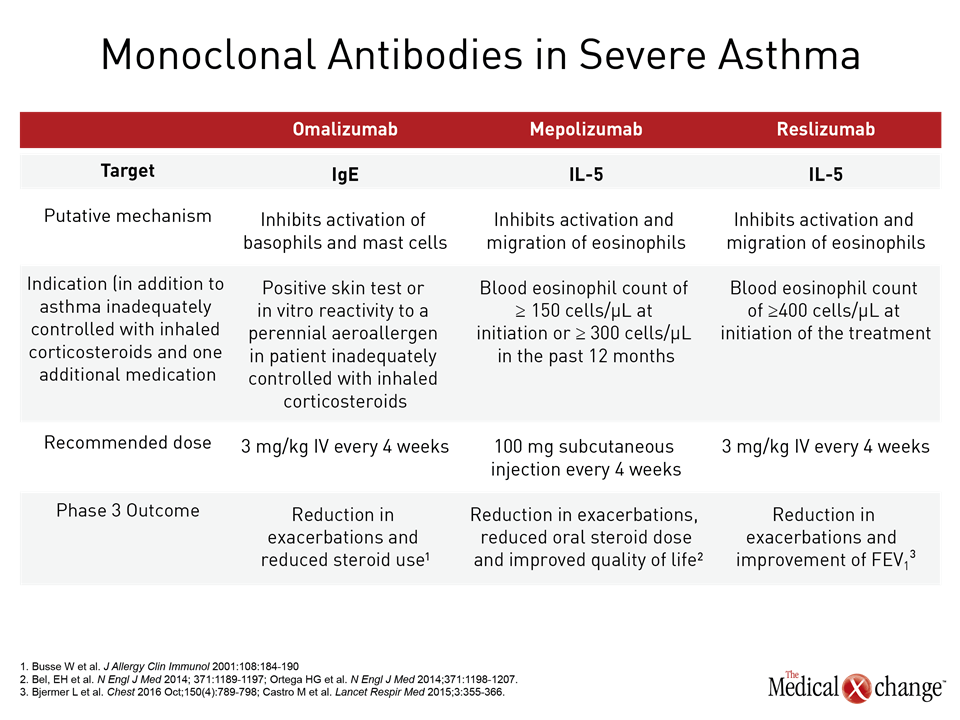

The Severe Eosinophilic Asthma Phenotype

Asthma is considered severe when symptom control remains poor despite standard therapy that includes high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in addition to another controller or when control is lost when high doses of ICS or systemic corticosteroids are tapered1 (Table 1). This definition excludes patients with symptoms difficult to control for reasons unrelated to treatment efficacy, such as lack of adherence to treatment or poor inhaler technique. Before a patient is characterized as having severe asthma, it is expected that these confounders have already been evaluated and addressed. Among strategies to individualize therapy for patients with severe asthma, phenotyping has practical value as a result of the introduction of biologics that target molecular pathways associated with disease progression in these phenotypes.2 Omalizumab, which targets IgE, was the first of the biologics introduced to target a severe asthma phenotype. The labeling in Canada restricts use of omalizumab to patients with a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen, which is characteristic of the allergic asthma phenotype. Subsequently, the introduction of biologics targeting interleukin-5 (IL-5), an important mediator of eosinophil proliferation, has provided an option for treating severe asthma of the eosinophilic phenotype. Like omalizumab, the two available anti-IL-5 therapies, mepolizumab and reslizumab, have been approved as add-on maintenance in patients with asthma not adequately controlled with standard therapies. For these biologics, the labeling further requires eosinophilia (Table 2). In severe asthma, these biologics has introduced phenotyping as a strategy for personalizing therapy. Prior to phenotyping in order to consider a biologic therapy, it is appropriate to optimize standard therapies and to evaluate and treat the comorbidities that may be exacerbating symptoms. The lack of eosinophilia is associated with a lack of efficacy of these molecules. Presence of eosinophilia identifies patients with an increased likelihood of benefiting from an anti-IL-5 biologic, but responses remain variable. Biologics have a high acquisition cost. Relative to inhaled or oral therapies, the available products require subcutaneous (SQ) or intravenous (IV) administration, which many patients may find inconvenient. As a result, these therapies are not first-line even among those with poorly controlled symptoms and elevated blood or sputum eosinophil counts. Judicious application is appropriate.

Features of Eosinophilic Asthma Phenotype

The eosinophilic asthma phenotype is derived from an even more basic division involving type 2 T-helper (Th2) inflammation. Th2-high asthma describes upregulation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which in turn are associated with immune responses mediated by eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils.3 Th2-low asthma, which is encountered less commonly and is less well described, has been differentiated from Th2-high asthma with several measures, including gene expression,4 although there is no standard biomarker for this subtype.5 More closely associated with upregulation of neutrophils, Th2-low asthma appears to be less closely associated with inflammation or allergic response. The effort to understand the underlying mediators of this phenotype are on-going.6 Further subgrouping of both Th-2-high and Th2-low by phenotype is likely to be relevant to treatment selection, but the eosinophilic phenotype, a subcategory of Th2-high asthma, has gained relevance as a result of biologics that target IL-5. Although other cytokines are associated with eosinophil activity, IL-5 is implicated in differentiation and maturation of eosinophils in the bone marrow, stimulation of eosinophil migration from the blood to tissue sites, and inhibition of eosinophil apoptosis.7 Inhibition of IL-5 or the IL-5 receptor alpha, which is highly expressed on the eosinophil,8 is associated with a marked decrease in blood and sputum eosinophilia. The clinical trials with anti-IL-5 biologics validate eosinophils as a target in severe asthma, although they further show that eosinophilia is a necessary but not a sufficient predictor of response. In patients with elevated eosinophils but a modest or no response to anti-IL-5 therapies despite large reductions in eosinophilia, it is likely that other or additional mediators of the airway inflammation are active.

Biologics in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: Clinical Trials

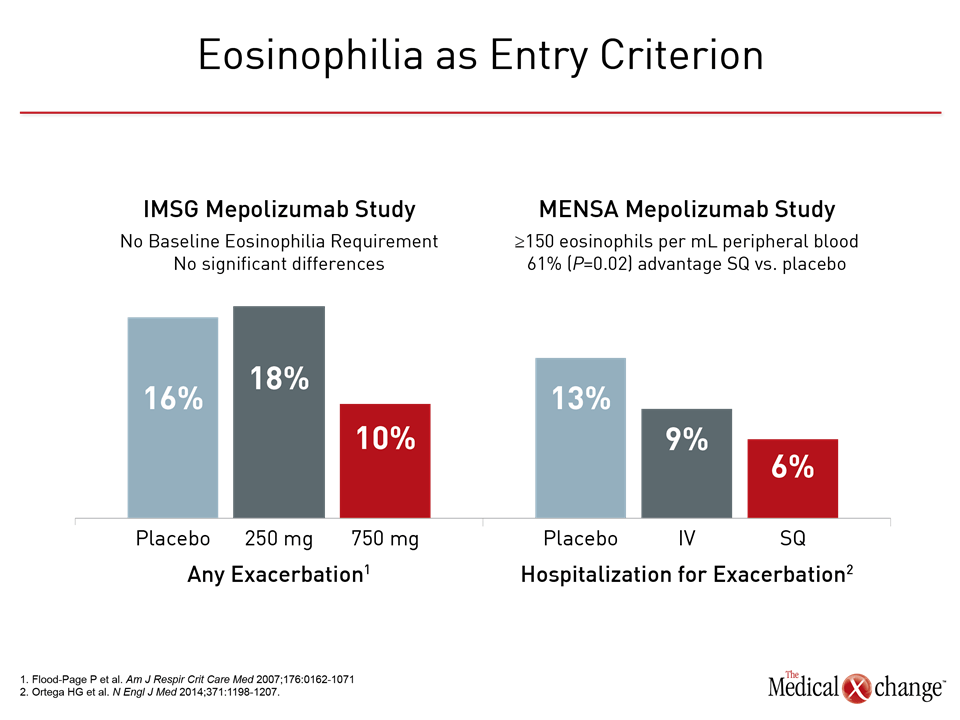

The initial clinical trials with anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies, often conducted in patients with persistent but moderate asthma but who were not required to have eosinophilia at entry, were disappointing. In a double-blind by the International Mepolizumab Study Group (IMSG), mepolizumab was not associated with a significant impact on any outcome measure, including lung function, despite significant reductions in blood and sputum eosinophils from baseline.9 In a study conducted with reslizumab, the dose-dependent reduction in eosinophils was associated with only a trend toward improved lung function and no significant impact on other indices of disease activity.10 When eosinophilia was required for entry in subsequent trials, benefits became clinically meaningful. In MENSA, a phase 3 trial with mepolizumab, the rate of exacerbations was reduced by 53% (P<0.001) for the more effective of two tested doses.11 When compared to the earlier IMSG study, MENSA was largely confirmatory of the importance of baseline eosinophilia (Fig. 1). In BREATH, a phase 3 trial with reslizumab, and CALIMA, a phase 3 trial with the experimental IL-5 receptor alpha agent benralizumab, the reductions in the annualized rate of exacerbations on the most effective dose regimens were 59% (P<0.001) and 70% (P<0.001), respectively.12,13 These findings provided the basis for the mepolizumab and reslizumab labeling that specifies the presence of blood eosinophilia within the indication for treatment. In theory, sputum eosinophil thresholds could be a more representative indication of the activity of airway eosinophilia, but these are not listed in the labeling. Since clinical trials on anti-IL-5 therapies have not used sputum eosinophil counts prospectively in a large number of subjects, the optimal sputum eosinophil count cut-off for predicting a clinical response to anti-IL5 therapies is unknown. Furthermore, this test is not available in a majority of centres. As outlined by the authors of ERS/ATS guidelines on severe asthma and others, the availability of biologics has provided an impetus to pursue additional biomarkers with the potential to personalize therapy. Although the accuracy of laboratory and clinical predictors of response to targeted therapies remain limited, more than 100 inflammatory mediators have been implicated in asthma pathogenesis,14 and individual variability in the relative role of these mediators in specific patients may explain the variability of response to specific targeted therapies. The development of therapies targeted at additional inflammatory mediators may provide new information about how other cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, as well chemokines and growth factors contribute the pathogenesis of asthma at the same time that they provide new opportunities for disease control.

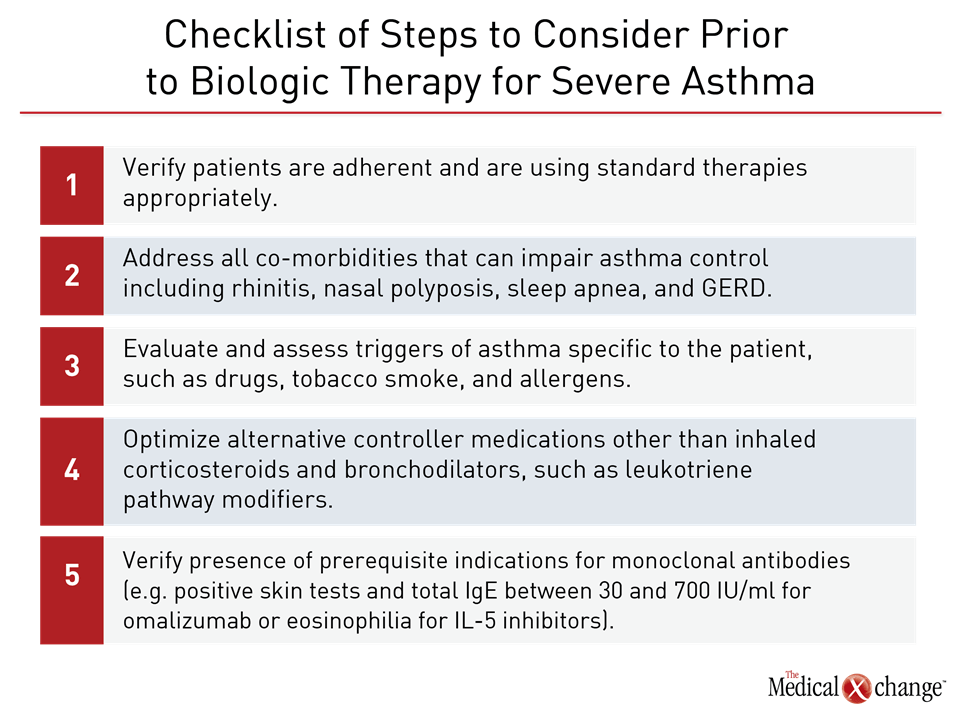

Biologics in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: Practical Strategies

Asthma is a complex process with a heterogeneous presentation. Comorbidities are common and may affect disease control. In the effort to establish severe disease, it is appropriate to take specific steps to ensure that patients are employing standard therapies appropriately prior to considering a biologic even among those who meet criteria for severe eosinophilic asthma. Comorbidities such as rhinitis, nasal polyposis, sleep apnea, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are among treatable conditions that accompany asthma and may exacerbate airway impairment. Some drugs, such as beta blockers, may activate symptoms consistent with asthma, while smoking is a prominent and reversible cause of airway impairment. Environmental triggers of respiratory symptoms should also be evaluated and addressed before declaring that standard therapies are unable to provide adequate symptom control (Table 3). In patients with persistence of the severe eosinophilic asthma phenotype despite optimized use of inhaled therapies and leukotriene pathway modifiers, a trial of an anti-IL-5 biologics is reasonable. Choice of agent may be best guided by considerations such as cost or convenience. There are no head-to-head comparisons between mepolizumab and reslizumab or these approved agents and benralizumab, the only other anti-IL-5 therapy to have completed phase 3 trials. Mepolizumab, which is administered SQ, and reslizumab, which is administered IV, bind to IL-5 to inhibit its activity. Benralizumab binds to the IL-5 receptor alpha. In a recent meta-analysis of randomized trials, there were no significant differences in clinical benefits between agents that inhibit the IL-5 pathway. This analysis did suggest a slight advantage in mean treatment effects for patients with a baseline serum eosinophilia of >300 eosinophils per mm3/L relative to those with fewer eosinophils, but benefit at lower eosinophil counts is well documented. As recommended in the ERS/ATS guidelines, the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma may be best relegated at the current time to centers familiar with phenotyping, strategies for evaluating eosinophilia, and the assessment of response. In the absence of reliable methods for predicting benefit, treatment of this phenotype, once eosinophilia is established, remains to a large degree empirical. Anti-IL-5 antibodies are an important option for improving control, including reducing the rate of exacerbations, but these therapies, in part due to their expense, should be reserved for those who cannot be controlled on simpler and less costly strategies. One of the most important contributions of highly targeted therapies is the proof they provide that the underlying drivers of severe asthma are not identical. It is likely that strategies to improve patient selection will emerge from ongoing and future studies. Agents with highly targeted effect on specific pathways of inflammation raise the possibility of reversing not just controlling asthma. By downregulating the inflammatory component of asthma at an early stage of disease, there may be an opportunity to alter the pathophysiology that underlies asthma chronicity. Although clinical trials exploring this potential have yet to be conducted, progress in identifying important mediators of asthma pathophysiology support the effort to pursue treatments that may address the underlying pathways of disease, shifting a focus that has been largely directed to managing symptoms.

Conclusion

In patients with severe asthma, phenotyping has been rendered relevant by the introduction of biologics. Although the eosinophilia characteristic of the eosinophilic phenotype is necessary but not sufficient for considering biologic therapies, anti-IL-5 therapies can improve control in a group of patients who have traditionally had limited treatment options. A trial of these agents is appropriate as an adjunct to standard therapies after standard therapies have been optimized. Due to variability in response, benefit should be monitored.

References

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343-73.

- Papathanassiou E, Loukides S, Bakakos P. Severe asthma: anti-IgE or anti-IL-5? Eur Clin Respir J 2016;3:31813.

- Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:388-95.

- Sterk PJ, Lutter R. Asthma phenotyping: TH2-high, TH2-low, and beyond. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:395-6.

- Robinson D, Humbert M, Buhl R, et al. Revisiting Type 2-high and Type 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:161-75.

- Fahy JV. Asthma Was Talking, But We Weren’t Listening. Missed or Ignored Signals That Have Slowed Treatment Progress. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13 Suppl 1:S78-82.

- Varricchi G, Bagnasco D, Borriello F, Heffler E, Canonica GW. Interleukin-5 pathway inhibition in the treatment of eosinophilic respiratory disorders: evidence and unmet needs. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;16:186-200.

- Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:1344-53 e2.

- Flood-Page P, Swenson C, Faiferman I, et al. A study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:1062-71.

- Kips JC, O’Connor BJ, Langley SJ, et al. Effect of SCH55700, a humanized anti-human interleukin-5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1655-9.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1198-207.

- Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:355-66.

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2128-41.

- Adcock IM, Caramori G, Chung KF. New targets for drug development in asthma. Lancet 2008;372:1073-87.

- Cabon Y, Molinari N, Marin G, et al. Comparison of anti-interleukin-5 therapies in patients with severe asthma: global and indirect meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:129-38.

Chapter 3: Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: A Clinical Profile

Eosinophilic asthma has been validated as a clinically relevant phenotype at least in part by the clinical benefit derived from therapies that limit eosinophil activity. Biologics developed for this purpose are currently reserved for patients with severe asthma, a population that by definition is not adequately controlled on standard therapies. As a biomarker for use of biologics in eosinophilic asthma, eosinophilia is a prerequisite, but it is an imperfect predictor of benefit. As asthma is a complex and heterogeneous process, additional biomarkers may further define the patients most likely to respond to agents that downregulate the activity of this pro-inflammatory cell. In the diagnosis and treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma as it is currently defined, treatment with a biologic should be undertaken within a framework of expected benefit, safety and cost. Strategies for patient selection are likely to evolve as additional clinical data become available.

Show review