Expert Review

The Aging HIV Patient

Chapter 3: Renal Impairment

Derek M. Fine, MD

Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a significant threat to the long-term survival of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) dramatically reduced the risk of end stage renal disease (ESRD) from HIV-specific causes, as it did many of the other complications of uncontrolled HIV, it attenuated but did not eliminate the development of compromised renal function from causes indirectly related to HIV infection. Until recently, the risk of renal failure as a complication of HIV has been concentrated in African-Americans, who have demonstrated an increased susceptibility to HIV-associated nephropathy, but the incidence of renal impairment in aging individuals with otherwise well-controlled HIV infection is climbing. In the setting of HIV infection, therapies traditionally employed to preserve renal function, such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, are appropriate, but other steps should be considered. This may include preferential use of antiretroviral agents with the least potential to exacerbate renal dysfunction. Close monitoring of renal function is appropriate because of variability in the individual risk for renal disease and progression of nephropathy once it is established.

Background

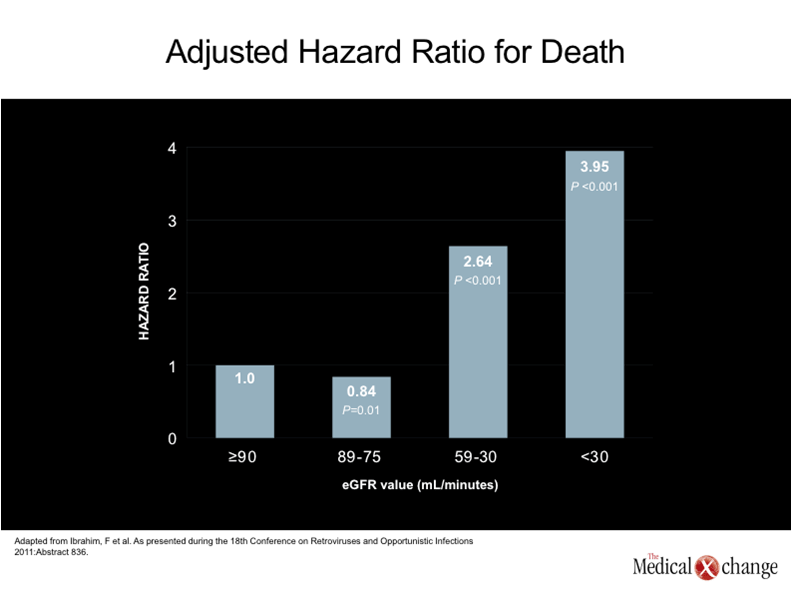

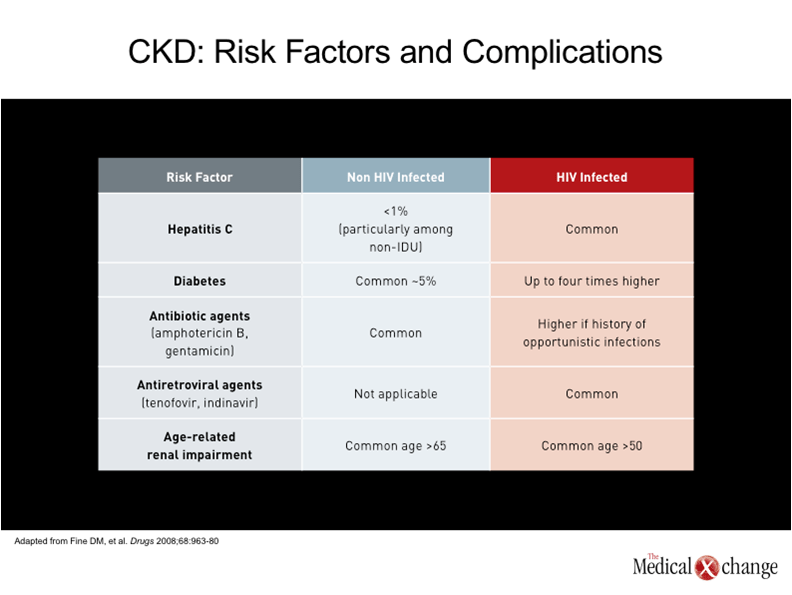

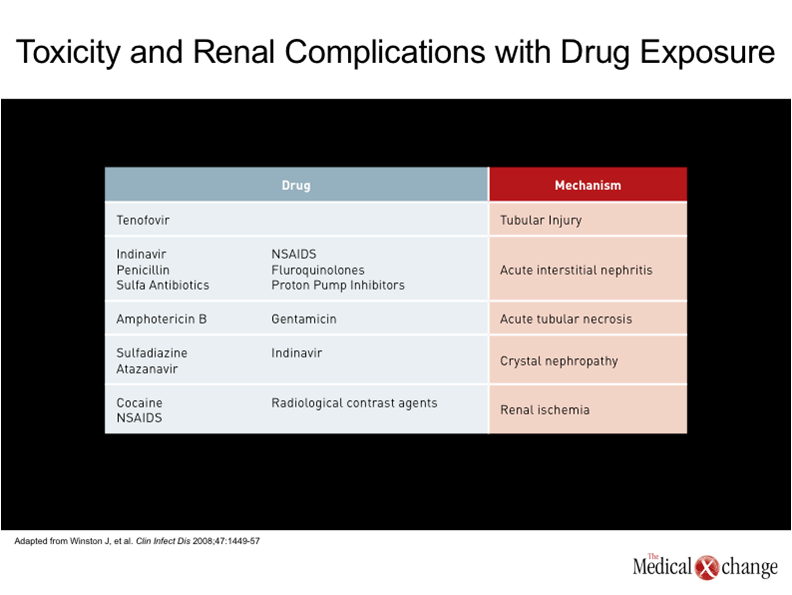

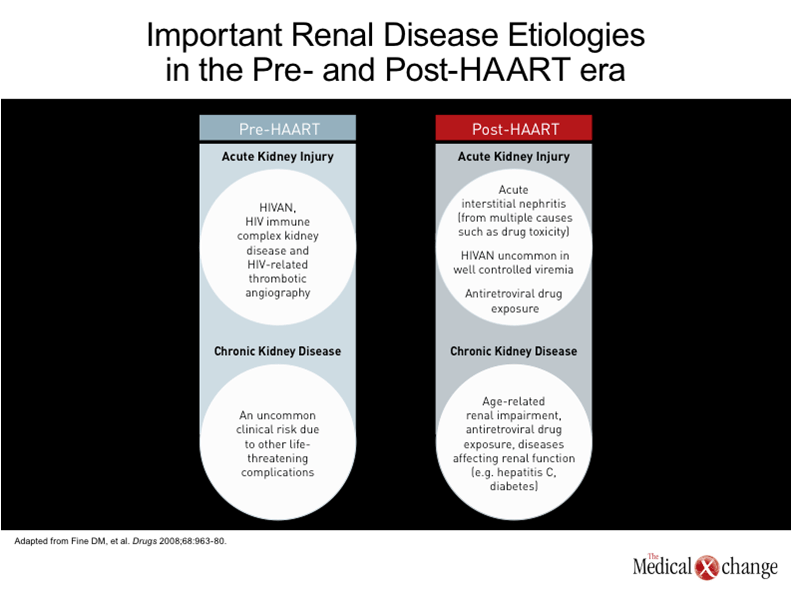

One of the earliest descriptions of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), published in 1984, described a focal segmental glomerulosclerosis of unclear aetiology.(1)In the subsequent period leading up to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), HIVAN was recognized as a major cause of HIV-related mortality, particularly among those of Black race.(2)The condition was frequently accompanied by severe proteinuria, and acute kidney injury (AKI) leading rapidly to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and death.(3) In the HAART era, the risk of ESRD in HIV patients has diminished substantially in both Blacks and Whites.(4-5)Individuals of African descent, however, still remain at greater risk for HIVAN and other forms of kidney disease.(6)This is attributed to a large extent to a genetic susceptibility created by variants of the APOL1 gene on chromosome 22,(7)which are uniformly present in those with HIVAN, a histopathological entity distinct from other forms of CKD that is best confirmed with biopsy. The variants, or polymorphisms, also appear to explain the increased risk of ESRD in HIV-negative Blacks relative to HIV-negative Whites,(8), and may explain the far more rapid deterioration of renal function in HIV-positive Blacks when compared to HIV-positive Whites.(5)There have been no randomized trials to confirm the ability of HAART to prevent HIVAN, but retrospective analyses indicate that HIVAN is an uncommon complication in patients who begin HAART prior to severe immune deficiency and who maintain a HIV viral load <400 copies/mL.(9)HIVAN is now generally confined to patients who reach an advanced stage of immunodeficiency before antiretroviral therapy is initiated, but current treatment strategies, as discussed below, may prevent progression to ESRD. In those evolving to ESRD kidney transplantation may allow a dialysis free, long term survival.(10) Despite the diminished likelihood of HIVAN in the HAART era, the risk of renal disease in patients with HIV infection is expected to increase in aging HIV-infected individuals for a number of reasons. The presence of microalbuminuria, a precursor to more severe renal disease, is up to five-times higher than in non-HIV controls after multivariate adjustment.(11)Unlike HIVAN, renal disease in the era of HAART is associated with indolent rather than acute pathological processes, even though, ultimately, it may be no less life-threatening. In the assessment of renal function obtained in 20,132 HIV-infected patients, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the post-HAART era was a strong predictor of mortality.(12) (Fig. 1). This is not surprising due to the numerous studies in the non-HIV infected showing similar outcomes. In the growing literature documenting acceleration of age-related processes, the kidney can be both directly and indirectly affected (13). For example, type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is a major risk factor for renal impairment, is four times more prevalent in patients with HIV relative to an age-matched population. (14)The prevalence of hypertension, another risk factor for renal impairment, is up to three times higher.(15)Hepatitis C virus (HCV), which can also impair renal function, is far more common in individuals with HIV than in those who are not infected.(16) In addition, it is now clear that several antiretroviral therapies also increase the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Often, the relative increase in risk is subtle, but antiretroviral therapies must be taken indefinitely, possibly producing risk from a cumulative effect. Although there may be no goal more important in the treatment of HIV than sustaining a low viral load, selecting an agent that poses a low risk of renal impairment may be particularly important to those who already have risk factors for renal disease or established renal impairment.(17) For the clinician, it is important to recognize the growing problem of CKD in aging individuals with HIV infection and to consider a broad range of presentations and aetiologies.(18)Importantly, many of these aetiologies are the same as those encountered in a non-HIV-infected population but occur at a younger age with a greater propensity for life-threatening complications over a shorter period of time. (Table 1). The HIVAN of the pre-HAART era and the CKD common to aging individuals with controlled HIV infection are generated by very different pathological events. HIVAN has been attributed to localized HIV infection of renal glomerular and tubular epithelial cells, which produces glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial scarring.(19-20)HIV infection of renal epithelial cells thereby drives impairment of glomerular filtration by directly disturbing cell functions. HIV-specific immune complex glomerulonephritis and HIV-related thrombotic microangiopathy, which do not occur more frequently in Blacks, are less common renal diseases associated HIV.(7) To understand the recent and ongoing growth of renal disease in individuals with HIV infection, it is important to recognize that CKD is a common condition in the absence of HIV infection, and that overall rates are increasing. Likely to be at least partly due to the growing problem of obesity and its associated pathology, particularly diabetes,(21)the rising rates of CKD may also be attributed to the demographic shift that is increasing the median age in Canada and elsewhere.(22)Similar trends, particularly the aging of individuals with HIV, explain the rising rate of CKD in individuals infected with HIV. However, the HIV population has additional risks, which not only include a high prevalence of diseases that may adversely affect renal function, such as hepatitis C infection, but a relatively high risk of exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, which includes antiretrovirals, illicit drugs such as cocaine, as well as antibiotics such as gentamicin and amphotericin.(23). Patients with HIV infection may not have any greater risk of exposure to other agents associated with nephrotoxicity, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but they may be more likely to develop renal complications, including acute interstitial nephritis, as a result of the large number of drugs to which they are exposed.(24) Isolated cases of AKI have been reported for essentially all antiretroviral agents, but the two agents most consistently linked with acute and chronic renal effects are the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) tenofovir and the protease inhibitor (PI) indinavir.(6)Overall, the risk of AKI and CKD is low on tenofovir among young and relatively healthy patients (25), but this agent may induce proximal renal tubule damage that may pose increasing risk for kidney injury in patients with other risk factors. The risk of damage to the kidney from tenofovir is likely to be increased in those who already have CKD and those with prolonged exposure.(26)In one retrospective analysis of 10,000 patients exposed to tenofovir, nephrotoxicity was identified in only 2% of patients, but the risk of demonstrating a rise in serum creatinine of >0.5 mg/dL (44.2 µmol/L) was increased by an elevated baseline serum creatinine, concomitant use of another nephrotoxic agent, and older age.(27)The risk posed by indinavir, unlike tenofovir, appears to stem from chronic interstitial nephritis,(28)but this protease inhibitor is rarely used in the current era and so does not contribute substantially to current risk. (Table 2).

Clinical Features and Evaluation of Renal Disease in HIV Patients

In the post-HAART era, HIVAN should not be overlooked as a potential complication of HIV, particularly in individuals of African descent not virally suppressed on antiretroviral medication. HIVAN typically presents with a high level of proteinuria, which is often but not always nephrotic, and rapidly progressive acute kidney failure (3). HIVAN, which is not typically associated with hypertension or oedema, is generally observed in HIV-infected patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or who otherwise have a low CD4 count and high viral loads. However, most renal disease in HIV-infected individuals is now due to aetiologies either indirectly related to HIV infection, such as antiretroviral therapies, or to processes that may be exacerbated but not caused by HIV infection. Many of these aetiologies are generally shared with a non-HIV-infected population, but the onset may be earlier or complicated by concomitant diseases, such as HCV infection. It is helpful when reaching a diagnosis to distinguish between AKI, which represents rapid renal impairment, and CKD, which, although more slowly progressive, is generally irreversible even if further progression can be attenuated (Fig. 2). Whether nephropathy is due to immune-related glomerulonephritis or progressive renal insufficiency due to other pathologic processes, including age-related decline in function or drug-induced renal damage, the early stages are likely to be clinically silent detectable only by laboratory testing. It is therefore appropriate to include renal function assessments within routine evaluation of HIV-infected patients, including those who are otherwise well with good infection control.(29) Proteinuria typically provides the earliest signal of renal disease in those diseases that manifest with proteinuria (generally diseases with glomerular involvement).(30)Up to one-third of patients with HIV will demonstrate abnormal kidney function on the basis of elevated protein in the urine.(31)Although not all have a level that requires therapy, proteinuria is often associated with progressive renal disease, suggesting the need for close observation in such patients. Proteinuria, even in the microalbuminuria range (30 to 300 mg/24 hours) is an adverse prognostic sign, predicting increased health risks, including CV events. Although a 24-hour urine collection is generally considered the most accurate method for assessing proteinuria, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) accepts a urine dipstick as a screening tool in guidelines for monitoring renal function in HIV patients. However, a protein-to-creatinine ratio on a single urine sample, commonly referred to as a spot test, provides a more accurate assessment of proteinuria with reasonable convenience. Regardless of the degree of proteinuria, an eGFR analysis (with the use of creatinine based formulas) is warranted to evaluate renal function in all patients upon initial presentation. The accepted diagnosis of CKD is eGFR <60 ml/min/173m2 persisting for at least three months or the presence of another kidney abnormality, such as proteinuria, for more than 3 months regardless of eGFR .(32)The decision regarding how often to perform repeated eGFR assessments should be influenced by the degree of proteinuria and the presence of risk factors for CKD, the presence of diabetes or other co-morbidities, exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, smoking, dyslipidemia, or use of intravenous drugs.(29) In young otherwise healthy individuals with good control of HIV infection and no risk factors for renal disease, routine monitoring of renal function can be reserved for periodic health assessments, but the frequency of monitoring and the types of monitoring should be intensified with increasing age and increasing number of risk factors. While dipstick urine measurements of proteinuria may be adequate in low-risk patients, concern about the potential presence of renal disease should prompt additional measures, including protein-to-creatine or albumin-to-creatine assessments and eGFR, when risk is high or the presence of proteinuria suggests a more thorough evaluation. In HIV-infected patients, renal biopsy may be required for a definitive diagnosis of the aetiology AKI or CKD, including HIVAN. In patients with AKI, particularly those suspected of HIVAN, a kidney biopsy should be conducted promptly because of the rapid deterioration in renal function associated with this condition. One of the most common alternative causes of AKI in patients with HIV is acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), which, like HIVAN, may have characteristic features that facilitate diagnosis on biopsy. In patients with CKD, biopsy may not be necessary if the decline in renal function is consistent with a concomitant disease, such as diabetes. However, biopsy may be useful for evaluating renal involvement in patients with HCV when attempting to identify the best management strategy. In patients with multiple diagnostic possibilities, biopsy is particularly useful in guiding management.

Treatment

In many cases, nephropathy cannot be reversed but the progression can be slowed substantially. The first step is to modify or eliminate potential sources of nephropathy or nephrotoxicity. This may include treating hepatitis C or switching to HAART regimens that do not include tenofovir. Early detection of declining renal function may provide an opportunity to intervene when renal damage is limited, particularly if the aetiology can be identified. With tenofovir use, for example, the immediate risk of clinically significant renal disease appears to be low in the context of slowly declining renal function, but the adverse consequences of long-term treatment may be cumulative or increased in the presence of additional risk factors for CKD.(33) For patients with HIVAN or HIV immune complex renal disease, who have not yet started antiretroviral therapy, suppression of the viral load is the most important immediate step. Steroids may also be of benefit during the acute presentation of HIVAN. After the acute phase, progression of renal impairment may be attenuated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.(34)Care of HIVAN (or any other kidney disease) that has advanced to ESRD or has a high likelihood of advancing to ESRD should be directed by nephrologists who can provide dialysis and who have access to sophisticated therapeutic options, such as organ transplant. In patients with CKD, the same principles for preserving kidney function in individuals who are HIV-negative apply for those with HIV infection. This includes strict blood pressure control and glucose control (in diabetics), control of dyslipidemias, avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, and adequate doses of ACE inhibitors or other inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system. Avoiding smoking and low levels of alcohol ingestion are also prudent. Due to the association of renal dysfunction with abnormal bone metabolism and anemia, these potential problems should be monitored.

Conclusion

HIV infection has been a risk factor for renal dysfunction and progression to ESRD from the earliest stages of the epidemic. Although the introduction of HAART greatly modified the risk for HIVAN, rates of renal disease are expected to climb faster in an aging HIV population even when their infection is well controlled when compared to individuals of similar age without HIV. There are numerous reasons to anticipate high rates of CKD in aging patients with HIV, including a greater number of risk factors, higher exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, and what appears to be a more rapid aging process in HIV-infected individuals. While screening for renal function should be included in routine health assessments in individuals with HIV as in individuals who are not infected with HIV, more frequent and more rigorous screening is warranted in this population.

References

1. Rao TK, Filippone EJ, Nicastri AD, et al. Associated focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1984;310(11):669-73. 2. Winston JA, Klotman PE. Are we missing an epidemic of HIV-associated nephropathy? J Am Soc Nephrol 1996;7(1):1-7. 3. Carbone L, D’Agati V, Cheng JT, Appel GB. Course and prognosis of human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. Am J Med 1989;87(4):389-95. 4. Ahuja TS, Grady J, Khan S. Changing trends in the survival of dialysis patients with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13(7):1889-93. 5. Lucas GM, Lau B, Atta MG, Fine DM, Keruly J, Moore RD. Chronic kidney disease incidence, and progression to end-stage renal disease, in HIV-infected individuals: a tale of two races. J Infect Dis 2008;197(11):1548-57. 6. Winston J, Deray G, Hawkins T, Szczech L, Wyatt C, Young B. Kidney disease in patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47(11):1449-57. 7. Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 2010;329(5993):841-5. 8. Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, Bertenthal D, Volberding PA, O’Hare AM. Racial differences in end-stage renal disease rates in HIV infection versus diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol2007;18(11):2968-74. 9. Estrella M, Fine DM, Gallant JE, et al. HIV type 1 RNA level as a clinical indicator of renal pathology in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43(3):377-80. 10. Stock PG, Barin B, Murphy B, et al. Outcomes of kidney transplantation in HIV-infected recipients. N Engl J Med 2010;363(21):2004-14. 11. Szczech LA, Grunfeld C, Scherzer R, et al. Microalbuminuria in HIV infection. AIDS 2007;21(8):1003-9. 12. Ibrahim F, Hamzh L, Jones R, Nitsch D, Sabin C, Post F. Renal disease: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2011:Abstract 836. 13. Vance DE, Mugavero M, Willig J, Raper JL, Saag MS. Aging with HIV: a cross-sectional study of comorbidity prevalence and clinical characteristics across decades of life. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2011;22(1):17-25. 14. Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(10):1179-84. 15. Gazzaruso C, Bruno R, Garzaniti A, et al. Hypertension among HIV patients: prevalence and relationships to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2003;21(7):1377-82. 16. Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis C: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21 Suppl C:25C-34C. 17. Hawkins T. Understanding and managing the adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Antiviral Res 2010;85(1):201-9. 18. Rachakonda AK, Kimmel PL. CKD in HIV-infected patients other than HIV-associated nephropathy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010;17(1):83-93. 19. Marras D, Bruggeman LA, Gao F, et al. Replication and compartmentalization of HIV-1 in kidney epithelium of patients with HIV-associated nephropathy. Nat Med 2002;8(5):522-6. 20. Alpers CE, Kowalewska J. Emerging paradigms in the renal pathology of viral diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2 Suppl 1:S6-12. 21. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27(5):1047-53. 22. Levin A, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease. CMAJ 2008;179(11):1154-62. 23. Fine DM, Perazella MA, Lucas GM, Atta MG. Renal disease in patients with HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Drugs 2008;68(7):963-80. 24. Parkhie SM, Fine DM, Lucas GM, Atta MG. Characteristics of patients with HIV and biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5(5):798-804. 25. Izzedine H, Hulot JS, Vittecoq D, et al. Long-term renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients. Data from a double-blind randomized active-controlled multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20(4):743-6. 26. Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 2010;24(11):1667-78. 27. Nelson MR, Katlama C, Montaner JS, et al. The safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of HIV infection in adults: the first 4 years. AIDS 2007;21(10):1273-81. 28. Berns JS, Kasbekar N. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and the kidney: an update on antiretroviral medications for nephrologists. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;1(1):117-29. 29. Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(11):1559-85. 30. Estrella MM, Fine DM. Screening for chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010;17(1):26-35. 31. Gupta SK, Mamlin BW, Johnson CS, Dollins MD, Topf JM, Dube MP. Prevalence of proteinuria and the development of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients. Clin Nephrol 2004;61(1):1-6. 32. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139(2):137-47. 33. Rodriguez-Novoa S, Alvarez E, Labarga P, Soriano V. Renal toxicity associated with tenofovir use. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2010;9(4):545-59. 34. Wei A, Burns GC, Williams BA, Mohammed NB, Visintainer P, Sivak SL. Long-term renal survival in HIV-associated nephropathy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Kidney Int 2003;64(4):1462-71.

Chapter 3: Renal Impairment

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a significant threat to the long-term survival of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) dramatically reduced the risk of end stage renal disease (ESRD) from HIV-specific causes, as it did many of the other complications of uncontrolled HIV, it attenuated but did not eliminate the development of compromised renal function from causes indirectly related to HIV infection. Until recently, the risk of renal failure as a complication of HIV has been concentrated in African-Americans, who have demonstrated an increased susceptibility to HIV-associated nephropathy, but the incidence of renal impairment in aging individuals with otherwise well-controlled HIV infection is climbing. In the setting of HIV infection, therapies traditionally employed to preserve renal function, such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, are appropriate, but other steps should be considered. This may include preferential use of antiretroviral agents with the least potential to exacerbate renal dysfunction. Close monitoring of renal function is appropriate because of variability in the individual risk for renal disease and progression of nephropathy once it is established.

Show review