Expert Review

Unmet Needs in PPI Therapy for GERD

Chapter 3: GERD – The Era of PPIs

Brian Bressler, MD, MS, FRCPC

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) replaced previous options for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because of superior acid control, a fundamental component of GERD pathophysiology. However, despite the high rates with which PPIs heal esophagitis, it is now well recognized that a substantial proportion of individuals do not achieve complete or even adequate relief of symptoms. Alternative strategies to improve symptom control which interferes with a patient’s quality or life include high dose or twice-daily PPIs, newer delivery methods to improve pharmacologic effect over each dosing interval and the introduction of adjunctive treatments, including lifestyle modifications, to augment PPI activity. Pharmacologic targets other than acid control are being pursued but have not yet yielded marketable alternatives. Clinicians need to develop an awareness of the frequency with which patients on conventional PPI treatment are dissatisfied with treatment in order to consider strategies that may be effective for improving quality of life.

Epidemiology

Transient reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus is a normal and frequent physiologic event.(1)Although the majority of episodes are symptomless, periodic episodes of heartburn may occur in otherwise healthy individuals. The point at which episodes of heartburn meet the threshold of an empirical diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is based on frequency, chronicity, and the degree of the symptom burden. In Canada, consistent with other North American and European countries, approximately 17% of adults experience moderate to severe symptoms of GERD at least once weekly.(2)

There is growing evidence that NERD, GERD with esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus are related but independent phenotypes with distinct natural histories.

The symptoms of GERD have a significant adverse impact on quality of life whether or not they are associated with esophagitis,(3-4)which need not be present for a diagnosis of GERD.(5)Rather, while it was once thought that non-erosive GERD, often called NERD, was an early stage or milder form of GERD, there is growing evidence that NERD, GERD with esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus, characterized by metaplasia of the squamous epithelium, are related but independent phenotypes with distinct natural histories.(6)It is estimated that 50% to 85% of patients with GERD will not demonstrate esophagitis on endoscopy.(7)Of patients with NERD, only about 10% progress to esophagitis if followed long term.(5)The pathophysiology of functional heartburn, which is defined by heartburn in the absence of lesions or abnormalities in acid exposure on pH studies, is unknown and may incorporate several subgroups, including those with abnormalities of motility.(8)

Other evidence suggesting that NERD and erosive esophagitis are related but independent entities include differences in dominant risk factors. Although the list of risk factors overlap, elevated body weight and hiatal hernia are more closely associated with esophagitis, while psychological co-morbidities and extraesophageal symptoms are more commonly presented by patients with NERD.(9)In addition, NERD patients are less responsive to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.(9)In one study, the proportion of patients refractory to PPIs was more than three times greater in those with NERD relative to those with esophagitis (16.7% vs. 6%).(10)

In typical practice, treatment is offered without first differentiating NERD from esophagitis. According to Canadian guidelines, endoscopic investigation is not necessary unless patients present with alarm symptoms, which include involuntary weight loss, evidence of blood in the GI tract, or unexplained anemia, or if the goal is to rule out Barrett’s esophagus.(5)Endoscopy or other types of diagnostic studies, such as esophageal pH monitoring, may also be appropriate in patients with atypical symptoms, such as dysphagia, chest pain, or vomiting.

The rising rate of GERD over the past two decade (11)are not fully understood and may be due to multiple factors, including the growing rates of obesity, a risk factor for GERD.(12)While the increasing prevalence of GERD may be associated with increases in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma,(13)GERD by itself can be considered a serious disease for which the goal should be complete symptom control. While there is good data demonstrating that GERD is associated with substantial direct and indirect health costs,(14)uncontrolled or inadequately controlled symptoms not only have an adverse impact on numerous domains of quality of life, such as general perception of overall health status, they can interfere with diet, impair sleep, and reduce productivity.(15-16)

Pathophysiology of Acid

Although there is an association between symptoms and the degree and duration of refluxed acidic gastric contents,(17)there also appears to be substantial variability for the threshold at which symptoms are experienced, whether defined by pH or reflux duration.(18)When PPIs were introduced, they replaced H2-receptor antagonists because, acting on the final common pathway of gastric acid production in the parietal cell, they provided greater acid inhibition for a longer duration.(19)A direct relationship between acid control and both symptom control and healing of esophagitis is relevant to pharmacologic agents as well as surgical interventions used in the treatment of GERD.(20)

PPIs act by irreversibly binding to the proton pump in the parietal cell, thereby impeding the hydrogen-potassium exchange fundamental to acid secretion.(21)Due to the irreversibility, acid secretion is restored only when new pumps are formed, which occurs with meal stimulation.(22)As the serum half-life of PPIs is only two to three hours,(21)the window of time in which proton pump binding and inhibition takes place is relatively short. Although higher doses may bind a higher proportion of existing proton pumps, the incremental benefit is small.(23)Acid suppression persists because of the irreversible binding, there is a diminishing effect over time as new proton pumps are formed.(21)

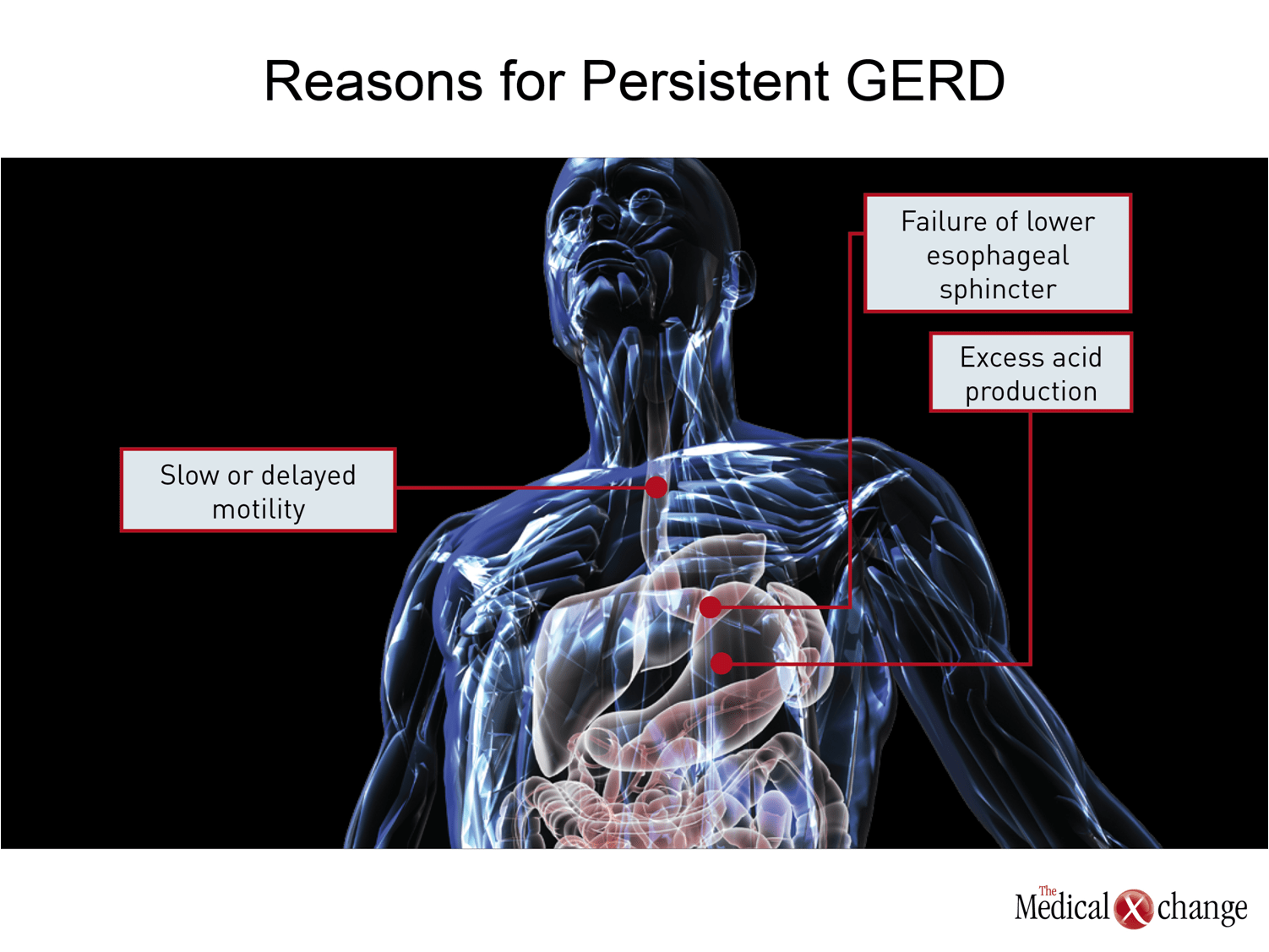

The goal of reducing gastric acid production with PPIs is to increase the pH of the refluxate into the esophagus to reduce risk of damage and acid-driven symptoms. Another approach is to improve the barrier to reflux from the stomach into the esophagus. This is the mechanism of benefit from fundoplication and the strategy behind numerous endoscopic procedures, most of which have not yet demonstrated convincing benefit over sustained periods.(24)Pharmacologic therapies to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which is the primary physiologic barrier to reflux, have been pursued.(25)These efforts, like alternative pharmacologic approaches to acid suppression, have not yet generated an effective and safe treatment (Fig. 1).

Unmet Needs in GERD Therapy

The need to improve therapy for GERD is driven by the substantial proportion of patients who do not achieve adequate symptom relief on conventional doses of PPIs.

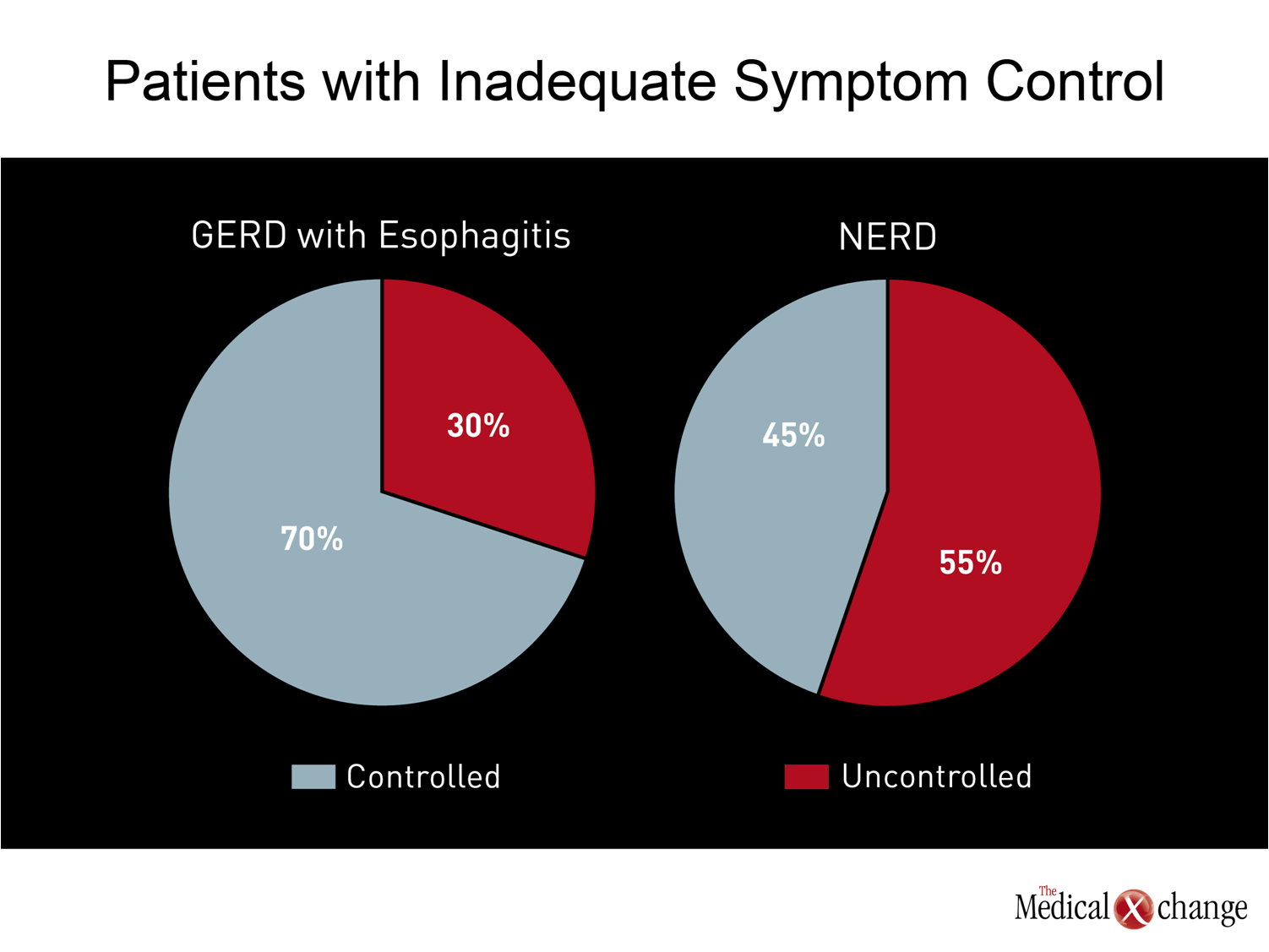

The need to improve therapy for GERD is driven by the substantial proportion of patients who do not achieve adequate symptom relief on conventional doses of PPIs. In patients with esophagitis on endoscopy, 20% to 30% continue to experience symptoms even if the esophagitis is healed.(26)In patients with NERD, less than 50% of patients achieve complete symptom resolution on a standard dose of PPI (Fig. 2).(7)Patients achieving complete resolution of nocturnal symptoms on standard doses of PPIs is worse in both groups.(27)In one survey conducted in the United States of patients taking a PPI, 80% reported that they had symptoms within the previous 30 days.(28)Of these, 22% were on twice-daily PPIs, and almost half supplement that PPI with another agent, such as an H2-receptor antagonist or an antacid.

Although a more rapid and complete symptomatic response is more common in patients with esophagitis, the presence or absence of inflammation is not typically known to the treating physician. However, the goal should include symptom relief whether or not patients have esophagitis. Persistent symptoms produce a reduction in quality of life on the order of that experienced by patients who have survived a coronary event.(29)In those with symptoms described by patients as disrupting, GERD is associated with significant increases in absenteeism, reduced work productivity, and higher consumption of healthcare services.(30)

In patients who undergo endoscopy and receive a diagnosis of esophagitis, healing is an important goal. The risk of untreated GERD includes Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma.(31)Patients who undergo endoscopy may be reassured by the absence of lesions, but symptoms of GERD should not be considered benign when they interfere with functions of daily life. The efficacy of PPIs relative to previous options for the treatment of GERD may have initially diverted attention from the substantial proportion of patients who do not obtain adequate relief from these agents, but this unmet need has now generated increasing attention in clinical research. More attention is also needed for understanding the causes and the potential treatments for functional heartburn. PPIs are not typically effective in patients with this diagnosis,(8)which may incorporate an array of disorders including those stemming from problems of motility or the consequences of psychogenic mood disorders.

Next Steps in GERD Therapy

In addressing inadequate relief of GERD symptoms in patients who are being treated with a PPI, it is important to consider adherence to therapy and alternative sources of pain or discomfort, not the least of which includes angina. However, in an otherwise healthy and adherent patient, the problem may simply be one of inadequate acid control. One explanation for persistent symptoms in some but not all individuals with GERD who receive a conventional dose of PPI is the variability in sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa to acid contact. Although symptoms do correlate with the extent of acid exposure in patients with NERD, as in those with esophagitis, the threshold of sensitivity differs.(32)This is the reason that the focus on improving symptom control has remained largely on improving acid control.

Unlike higher doses of PPIs, which provides limited additional benefit for control of acid,(33)twice-daily regimens address the formation of new proton pumps and have been shown to improve symptom control, including nocturnal symptoms.(34)However, twice-daily regimens increase the burden on patient compliance, particularly as timing of medication relative to meal-stimulated formation of pumps is important.

An alternative that is conceptually appealing is to extend the activity time of a once-daily PPI by prolonging its antisecretory effect.

An alternative that is conceptually appealing is to extend the activity time of a once-daily PPI by prolonging its antisecretory effect. Several PPIs with unique pharmacokinetics have been evaluated in clinical testing, including dexlansoprazole, which is now licensed in Canada. Dexlansoprazole, a PPI that is structurally related to, but more potent than, lansoprazole (35)has been formulated in a capsule that employs a mixture of two types of enteric coated granules, allowing it to provide two distinct peak concentrations.(36)One occurs, like other PPIs, one or two hours after administration, and the second peak at three to four hours later, permitting this agent to extend its activity over a longer period when acid pumps are being formed.

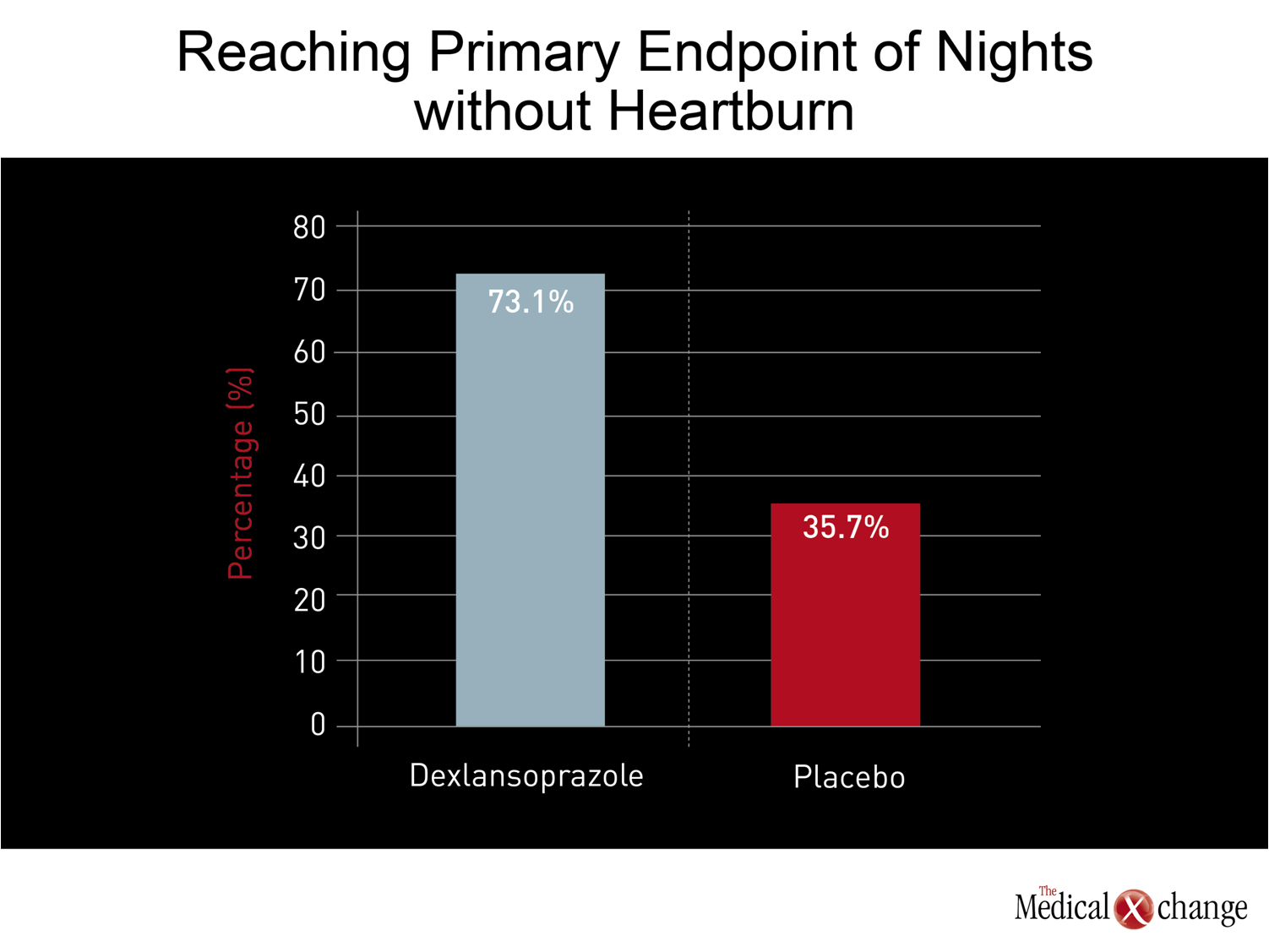

While the licensing of dexlansoprazole was based on conventional double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that associated this agent with both safety and efficacy,(37)more recent studies have focused on the role on this agent for indications where other PPIs have been less effective, particularly nocturnal GERD. In the most recent study, 305 patients with nocturnal heartburn were randomized to 30 mg dexlansoprazole or placebo.(38)Dexlansoprazole was not only highly effective for the primary endpoint of nights without heartburn (73.1% vs. 35.7%; P<0.001) (Fig. 3) but was associated with significant improvements in sleep quality and work productivity.

Similar approaches to improving the pharmacokinetics of PPI delivery have been attempted with tentaprazole and a prodrug of omeprazole.(39-40)These studies have reinforced the feasibility of this approach, which is encouraging because of the limited alternatives. Although other pharmacologic approaches once seemed promising, such as potassium-competitive acid blockers, and agents that inhibit transient lower esophageal relaxations, much of the work in these areas has been stopped because of unanticipated side effects. While both concepts are based on the goal of reducing the amount of acid that reaches the lower esophagus, the effort to improve the pharmacokinetics of PPIs appears to provide the best current pharmacologic option for improving GERD therapy.

Conclusion

The efficacy of PPIs in the treatment of GERD, as well as other acid-related gastrointestinal disorders, relative to previous options may have delayed the attention now being paid to those who are not achieving adequate symptom relief on conventional doses of these agents. While PPIs do provide very high rates of esophagitis healing, approximately 30% of patients with inflammation and an even higher proportion without esophagitis remain symptomatic. The inadequacy of control is greatest for nocturnal symptoms. Although more frequent dosing may be a solution for some proportion of individuals, modified pharmacokinetics to lengthen the availability of drug available for proton pump binding is another. Efforts to identify patients with persistent symptoms to offer alternative treatment approaches can be expected to be rewarded with substantial improvements in quality of life and wellbeing.

References

1. Orlando RC. The pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the relationship between epithelial defense, dysmotility, and acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92(4 Suppl):3S-5S; discussion S-7S.

2. Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Eggleston A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94(10):2845-54.

3. Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med 1998;104(3):252-8.

4. El-Dika S, Guyatt GH, Armstrong D, et al. The impact of illness in patients with moderate to severe gastro-esophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2005;5:23.

5. Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, et al. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults – update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19(1):15-35.

6. Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and erosive esophagitis–a spectrum of disease or special entities? Z Gastroenterol 2007;45(11):1156-63.

7. El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion 2008;78 Suppl 1:6-10.

8. Fass R, Tougas G. Functional heartburn: the stimulus, the pain, and the brain. Gut 2002;51(6):885-92.

9. Dean BB, Gano AD, Jr., Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2(8):656-64.

10. Lee ES, Kim N, Lee SH, et al. Comparison of risk factors and clinical responses to proton pump inhibitors in patients with erosive oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30(2):154-64.

11. El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5(1):17-26.

12. Sonnenberg A. Effects of environment and lifestyle on gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis 2011;29(2):229-34.

13. Ryan AM, Duong M, Healy L, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and esophageal adenocarcinoma: Epidemiology, etiology and new targets. Cancer Epidemiol 2011.

14. Fedorak RN, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Bridges R. Canadian Digestive Health Foundation Public Impact Series: gastroesophageal reflux disease in Canada: incidence, prevalence, and direct and indirect economic impact. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24(7):431-4.

15. Gisbert JP, Cooper A, Karagiannis D, et al. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on patients’ daily lives: a European observational study in the primary care setting. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:60.

16. Liker HR, Ducrotte P, Malfertheiner P. Unmet medical needs among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a foundation for improving management in primary care. Dig Dis 2009;27(1):62-7.

17. Wang C, Hunt RH. Precise role of acid in non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion 2008;78 Suppl 1:31-41.

18. Smith JL, Opekun AR, Larkai E, Graham DY. Sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa to pH in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1989;96(3):683-9.

19. Katz PO, Johnson DA. Control of Intragastric pH and Its Relationship to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011.

20. Bell NJ, Burget D, Howden CW, Wilkinson J, Hunt RH. Appropriate acid suppression for the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion 1992;51 Suppl 1:59-67.

21. Sachs G, Shin JM, Howden CW. Review article: the clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23 Suppl 2:2-8.

22. Savarino V, Di Mario F, Scarpignato C. Proton pump inhibitors in GORD An overview of their pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Pharmacol Res 2009;59(3):135-53.

23. Orlando RC, Liu S, Illueca M. Relationship between esomeprazole dose and timing to heartburn resolution in selected patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2010;3:117-25.

24. Chen D, Barber C, McLoughlin P, Thavaneswaran P, Jamieson GG, Maddern GJ. Systematic review of endoscopic treatments for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg 2009;96(2):128-36.

25. Boeckxstaens GE, Beaumont H, Mertens V, et al. Effects of lesogaberan on reflux and lower esophageal sphincter function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2010;139(2):409-17.

26. Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Evolving issues in the management of reflux disease? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2009;25(4):342-51.

27. Tytgat GN. Are there unmet needs in acid suppression? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004;18 Suppl:67-72.

28. Chey WD, Mody RR, Izat E. Patient and physician satisfaction with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): are there opportunities for improvement? Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(12):3415-22.

29. Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, et al. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease– an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18(8):767-76.

30. Toghanian S, Wahlqvist P, Johnson DA, Bolge SC, Liljas B. The burden of disrupting gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a database study in US and European cohorts. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30(3):167-78.

31. Gilbert EW, Luna RA, Harrison VL, Hunter JG. Barrett’s esophagus: a review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15(5):708-18.

32. Chua YC, Aziz Q. Perception of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24(6):883-91.

33. Gursoy O, Memis D, Sut N. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on gastric juice volume, gastric pH and gastric intramucosal pH in critically ill patients : a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig 2008;28(12):777-82.

34. Katz PO, Hatlebakk JG, Castell DO. Gastric acidity and acid breakthrough with twice-daily omeprazole or lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14(6):709-14.

35. Hershcovici T, Jha LK, Fass R. Dexlansoprazole MR – A review. Ann Med 2011;43(5):366-74.

36. Emerson CR, Marzella N. Dexlansoprazole: A proton pump inhibitor with a dual delayed-release system. Clin Ther 2010;32(9):1578-96.

37. Sharma P, Shaheen NJ, Perez MC, et al. Clinical trials: healing of erosive oesophagitis with dexlansoprazole MR, a proton pump inhibitor with a novel dual delayed-release formulation–results from two randomized controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29(7):731-41.

38. Fass R, Johnson DA, Orr WC, et al. The effect of dexlansoprazole MR on nocturnal heartburn and GERD-related sleep disturbances in patients with symptomatic GERD. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(3):421-31.

39. Hunt RH, Armstrong D, Yaghoobi M, et al. Predictable prolonged suppression of gastric acidity with a novel proton pump inhibitor, AGN 201904-Z. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28(2):187-99.

40. Hunt RH, Armstrong D, Yaghoobi M, James C. The pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of S-tenatoprazole-Na 30 mg, 60 mg and 90 mg vs. esomeprazole 40 mg in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31(6):648-57.

Chapter 3: GERD – The Era of PPIs

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) replaced previous options for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because of superior acid control, a fundamental component of GERD pathophysiology. However, despite the high rates with which PPIs heal esophagitis, it is now well recognized that a substantial proportion of individuals do not achieve complete or even adequate relief of symptoms. Alternative strategies to improve symptom control which interferes with a patient’s quality or life include high dose or twice-daily PPIs, newer delivery methods to improve pharmacologic effect over each dosing interval and the introduction of adjunctive treatments, including lifestyle modifications, to augment PPI activity. Pharmacologic targets other than acid control are being pursued but have not yet yielded marketable alternatives. Clinicians need to develop an awareness of the frequency with which patients on conventional PPI treatment are dissatisfied with treatment in order to consider strategies that may be effective for improving quality of life.

Show review