Expert Review

Unmet Needs in PPI Therapy for GERD

Chapter 1: GERD – Current Challenges in Control

David Armstrong, MA, MB BChir, FRCP(UK), FACG, AGAF, FRCPC

McMaster University, Hamilton, ON

The reasons that patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) fail to achieve adequate symptom relief with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have proven surprisingly complex. While high rates of healing are achieved in patients with erosive esophagitis on conventional once-daily doses of PPIs, the proportion of patients with persistent symptoms despite healing is substantial. Relative to those with esophagitis, the proportion of patients with inadequate symptom control is even higher in patients with endoscopy-negative GERD (NERD). The large body of research exploring the relationship of acid- and non-acid reflux to symptoms of GERD has expanded the understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms. Insights from this research are guiding strategies with the potential to address deficiencies of current therapies. In essence, GERD has proven to be a heterogeneous entity with contributing etiological factors not limited to excess gastric acid secretion. A systematic approach toward understanding the key mechanisms of symptom genesis may improve treatment success.

Definition and Epidemiology

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a product of the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. As most individuals have occasional episodes of reflux, the threshold at which these episodes become pathologic is when the associated symptoms are troublesome.(1)This patient-centered definition recognizes that GERD is a symptom-based disease even if complications can include erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and extra-esophageal symptoms such as laryngitis and chronic cough. By definition, GERD requires retrograde movement of gastric contents but it does not exclude the co-existence of other conditions affecting the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract; furthermore, reflux may be associated with symptoms other than those considered typical of GERD. In a Canadian study of dyspepsia that excluded patients whose symptom description was limited to complaints of heartburn or regurgitation, 54.7% were found to have esophagitis when endoscopy was performed.(2)Even though a large proportion of these patients reported heartburn or regurgitation within their constellation of symptoms, this study reinforces the notion that GERD is common in uninvestigated dyspepsia patients who have symptoms that are not limited to heartburn. When extrapolated to Canada, incidence rates of approximately 5 per 1000 patient years in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK), predict about 170,000 new diagnoses of GERD per year.(3)Although a recent review of population-based studies was unable to corroborate a previous assertion that the incidence of GERD increases with age, it did suggest that older patients are more likely to develop erosive esophagitis.(4)That analysis also concluded that GERD symptoms become less severe and less characteristic with age. Due to the heterogeneity of GERD symptom expression, these findings are potentially relevant to clinicians delivering care in countries, like Canada, with a growing proportion of the population older than age 60 years. Despite recent attention to the role of non-acid or weakly acidic reflux as a source of GERD symptoms,(5)acid control remains the fundamental principle of therapy. Response to acid control is so characteristic of GERD, that a trial of antisecretory therapy, particularly a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), has been defined by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) as a positive diagnostic test.(6)However, failure to respond to a PPI, particularly if prescribed once daily, does not rule out GERD. Although lack of response should prompt efforts to identify an alternative cause of symptoms, a diagnosis of refractory GERD can be considered if twice-daily PPI therapy does not adequately relieve symptoms and if no alternative etiology can be identified.(3)

There is a substantial proportion of patients with GERD who fail conventional, once-daily PPI therapy when symptom control is the endpoint.

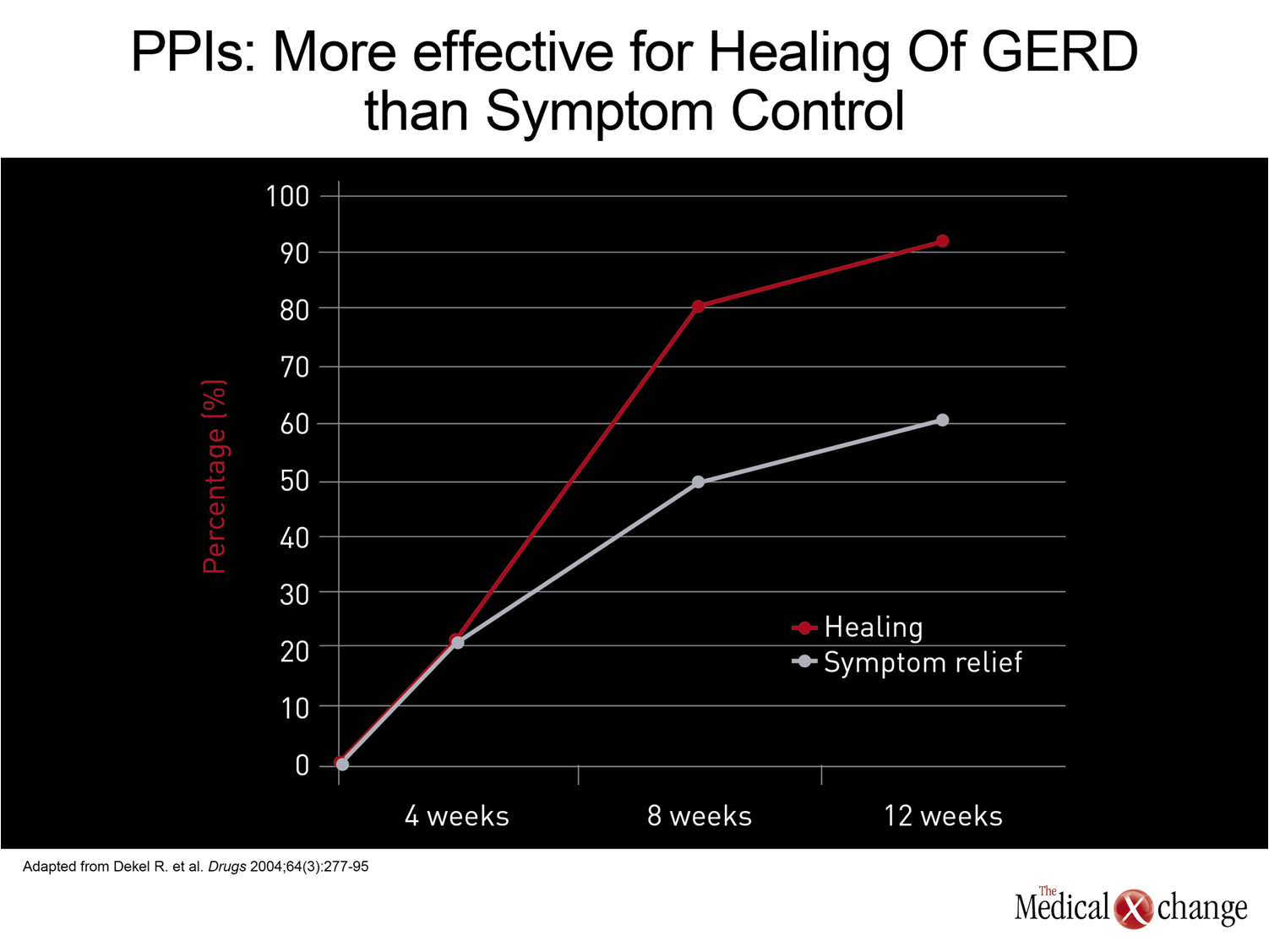

There is a substantial proportion of patients with GERD who fail conventional, once-daily PPI therapy when symptom control is the endpoint. In contrast to healing rates, which have typically exceeded 90% in outcome trials of 8 to 12 weeks, rates of symptom control have been in the order of 50% to 65%.(7)In patients with non-erosive esophageal reflux disease (NERD), rates of symptom control are generally reported to be lower than those achieved in patients with esophagitis.(8)However, most treatment trials in patients with NERD have been limited to 4 weeks and there are data, at least in uninvestigated patients with heartburn, to show that the proportion of patients with symptom relief increases with continued therapy, up to 12 weeks.(9)Although the rates of symptom control have been far greater with PPIs than with any other therapy used in the treatment of GERD, the need for better treatments is driven by the important relationship between symptoms and diminished quality of life.(10) (Fig. 1)

GERD versus NERD

Although it is possible that NERD is best characterized as an early stage or mild form of GERD, it has been proposed that NERD is a distinct entity that has a modest risk of progression to esophagitis and complications.

The CAG guidelines endorse empirical treatment of heartburn and regurgitation in the absence of alarm symptoms, such as unexplained weight loss or signs of bleeding, on the presumption of underlying GERD.(6)In responders, no further investigations may ever be conducted, precluding subclassification of GERD into its erosive esophagitis and NERD subtypes. Although it is possible that NERD is best characterized as an early stage or mild form of GERD, it has been proposed that NERD is a distinct entity that has a modest risk of progression to esophagitis and complications.(11)However, our understanding of NERD is hampered by the fact that there is no objective test to confirm reflux – acid or non-acid – in NERD patients since, by definition, they have no endoscopic evidence of injury. In the absence of reflux, antireflux therapy would not be expected to be effective. If, however, the symptoms are caused by reflux of gastric constituents other than acid, which are perhaps less likely to cause erosive esophagitis, gastric acid control may also be ineffective. Although antisecretory therapies are effective in the majority of NERD patients, only about half of patients with NERD have acid levels in the lower esophagus that are above the physiological range.(12)Overall, the pathophysiology and natural history of NERD remain unclear.

The complex relationship between acid control and symptom relief may be valuable to efforts to improve successful empirical management of GERD.

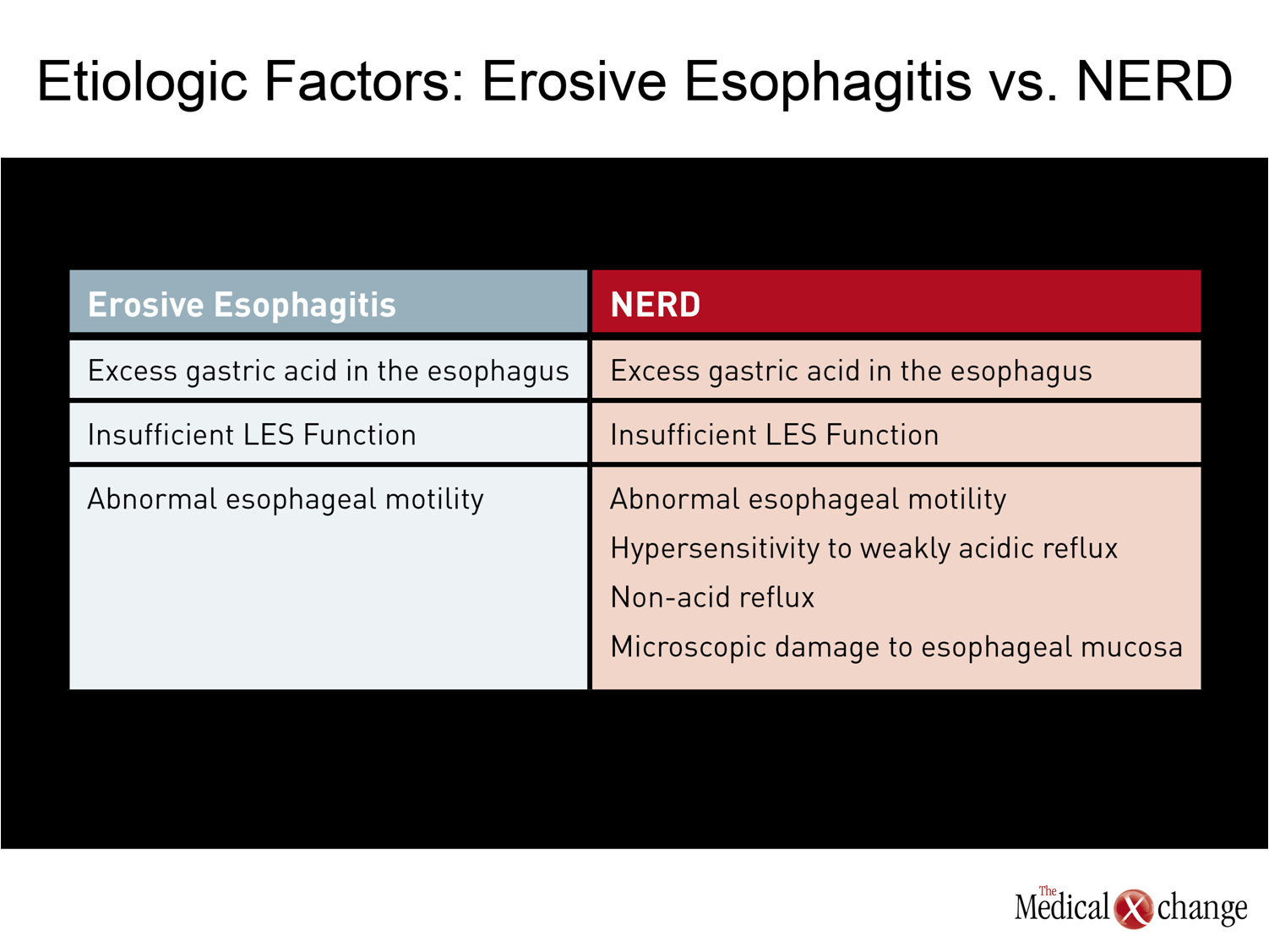

Unlike esophagitis, where the straightforward relationship between excess acid and inflammation is apparent in the high rates of healing achieved by raising lower esophageal pH, the more complex relationship between acid control and symptom relief may be valuable to efforts to improve successful empirical management of GERD. Of several plausible explanations for NERD in the absence of elevated acid levels, visceral hypersensitivity is among the strongest.(13)There are several mechanisms by which nociceptive receptors in the esophageal mucosa in patients with NERD may generate the pain signals that underlie symptoms. In addition to hypersensitivity to weakly acidic reflux,(14)these include microscopic impairments in mucosal integrity that may increase access of acid or other gastric constituents to nerves, producing symptoms at levels of pH not normally considered pathologic.(15) (Table 1) Not all symptoms may be acid related in patients with symptoms consistent with GERD. For example, patients with a sensitive esophagus may complain of GERD symptoms when they drink citrus juices or alcohol or eat tomatoes or spicy foods. These exposures do not necessarily exacerbate GERD or reflux. Rather, they may simply irritate an esophagus that is already sensitive or injured. In addition, changes in motility due to impaired peristaltic function can cause upper GI symptoms. Although motility disorders are a far less common source of upper GI symptoms than acid-driven heartburn, this source of symptoms is now more easily detected with the introduction of high-resolution manometry.(16)For non-acid-related symptoms, pH monitoring, impedance monitoring, and manometry are useful for identifying the underlying causes of symptoms in non-responders to PPI therapy, but these tools are generally reserved for patients whose symptoms persist after several trials of pharmacologic therapy, particularly higher or more frequent doses of PPIs.

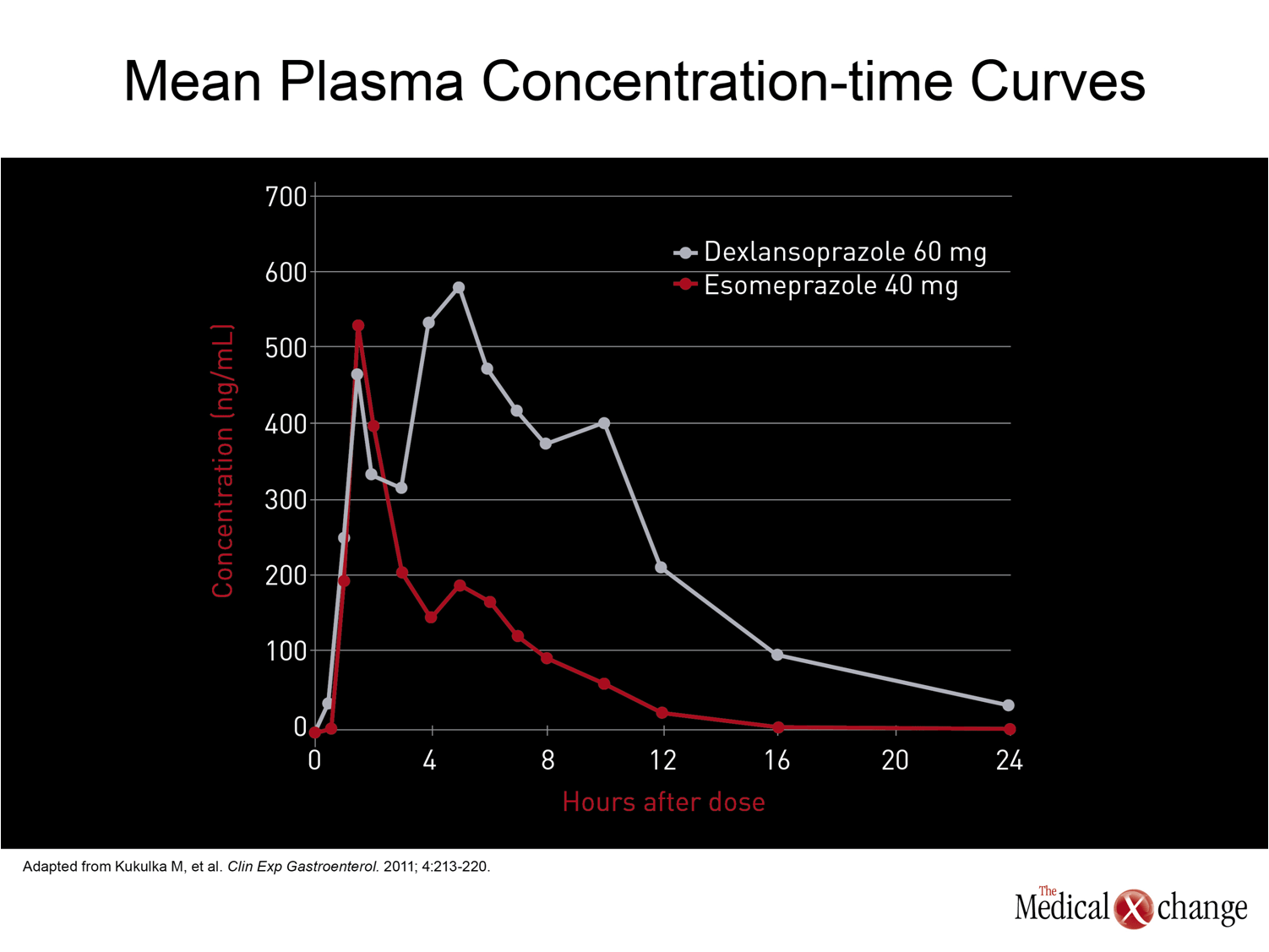

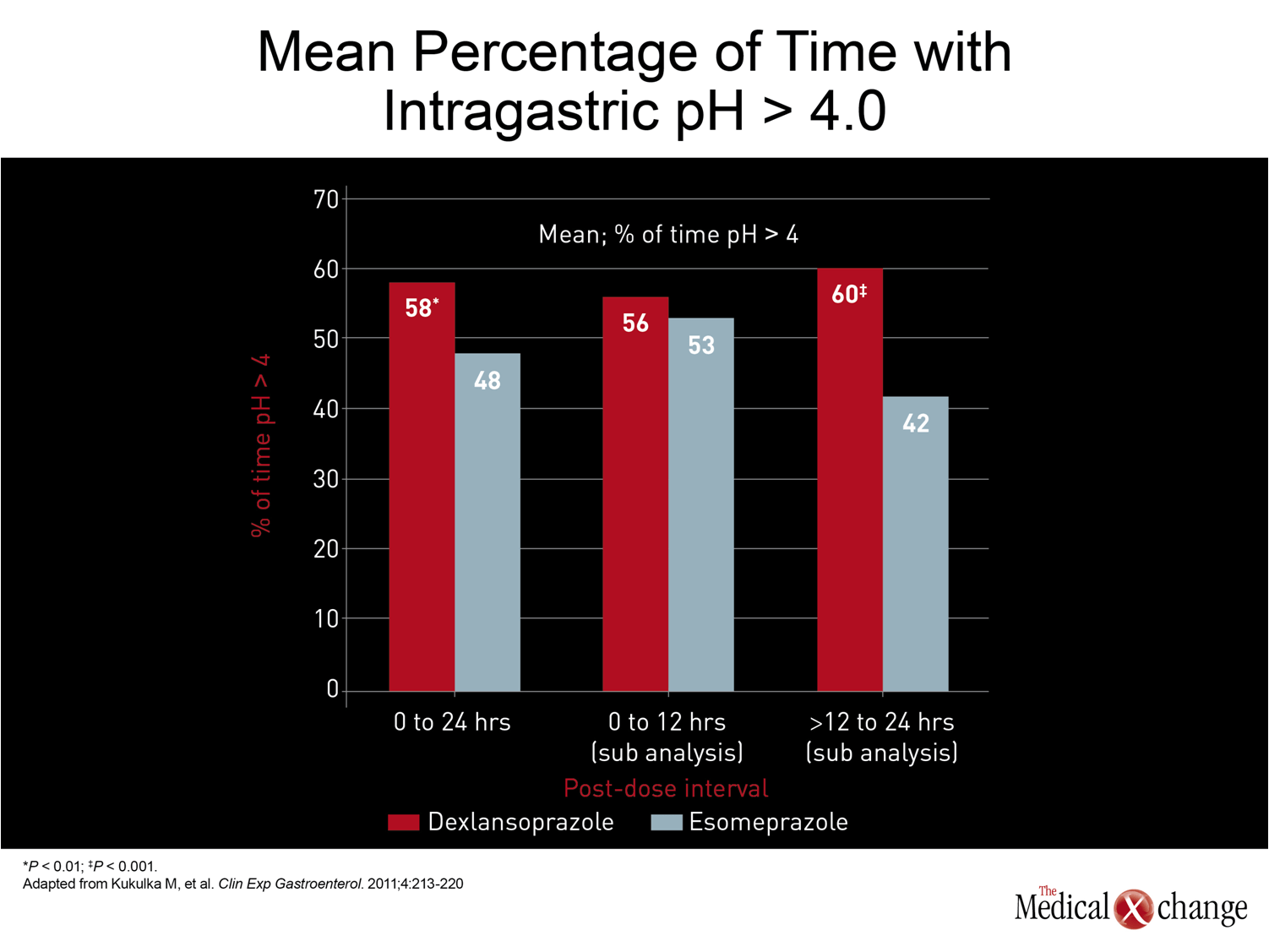

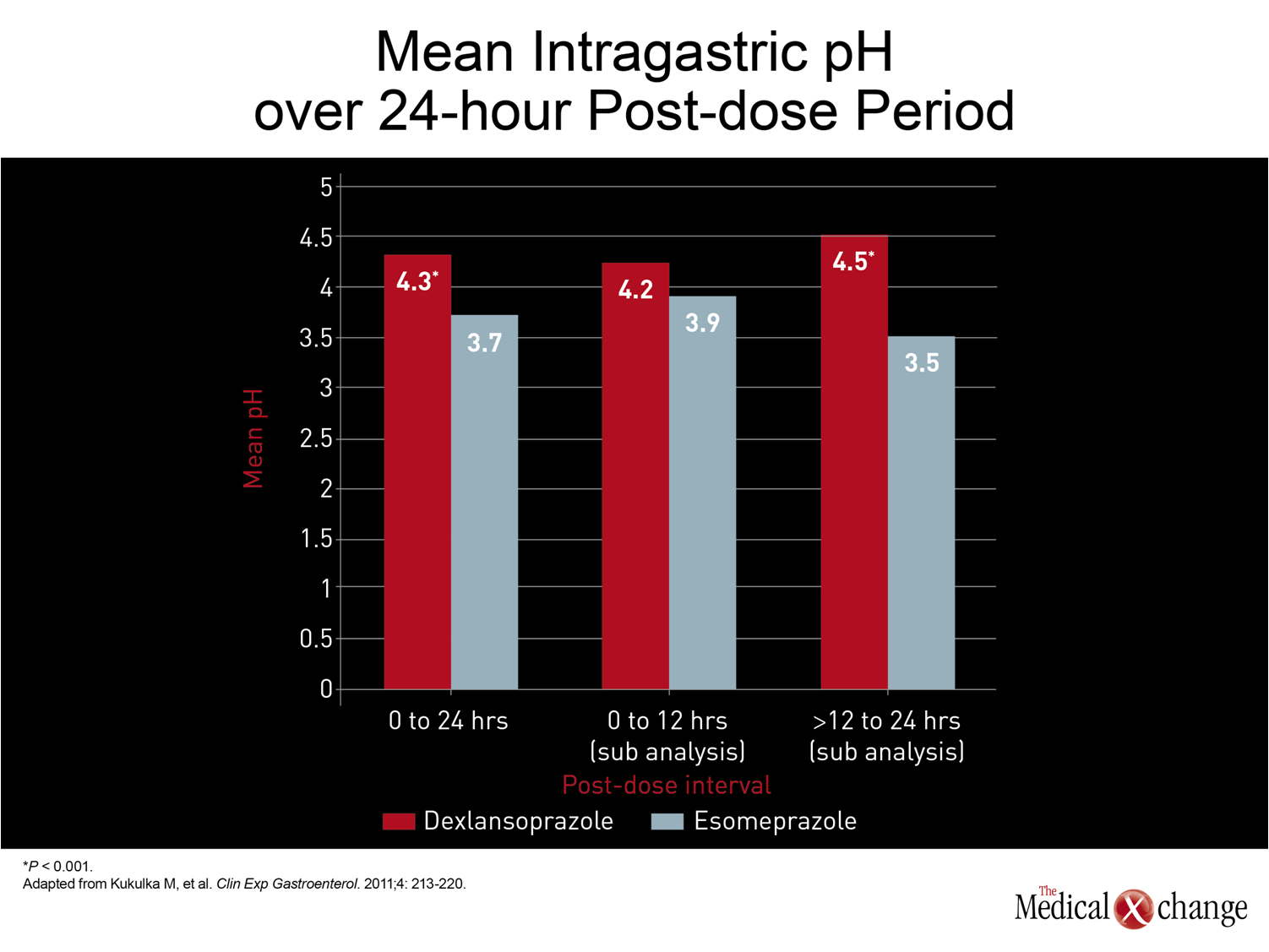

Treatment: Improving Response with Acid Control

The CAG guidelines recommend once-daily PPI therapy in a standard dose for symptoms of persistent GERD.(6)The standard dose of the first drug in this class, omeprazole, is 20 mg. The standard doses of subsequently marketed PPIs, which differ modestly in metabolism and pharmacokinetics, have ranged from 20 mg to 40 mg. In general, the efficacy differences, if any, between the first generation PPIs did not appear to be substantial. Although there were no large scale head-to-head comparisons with clinical endpoints until the introduction of esomeprazole, the S-enantiomer of the parent compound omeprazole, healing rates of esophagitis and symptom control in uninvestigated GERD were of the same order of magnitude. In trials with esomeprazole, which increased the proportion of each 24-hour dosing period with pH >4.0,(17)healing rates have been superior relative to the previously available PPIs, which, in addition to omeprazole, included lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole.(18) The advantage of greater acid control for GERD management, demonstrated with the relative advantage of esomeprazole over previous PPIs, has fostered other strategies to more effectively suppress acid over each dosing period to improve clinical benefit. These strategies have included doubling the dose of PPIs, typically by twice-daily administration,(19)or adding a histamine H2-receptor antagonist.(20)One of the potential disadvantages of these strategies is that they forsake the compliance advantage inherent in a once-daily therapy. More recently, an alternative strategy has been introduced with a new PPI, dexlansoprazole, that employs a dual-delayed release delivery technology which produces two plasma peaks.(21)In a randomized study, evaluating intragastric pH, dexlansoprazole produced an improvement over the standard dose of esomeprazole that esomeprazole had produced over previous PPIs (Fig. 2).(22)While the mean pH over 24 hours was superior for dexlansoprazole (4.3 vs. 3.7; P4.0 (60% vs. 42%; P<0.001) and average mean pH (4.5 vs. 3.5; P<0.001) predict better control of the acid-driven symptoms of GERD (Fig. 3) and (Fig. 4). For empirical therapy of GERD, there is a reasonable expectation that the greatest likelihood of symptom control will be achieved with greater acid control over each dosing period. Improved acid suppression during the nighttime hours is particularly important, because up to 80% of patients with GERD report nighttime symptoms and, nearly half of those report impaired quality of sleep.(23)Based on the modest therapeutic gain from increasing the dose of once-daily PPIs, the patterns of inadequate symptom relief from traditional PPIs suggest that the deficiency occurs because acid suppression is not was not sustained adequately. This is consistent with the formation of new acid pumps after serum levels of PPIs are no longer high enough to irreversibly block pump function; the re-emergence of actively-secreting proton pumps during the latter part of the 24-hour dosing period is susceptible to treatment by longer-acting PPIs that can sustain high levels for longer periods. So far, other pharmacologic strategies, such as drugs designed to improve tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), have not yet proven to be clinically viable but may prevail in ongoing clinical studies.(24)While surgery to improve LES function remains a therapeutic option for GERD, benefits are not necessarily superior to PPI for acid-driven symptoms.(25)This makes strategies for delivering active drugs over a longer period of acid pump formation one of the most attractive methods for improving symptom control.

Conclusion

In patients presenting with GERD, in the absence of alarm symptoms, empiric treatment with PPIs serves as both a diagnostic study and a treatment. For esophagitis, PPIs have a very high rate of success, healing most patients in standard doses. While there is no pharmacologic therapy superior to PPIs for control of symptoms, the limitation of standard doses of PPIs has been a growing concern because of the strong relationship between persistent symptoms and diminished quality of life. While acid may not always be the critical factor in patients with inadequately controlled GERD-like symptoms, incremental improvements in acid control with more effective PPIs or more effective delivery of PPIs promise greater efficacy and should be considered before pursuing additional diagnostic studies to rule out non-acid sources of symptomatology.

References

1. Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(8):1900-20; quiz 43. 2. Thomson AB, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, et al. The prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment – Prompt Endoscopy (CADET-PE) study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17(12):1481-91. 3. Fedorak RN, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Bridges R. Canadian Digestive Health Foundation Public Impact Series: gastroesophageal reflux disease in Canada: incidence, prevalence, and direct and indirect economic impact. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24(7):431-4. 4. Becher A, Dent J. Systematic review: ageing and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms, oesophageal function and reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33(4):442-54. 5. Karamanolis G, Kotsalidis G, Triantafyllou K, et al. Yield of combined impedance-pH monitoring for refractory reflux symptoms in clinical practice. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;17(2):158-63. 6. Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, et al. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults – update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19(1):15-35. 7. Dekel R, Morse C, Fass R. The role of proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Drugs2004;64(3):277-95. 8. van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Lau J, de Wit NJ, Hungin AP, Bonis PA. Short-term treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease.J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(9):755-63. 9. Armstrong D, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Barkun AN, et al. Heartburn-dominant, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a comparison of ‘PPI-start’ and ‘H2-RA-start’ management strategies in primary care–the CADET-HR Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21(10):1189-202. 10. Becher A, El-Serag H. Systematic review: the association between symptomatic response to proton pump inhibitors and health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34(6):618-27. 11. Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and erosive esophagitis–a spectrum of disease or special entities? Z Gastroenterol 2007;45(11):1156-63. 12. Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)–acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17(4):537-45. 13. Knowles CH, Aziz Q. Visceral hypersensitivity in non-erosive reflux disease. Gut 2008;57(5):674-83. 14. Miwa H, Kondo T, Oshima T, Fukui H, Tomita T, Watari J. Esophageal sensation and esophageal hypersensitivity – overview from bench to bedside. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;16(4):353-62. 15. Farre R, Fornari F, Blondeau K, et al. Acid and weakly acidic solutions impair mucosal integrity of distal exposed and proximal non-exposed human oesophagus. Gut 2010;59(2):164-9. 16. Roman S, Zerbib F, Belhocine K, des Varannes SB, Mion F. High resolution manometry to detect transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations: diagnostic accuracy compared with perfused-sleeve manometry, and the definition of new detection criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34(3):384-93. 17. Miner P, Jr., Katz PO, Chen Y, Sostek M. Gastric acid control with esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole: a five-way crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(12):2616-20. 18. Gralnek IM, Dulai GS, Fennerty MB, Spiegel BM. Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4(12):1452-8. 19. Fass R. Proton pump inhibitor failure–what are the therapeutic options? Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104 Suppl 2:S33-8. 20. Mainie I, Tutuian R, Castell DO. Addition of a H2 receptor antagonist to PPI improves acid control and decreases nocturnal acid breakthrough.J Clin Gastroenterol 2008;42(6):676-9. 21. Vakily M, Zhang W, Wu J, Atkinson SN, Mulford D. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a known active PPI with a novel Dual Delayed Release technology, dexlansoprazole MR: a combined analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25(3):627-38. 22. Kukulka M, Eisenberg C, Nudurupati S. Comparator pH study to evaluate the single-dose pharmacodynammics of dualy delayed-released dexlansoprazole 60 mg and delayed-release esomeprazole 40 mg. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology 2011;4:213-20. 23. Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, et al. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(1):45-52. 24. Blondeau K. Treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: the new kids to block. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22(8):836-40. 25. Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011;305(19):1969-77. 26. Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): 3-year outcomes. Surg Endosc 2011;25(8):2547-54.

Chapter 1: GERD – Current Challenges in Control

The reasons that patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) fail to achieve adequate symptom relief with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have proven surprisingly complex. While high rates of healing are achieved in patients with erosive esophagitis on conventional once-daily doses of PPIs, the proportion of patients with persistent symptoms despite healing is substantial. Relative to those with esophagitis, the proportion of patients with inadequate symptom control is even higher in patients with endoscopy-negative GERD (NERD). The large body of research exploring the relationship of acid- and non-acid reflux to symptoms of GERD has expanded the understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms. Insights from this research are guiding strategies with the potential to address deficiencies of current therapies. In essence, GERD has proven to be a heterogeneous entity with contributing etiological factors not limited to excess gastric acid secretion. A systematic approach toward understanding the key mechanisms of symptom genesis may improve treatment success.

Show review