Expert Review

Severe Asthma: Characterization for Individualized Therapy

Chapter 4: Anti-IL-5 Therapy and Other Biologics in Severe Asthma

J. Mark FitzGerald, MD, FRCPC

Professor, Division of Respirology, University of British Columbia,

Vancouver, British Columbia

Monoclonal antibodies targeted at the interleukin-5 (IL-5) pathway have been associated with benefit in severe eosinophilic asthma suboptimally responsive to optimized inhaled therapy, such as corticosteroids plus a long-acting beta agonist. The inhibition of IL-5 has helped establish eosinophils, which mature and proliferate in response to the IL-5 cytokine, as a targetable mediator of airway inflammation. An evaluation of the rationale, design, and outcomes of the clinical trials with IL-5 inhibitors informs current indications, but their role may evolve on the basis of studies designed to address unanswered questions, such as the relative importance of eosinophil depletion. Differences in anti-IL-5 therapies, including their mechanism, may be clinically relevant and contribute to a more thorough understanding of how these therapies control airway inflammation. Although biologics have been relatively well tolerated even when administered over extended periods, patient selection and individualized care are essential to their application in cost-effective treatment.

Background

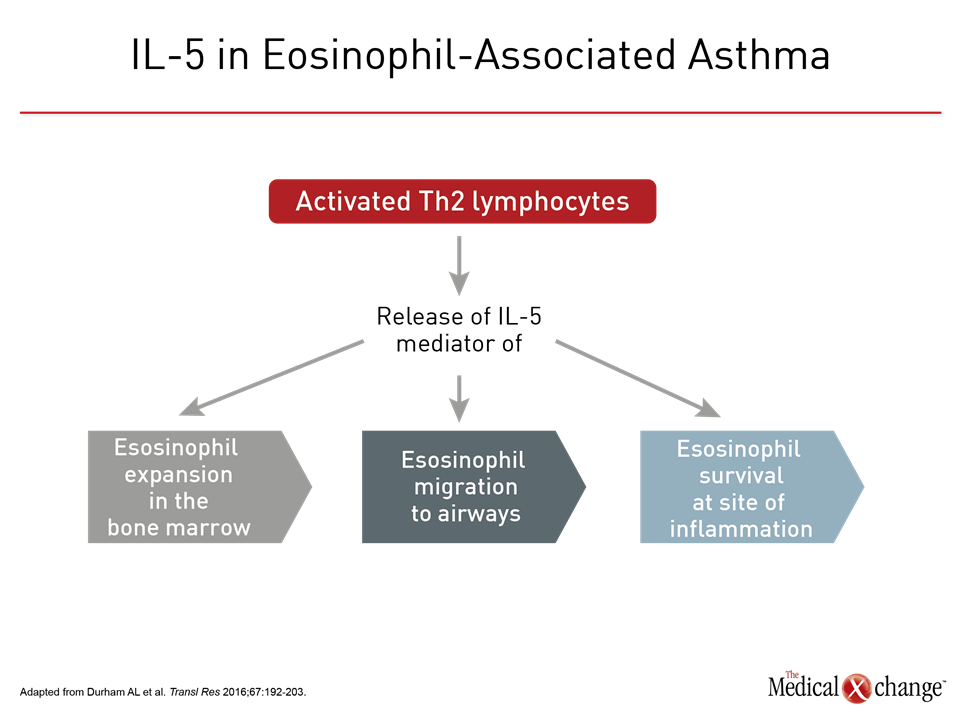

The association between eosinophilia and asthma has been recognized for more than a century.1 The potential for eosinophilia to be a modifiable factor in asthma pathogenesis is suggested by the correlation between greater asthma severity and greater numbers of eosinophils in the blood and sputum.1 Even in advance of therapies designed to specifically downregulate or inhibit activation of eosinophils, reductions in sputum eosinophils achieved by adjusting inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) were associated with a reduction in asthma exacerbations.2,3 Eosinophils, like other leukocytes, are formed in the bone marrow, emerging fully differentiated into the bloodstream.4 They typically populate peripheral mucosal tissues, including lymphoid tissue, during their relatively short half-life. Although eosinophils have a number of progenitors in the bone marrow, the IL-5 cytokine has a central role in inducing eosinophil expansion.4 Other type 2 helper (Th2) T cell cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, participate in proliferation and migration in an inflammatory response, but IL-5, is implicated in all stages of eosinophil development, including expansion in the bone marrow, migration, and survival at the site of inflammation. IL-5 is widely considered the most important driver of eosinophil activity5 (Fig. 1).

Anti-IL-5 Phase 3 Trials

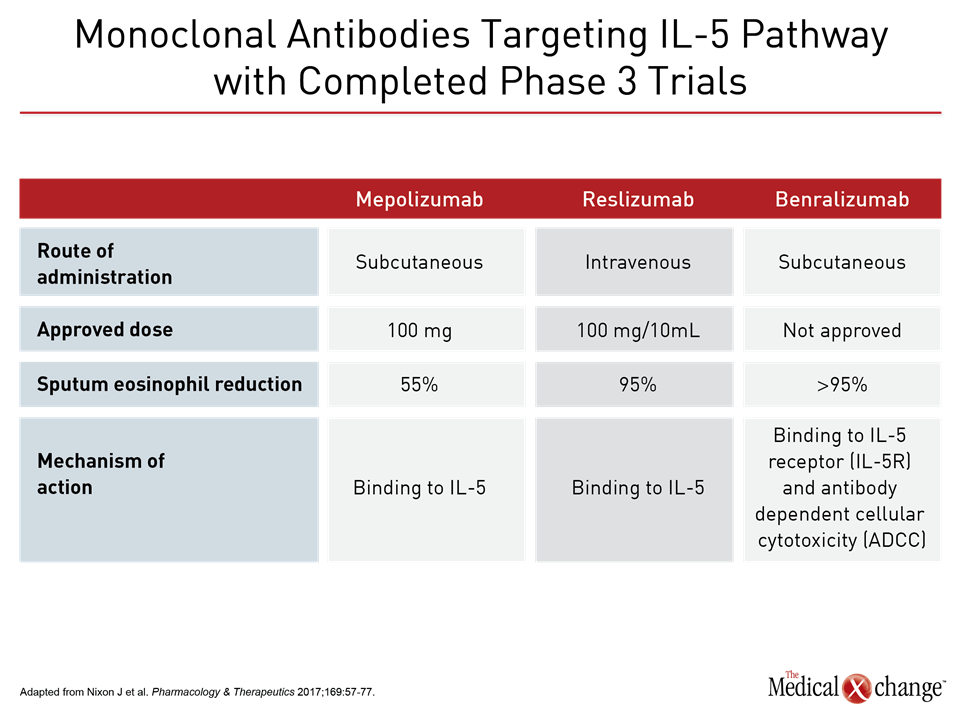

Three anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been evaluated for severe asthma in phase 3 trials. Two of these agents, mepolizumab and reslizumab, have received regulatory approval in Canada. Both bind to IL-5 to prevent its activity. A third agent, benralizumab was recently approved by the U.S. FDA and appears to be on track for regulatory approval in Canada based on completed studies. Unlike mepolizumab and reslizumab, benralizumab binds to the IL-5 receptor alpha (IL5Rα). Mepolizumab and benralizumab have been developed for subcutaneous (SQ) administration. Reslizumab is available for delivery by the intravenous (IV) route. As a result of the phase 3 trials, the labeling of mepolizumab and reslizumab differ modestly. The importance of patient selection has been a recurrent lesson from initial negative studies with both mepolizumab and reslizumab. These early trials did not require eosinophilia for entry. Subsequent studies have suggested that eosinophil counts <150 cells/μL are a predictor of reduced efficacy with incremental increases in both eosinophil count and prior number of exacerbations being associated with a greater response.6

Mepolizumab

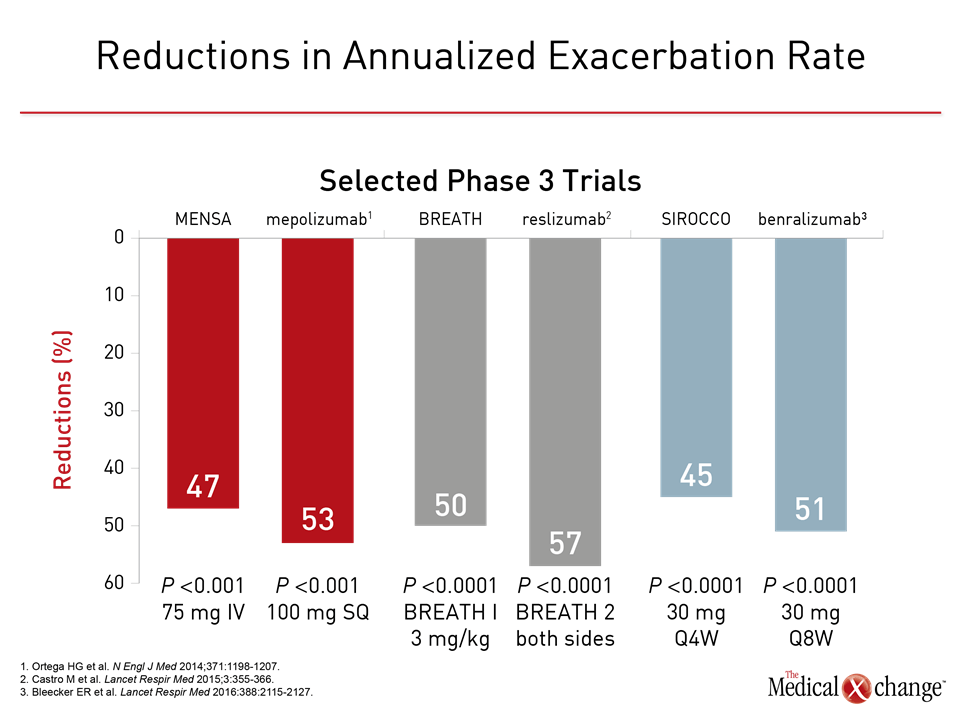

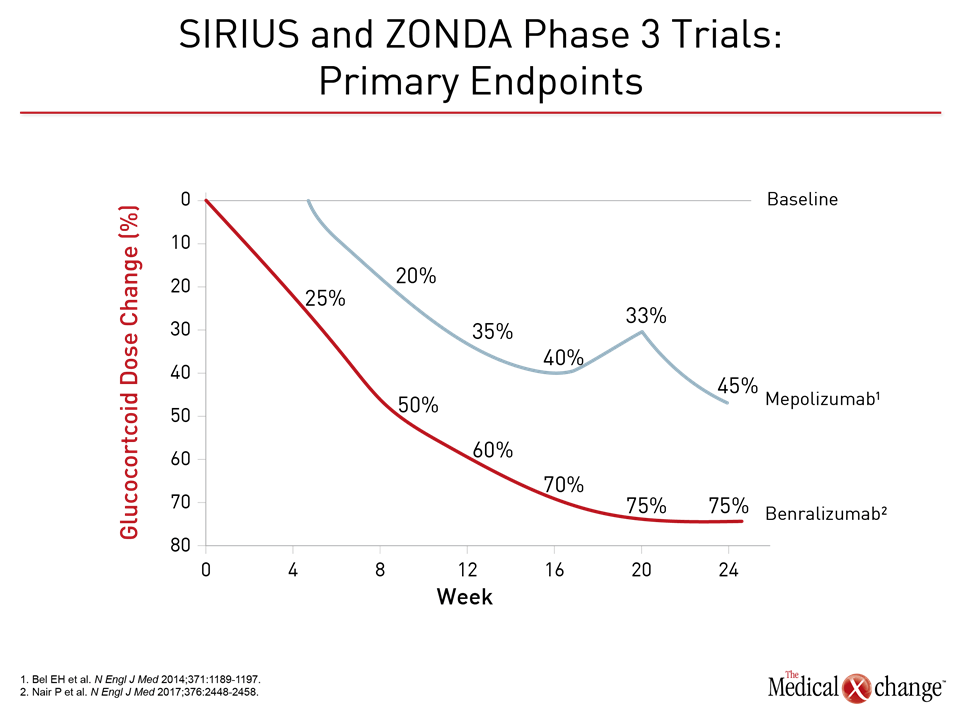

In the first of several phase 3 trials with mepolizumab, called DREAM, 621 patients were randomized to one of three doses of IV mepolizumab or placebo.7 For this study, elevated eosinophil counts in the sputum (>3%) or blood (≥300 cells/μL) were listed among selection criteria but alternative signs of severe asthma, such as a fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration of ≥50 ppb, were permitted. Relative to placebo, the highest and most effective dose of mepolizumab was associated with a more than 50% reduction in the annualized rate of exacerbations (1.15 vs. 2.4; P<0.0001). The efficacy of lower doses relative to placebo was also significant, but the higher dose provided greater efficacy, and all doses were associated with a placebo-like safety profile. Two subsequent phase 3 studies, called MENSA and SIRIUS, were published simultaneously. In MENSA, the primary outcome was change in the rate of exacerbations.6 In SIRIUS , the primary outcome was degree of reduction in glucocorticoid dose.8 Both studies required eosinophilia, defined as a blood eosinophil count ≥300 cells/mcL within the past year or ≥150 cells/mcL at the time of screening, for entry. Other entry criteria included positive results on a methacholine or mannitol challenge during the previous year. In SIRIUS, the two study arms were 100 mg mepolizumab or placebo administered SQ every 4 weeks. In MENSA, a third arm of 75 mg mepolizumab IV was included. In MENSA, the rate of exacerbations was reduced 47% on the 75 mg IV dose and 53% by the 100 mg SQ dose (both P<0.001) relative to placebo over 32 weeks of follow-up. Several measures of lung function, such as the mean increase in FEV1 from baseline were also significant relative to placebo. Active therapy was also associated with improvement from baseline in validated symptom questionnaires, such as the 5-item Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ-5). In SIRIUS, there was a median 50% reduction in glucocorticoid dose in patients treated with SQ mepolizumab but no change on placebo (P=0.007). There was also a significant reduction in the annualized rate of exacerbations for mepolizumab relative to placebo (1.44 vs. 2.12; P=0.04). Symptom improvement on the ACQ-5 that was similar to that seen in the MENSA study. Mepolizumab was also associated with significant improvement with the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). Based largely on these trial data, mepolizumab has been licensed in Canada in a SQ 100 mg formulation for administration every 4 weeks. The indication is for add-on maintenance treatment in adults with eosinophilic asthma, defined as a blood eosinophil count ≥150 cells/mcL at the time of treatment initiation or ≥300 cells/mcL within the past year. In addition, patients should be inadequately controlled with high-dose ICS plus an additional controller, such as a long-acting beta agonist (LABA).

Reslizumab

The clinical development trajectory of reslizumab was similar to that of mepolizumab. An initial placebo-controlled pilot study that did not require eosinophilia for entry was negative.9 A subsequent study that did include a minimal level of eosinophils was associated with clinical benefits, providing the rationale for the phase 3 trials that followed.10 In the duplicate placebo-controlled trials in the phase 3 reslizumab BREATH program published together.11 Entry was restricted to patients with severe inadequately controlled asthma with ≥400 eosinophils/mcL. Reslizumab was administered IV in a weight-based dose of 3.0 mg/kg every 4 weeks. The reduction in frequency of annualized rate of exacerbations for reslizumab relative to placebo was 50% in one study and 59% (both P<0.001) in the other. This agent, like mepolizumab, was described as having a placebo-like safety profile. Based largely on these trial data, reslizumab has been licensed in Canada in an IV 100 mg formulation for administration every 4 weeks. Like mepolizumab, the indication is for add-on maintenance treatment in adults with eosinophilic asthma who are inadequately controlled with high-dose ICS plus an additional controller, such as a LABA. Reflecting the phase 3 trials, eosinophilia in the labeling of reslizumab, unlike that of mepolizumab, is defined as ≥400 eosinophils/mcL at the time of treatment initiation. The FDA labeling for reslizumab is accompanied by an advisory to monitor patients for hypersensitivity and life-threatening anaphylactic reactions. As yet, there is no evidence of a steroid-sparing effect from reslizumab.

Benralizumab

Three phase 3 trials have been conducted with benralizumab, which binds to the IL5Rα to produce rapid depletion of eosinophils through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).12 In the phase 1 studies, a single IV dose of benralizumab, which has a mean half-life of more than 2 weeks, produced rapid and near complete depletion of eosinophils.13 Favorable efficacy and safety with benralizumab in phase 2 trials of a SQ formulation provided a basis for subsequent phase 3 studies.14,15 In two, SIROCCO and CALIMA, patients with severe, poorly controlled asthma defined by numerous clinical criteria, such as ≥2 exacerbations in the last year while on high dose ICS and usually at least one additional controller medication, were randomized to 30 mg benralizumab SQ every 4 weeks (Q4), 30 mg benralizumab SQ every 8 weeks (Q8), or placebo. Expressed as a rate ratio, benralizumab in the Q4 and Q8 regimens reduced exacerbation by 45% and 51%, respectively (both P<0.001) relative to placebo over 48 weeks of follow-up.16 In CALIMA, these rate ratios for the Q4 and Q8 regimens relative to placebo corresponded to 36% (P=0.0018) and 28% (P=0.0188) reductions in exacerbations, respectively.17 In the more recently completed ZONDA trial, which required a blood eosinophil count of ≥150 cells/mcL,18 patients were again randomized to 30 mg benralizumab in a Q4 or Q8 regimen or placebo. On the primary outcome, benralizumab was associated with a 75% reduction in glucocorticoid dose from baseline to week 28, which was significantly greater (P<0.001) than the 25% reduction in the placebo group. The annualized rate of exacerbations was reduced 55% (P=0.003) in the Q4 benralizumab group and 70% (P<0.001) in the Q8 group relative to placebo. Benralizumab has also been associated with a placebo-like adverse event rate. There are no large randomized trials comparing mepolizumab to reslizumab, which are the only therapies currently approved for inhibition of the IL-5 pathway in asthma, but these agents and the experimental benralizumab have different characteristics that may be clinically relevant (Table 1). The phase 3 trials have employed variable entry criteria and dosing strategies, but all have been associated with substantial reductions in the annualized rate of exacerbations (Fig. 2). In the SIRIUS phase 3 trial with mepolizumab and the ZONDA phase 3 trial with benralizumab, both achieved significant benefit for the primary endpoint was the effect on treatment for glucocorticosteroid sparing (Fig. 3).

Practical Approach to Anti-IL-5 Therapies

As demonstrated in the phase 3 trials, inhibitors of the IL-5 pathway are associated with clinical benefit as an add-on therapy in adult patients with eosinophilic asthma who are not adequately controlled on ICS plus an additional controller. For the types of patients included in the clinical trials and on which the current indications are based, these therapies can be an important option for improved outcomes. Due to cost and the need for serial IV or SQ administration, it is essential to use these agents judiciously. Biologics for severe asthma now include the anti-IL-5 MAbs as well as omalizumab, a MAb that binds to IgE. Before employing any of these targeted therapies, it is important to first determine that standard therapies are not offering adequate relief. The multiple reasons for an inadequate response include failure to fill or use prescriptions appropriately. For example, inhaler technique, which remains a common cause of treatment failure,19 should be evaluated routinely. Patients should also be evaluated and treated for comorbidities that mimic or exacerbate symptoms, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), sinusitis, and obstructive sleep apnea.20 Fewer than 10% of patients with asthma have a severe form as defined by poor control on appropriately employed standard therapies.21 The proportion of those with severe disease in which eosinophils are a targetable factor for disease control appears to be even smaller. According to current labeling, eosinophilia is a prerequisite for initiating anti-IL-5 biologics, but additional criteria designed to ration health resources and maximize cost efficacy of these agents are likely to be required regionally in Canada. At the present time, patients with asthma who are sufficiently poorly controlled in the primary setting to require biologics are probably best referred to specialists who can consider these treatments in the context of other options for challenging cases. Many aspects of care, including how long patients should remain on biologics once initiated, remain incompletely understood on the basis of available evidence.

Conclusion

Targeted anti-IL-5 therapies are an effective clinical tool in selected patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. The reduced rates of exacerbation associated with these agents in phase 3 trials have addressed an unmet need in a population poorly responsive to traditional therapies. Efforts to further develop targeted agents and expand personalized therapy are likely to further improve care and broaden the understanding of how eosinophils and other inflammatory mediators participate in the expression of asthma phenotypes.

References

- Bousquet J, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1033-9.

- Chlumsky J, Striz I, Terl M, Vondracek J. Strategy aimed at reduction of sputum eosinophils decreases exacerbation rate in patients with asthma. J Int Med Res 2006;34:129-39.

- Jayaram L, Pizzichini MM, Cook RJ, et al. Determining asthma treatment by monitoring sputum cell counts: effect on exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2006;27:483-94.

- Shalit M, Sekhsaria S, Malech HL. Modulation of growth and differentiation of eosinophils from human peripheral blood CD34+ cells by IL5 and other growth factors. Cell Immunol 1995;160:50-7.

- Nixon J, Newbold P, Mustelin T, Anderson GP, Kolbeck R. Monoclonal antibody therapy for the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with eosinophilic inflammation. Pharmacol Ther 2017;169:57-77.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1198-207.

- Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:651-9.

- Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1189-97.

- Kips JC, O’Connor BJ, Langley SJ, et al. Effect of SCH55700, a humanized anti-human interleukin-5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1655-9.

- Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:1125-32.

- Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:355-66.

- Ghazi A, Trikha A, Calhoun WJ. Benralizumab–a humanized mAb to IL-5Ralpha with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity–a novel approach for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2012;12:113-8.

- Busse WW, Katial R, Gossage D, et al. Safety profile, pharmacokinetics, and biologic activity of MEDI-563, an anti-IL-5 receptor alpha antibody, in a phase I study of subjects with mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:1237-44 e2.

- Castro M, Wenzel SE, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin 5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: a phase 2b randomised dose-ranging study. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:879-90.

- Laviolette M, Gossage DL, Gauvreau G, et al. Effects of benralizumab on airway eosinophils in asthmatic patients with sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:1086-96 e5.

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2115-27.

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2128-41.

- Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med 2017.

- Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement T. Systematic Review of Errors in Inhaler Use: Has Patient Technique Improved Over Time? Chest 2016;150:394-406.

- Boulet LP, Boulay ME. Asthma-related comorbidities. Expert Rev Respir Med 2011;5:377-93.

- Custovic A, Johnston SL, Pavord I, et al. EAACI position statement on asthma exacerbations and severe asthma. Allergy 2013;68:1520-31.

Chapter 4: Anti-IL-5 Therapy and Other Biologics in Severe Asthma

Monoclonal antibodies targeted at the interleukin-5 (IL-5) pathway have been associated with benefit in severe eosinophilic asthma suboptimally responsive to optimized inhaled therapy, such as corticosteroids plus a long-acting beta agonist. The inhibition of IL-5 has helped establish eosinophils, which mature and proliferate in response to the IL-5 cytokine, as a targetable mediator of airway inflammation. An evaluation of the rationale, design, and outcomes of the clinical trials with IL-5 inhibitors informs current indications, but their role may evolve on the basis of studies designed to address unanswered questions, such as the relative importance of eosinophil depletion. Differences in anti-IL-5 therapies, including their mechanism, may be clinically relevant and contribute to a more thorough understanding of how these therapies control airway inflammation. Although biologics have been relatively well tolerated even when administered over extended periods, patient selection and individualized care are essential to their application in cost-effective treatment.

Show review